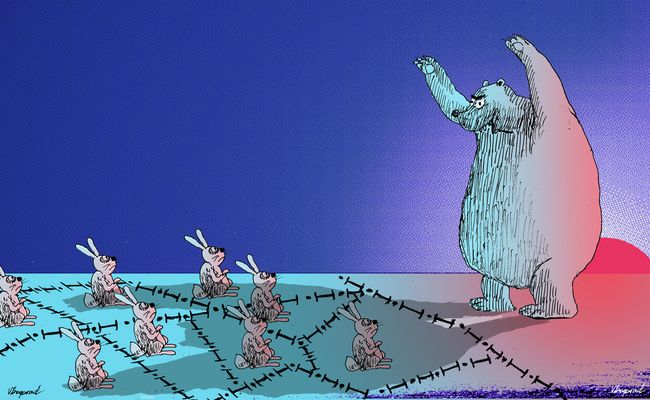

Can Russia be “re-educated”?

Galia ACKERMAN: “The only policy which the Kremlin understands is the policy of force”

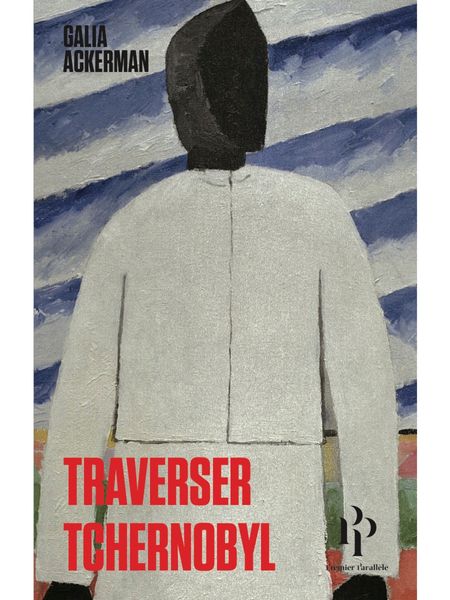

The famous French writer, Soviet dissident, historian, and journalist Galia Ackerman has put a great effort into ensuring that the Western public has unbiased view of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, including its information component. Lately, she was on a brief visit to Ukraine. This time, she came to present her new book Crossing Chernobyl. Ackerman has researched the Chornobyl story for many years. Her studies center on anthropological and philosophical problems which have attained greater relevance due to the disaster. The new book, the general level of education in the West as a political challenge and the historical background of the modern Russian identity – all these issues are covered in Ackerman’s interview with The Day.

Crossing Chornobyl is your third work on this subject. How is it special and different from the first two?

“The Chornobyl theme is inexhaustible. From a symbolic standpoint, this is one of the most important events of the 20th century. I first turned to this theme in 1998, it was almost an accident. I was asked then to translate Svetlana Alexievich’s book Chernobyl Prayer. I grew interested in it, met many well-informed people. In particular, I met Ukrainian journalist Alla Yaroshynska: it was largely thanks to her efforts that the secret protocols of the Politburo became known to the people. I also met outstanding Belarusian nuclear energy scientist Vassili Nesterenko, who dedicated his life to helping the affected population. I talked to Ukrainian academician Dmytro Hrodzynsky, who headed the National Commission for Radiation Protection of Ukrainian Population for many years. Both scientists had suffered heavily from radiation. I also managed to talk with some political leaders, including Mikhail Gorbachev.

“In 2003, I was invited to be the curator of a large Chornobyl-themed exhibition at the Center for Contemporary Culture in Barcelona. I spent three years gathering documents and testimonies. The exhibition covered the period of construction of the power plant, the accident itself and its consequences, the fate of the displaced people and those who remained in the area. I managed to collect a huge collection, and the exhibition covered 1,200 square meters. It was then that I wrote the first two books. One of them, called Chernobyl: The Return of Disaster, used all the data and interviews I had obtained by then. Also, I compiled a large catalog of the exhibition. Meanwhile, the book The Silence of Chernobyl was co-authored by me and two sociologists, Guillaume Grandazzi and Frederick Lemarchand. It deals with intellectual aspects of the Chornobyl disaster.

“When you get immersed in the subject so deeply, when you establish close links with dozens and hundreds of people and even begin to feel a responsibility for them, it is impossible to quit. In 2009, I managed to get permission to spend a whole week in Chornobyl. It then occurred to me to write a book about today’s life in the exclusion zone. I interviewed many people, but the writing effort stalled, since I had to find a style and a structure for it. My work progressed rather slowly. I think that Crossing Chernobyl is special in that it represents the author’s vision. My first chapter tells the story of the city of Prypiat and the closed military town of Chornobyl-2, located near the Duga radar station. Another chapter is devoted to the ancient Ukrainian town of Chornobyl, whose history in a sense reflects the history of Ukraine. A separate large chapter describes the worthy and dedicated people who work in the zone. The book also contains the story of my acquaintance who called himself the boss of the zone. He was a mafioso who was involved in the illegal export of metal. We spent several hours with him, picnicking on the banks of the Prypiat River.

“While working on the book, I met ethnographer and director of the State Research Center for Protection of Cultural Heritage from Manmade Disasters Rostyslav Omeliashko, who had led expeditions to Chornobyl for many years. I asked to go with him so as to see a large collection of cultural artifacts which they were able to gather in abandoned homes and kept in Chornobyl. He then asked: ‘Maybe we can take Lina Kostenko with us as well, cannot we?’ We went to Chornobyl for a day and made a detour to Bolotnia, where Maria Prymachenko’s son Fedir was still alive. As a result, I became friends with Kostenko. By the way, her daughter, writer and culture expert Oxana Pachlowska, read and approved my book. For many years, I have observed the heroic work of Kostenko and Omeliashko, aimed at saving what they call the Ukrainian Atlantis. Every time I come to Ukraine, Kostenko still invites me to visit.”

“THE LINEAR TIME CONCEPT DOES NOT STAND THE TEST OF CHORNOBYL”

The Chornobyl disaster raises many universal problems. In the global context, they include, for example, the question of the relationship between humanity and technology. For the Ukrainian society, Chornobyl is important in terms of understanding the Soviet past, our relationship to it. When thinking on this scale, what aspects of the Chornobyl disaster do we have yet to comprehend?

“The Chornobyl disaster is different from natural disasters, although the latter often have far more victims. However, as time passes, they are gradually forgotten. Why Chornobyl has not been forgotten? In my view, primarily because after the disaster, at least part of this area is fundamentally unrecoverable. The city of Prypiat will never be inhabited again because it is infected with particles of plutonium, whose half-life is at least 24,000 years. Buildings are almost intact, but life has left the city once and for all. Understanding this makes for a fundamentally new situation for humanity. We have freed the forces, I mean transuranic elements, whose lifetimes are incommensurate with human life.

“The nature of time in Chornobyl is strange, nonlinear. In these places, called the Polissia, peasants lived for centuries to the rhythm of changing seasons, and every year resembled the previous one. Suddenly, they found themselves faced with ultra-modern nuclear power. After all, before the construction of the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant, there was not even power connection there, so these people effectively lived deep in the Middle Ages. Then the explosion happened. It lasted just a second and a half, but the aftereffects will linger for tens of thousands of years! Peasants who lived there found themselves in the Middle Ages again, with all the work performed with plow and shovel and no running water. There is another well-known phenomenon as well. Children and young people who experienced long-term accumulation of low doses of radiation suffer from premature, unnatural aging. It turns out that our linear time concept does not stand the test of Chornobyl. That is, we have a philosophical problem here.

“The Chornobyl area, the current 30-kilometer zone, was a kind of a small state-within-the-state during the Soviet era with all preconditions for economic development. Next to Chornobyl, a city that boasted a thousand years of history, they built the ultra-modern Prypiat. The area had agriculture (dozens of villages), shipping (riverine vessels sailed from Belarus to the Black Sea), trade, crafts, industry, a recreation zone with spa climate – it was a thriving piece of land. What is left of it? Agreed, there were not that many dead bodies, but the land has been turned into the biggest nuclear dump in the world. The population that lives there, not including the elderly and squatter returnees, is on a drive-in drive-out schedule, that is, they spend slightly more than half of their time in the area. But it is not productive work, since they do not grow grain or make clothes. The sole purpose of these people is to protect us from radiation that is concentrated there. As a model of a possible future of humanity, it is a terrible example.”

“EUROPEANS ARE GRADUALLY COMING TO REALIZE THAT RUSSIA HAS CREATED A NETWORK OF AGENTS OF INFLUENCE”

Many experts say that currently, Russia’s chief export is corruption. Special operations, bribery, systematic funding of marginal parties in Europe (often diametrically opposed on ideological allegiance) – all these are tools which Russia keeps using. What do you think, have the European public and elites learned to respond adequately to these challenges?

“The Europeans are gradually coming to realize that Russia has established a network of agents of influence. For example, French scholar and analyst Cecile Vaissie recently published an interesting book on such networks in France. It lists many important facts and describes specific mechanisms. In particular, they use the old Russian emigration, whose members believe in the revival of the ‘millennial Russia,’ not realizing that it is actually a KGB production. Many people in the right and far-right circles, as well as some representatives of the far-left opposition in France, influenced by their hatred and rejection of America and due to special French ‘sovereignism,’ support Russia in the mistaken belief that together with Russia, France will be able to go ahead without the EU and America. This, of course, is a mirage and a fiction, which, however, is very skillfully supported. Unfortunately, such sentiments exist in the French military as well. How will these trends affect the parliamentary and presidential elections is yet to be seen, but they definitely do exist. For example, the Russian and French governments have lately announced the Cross-Cultural Tourism Year, to be held in 2016-17. Other similar projects were implemented in previous years. Both houses of the French parliament include members who openly support Russia and oppose sanctions. These people are there, and today we are starting to publicly name them at least.”

“JUST SCREAMING IS NOT ENOUGH, AS YOU NEED TO BE LISTENED TO AS WELL”

Do the results of the referendum in the Netherlands testify to the effectiveness of such a strategy?

“In my opinion, this is primarily a Dutch problem, because each country has a different ratio between the right, far-right, left, liberals and others. It so happened that the far-right have for many years had a very strong position in the Netherlands. As you know, out of 32 percent who took part in the referendum, more than 61 percent voted against the Association Agreement between the EU and Ukraine, but in absolute terms it was less than 20 percent of the Dutch. What the remaining 80 percent really think is not very clear. Each country develops in its own way in relation to the context of European integration, and the Netherlands, as well as some other countries, is quite unfavorable in this regard. The ‘No’ voters came primarily from the Euroskeptic electorate, and I think that most of these people know little about Ukraine.”

Unfortunately, the same can probably be said of many EU citizens. The idea of special historical closeness of Russia and Ukraine is still popular in the West, even though if you look at the facts, Ukraine has much more in common with Lithuania or Bulgaria. Twenty-five years ago, this “myopia” was understandable, but now... It cannot be explained solely by impotence of Ukraine’s information policy. The blame should be shared, perhaps, by an internal European problem, I mean the problem of education?

“If I was to grade the European public’s knowledge of history, I would have graded it ‘D’ at best. One can see this for oneself by looking at the TV show Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? People know about popular artists or TV anchors, but if you ask them about the capital of Portugal, never mind Ukraine, most find it difficult to answer. Or, say, classical literature: people get asked who wrote Madame Bovary, and options are Honore de Balzac, Gustave Flaubert, Guy de Maupassant, and Marcel Proust. It seems an elementary question, but no, people cannot solve it without calling a friend. The general level of culture, unfortunately, is quite low. Is it any wonder, then, that regarding Ukraine, the average European is able to repeat only one or two commonplace cliches. When watching the main French news channels, I am stunned to see how much they are fixated on France. Our national TV will rather talk about a minor incident in the French countryside, while the momentous events in the outer world go not mentioned at all or mentioned in passing. In addition, Ukraine suffers from its anti-Semitic image, established during the Soviet era, and this topic is still very skillfully exploited. They say that Ukrainians exterminated Jews and were accomplices of the Nazis. Of course, there were accomplices of the Nazis here, but, unfortunately, it happened everywhere. Why, then, is this still hanging over the Ukrainians instead of the Lithuanians, Belarusians, Croats, Norwegians...”

The Russians!

“Yes, the Russians, who, incidentally, had an entire Russian Liberation Army, fighting for the Nazis under the command of Andrei Vlasov! It is because this image has been cultivated since the immediate post-war years, when the Ukrainians strongly resisted the Soviet regime. Even Alexander Solzhenitsyn in his book The Gulag Archipelago described the Ukrainian nationalism as a major force. For the Soviet regime, spreading the anti-Semitic myth was a way of discrediting this force. Of course, the information policy of Ukraine could have been more active, but just screaming is not enough, as you need to be listened to as well, and this is very difficult to achieve.”

“THE SECOND WORLD WAR IS THE SACRAL BASIS OF TODAY’S RUSSIA”

Soviet ideology, Stalinism, autocracy, Orthodoxy – the modern Russian identity consists of many seemingly disparate fragments. How is this possible?

“I think the main fragment of the Russian identity is the imperial idea. Over the past few centuries, the very notion of Russia was equated with the territorial expansion. Continuous expansion was seen not as a conquest, but as a ‘natural’ process that occurs under conditions of pseudo-love. ‘The Third Rome,’ ‘the light from the East’ – this messianic idea postulated that the whole world must be conquered by the Russian soul. In the name of this objective, the Russians embarked on colonization efforts and became servants of the empire, and were then deliberately sent to all parts of the country to become its ‘cementing’ element and – collectively, as a people – ‘the sovereign’s watchful eye.’

“In the aftermath of the First World War, two land-based empires built on the principle of territorial expansion collapsed, I mean the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian ones. How, then, the Russian Empire managed to survive, recreated in the form of the Soviet Union? Of course, Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin had to give up on some imperial principles, which enabled a brief national revival in some republics, which saw formal independence, the emphasis on the national languages, and the cultures which were national in form and socialist in content. But Stalin quickly realized that it was dangerous and bound to activate centrifugal movements. Already in the 1930s, the idea of the Russians as the ‘cementing’ people made a comeback.

“Internationalism, ‘bright future,’ Communism – the empire had supposedly new ideology now, but even though the rhetoric was different, the essence remained the same: the imperial idea with potential for further expansion. It was painfully confirmed after the Second World War, when half of Europe was put under direct Soviet control, despite the fact that these countries retained nominal independence. In addition, Stalin directly attached a number of areas to the USSR, sometimes even going beyond the borders of the Tsarist empire.

“For centuries, the people were educated in the imperial mindset, that of a great power which is enlightening the world (with spiritual light under the Tsars and with that of the Communist ideology under the Soviets). But if we see territorial expansion as the most essential feature of empire, its specific justification is not that important. That is why the third stage is possible, when after Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin, we are again seeing a return to the overtly imperial idea. It was possible to reconcile the seemingly irreconcilable poles of the Tsarist Russia and the Soviet Union. They were two avatars of the empire, and now we have to deal with the third one. Repugnant as it is, I sometimes watch Russian TV broadcasts and very clearly see them promoting the old idea that Russia is bringing goodness and light to the world (though it is not very clear what these goodness and light are).

“Another justification is the Second World War. ‘We won the war, destroyed the worst evil ever which was Adolf Hitler, therefore we are a force for the good, and everything we do is justified. As victors, we are entitled to everything.’ The logic is very primitive, but in the presence of stereotypes of imperial consciousness which are already genetically entrenched, it works. After the de-Christianization implemented by the Soviet regime, purely Christian ideas are unworkable in contemporary Russia. You cannot rely on the Communist ideas either, because they were defeated. What is left? A new sacred idea that of the Second World War as the sacral basis of today’s Russia.”

Do you think that the European political and intellectual elites understand that the foreign policy of contemporary Russia and the nature of the regime that exists there is not only the deed of the KGB gang or a result of propaganda, but also a response to the deeply-held aspirations of the Russian people?

“I think they do not realize it fully. Conventional political rhetoric on Russia is that, despite everything, it is a ‘great nation’ with a great culture. They say the Russians were humiliated, and now that Russia has ‘risen from its knees,’ we should allow it some time to change. That is, common understanding of the issue is rather primitive. There are very few deep thinkers in the world who understand the nature of contemporary Russia. One of them is famous French scholar, historian, and political scientist Alain Besancon.”

“WE NEED A REVOLUTION ‘FROM ABOVE’ AND THE NEW MODERNIZATION OF THE RUSSIAN SOCIETY”

Is it possible at all, in your opinion, to implement a democratic state project in Russia, and how the civilized world can contribute to its implementation?

“The past 15 years have seen a terrible dumbing-down of Russian people. Vladimir Putin’s regime is very populist. It relies on the masses rather than on the civilized elites. By the way, Russia does have these latter, making up those 15 percent of the population, that part of the middle class, which opposes the regime and which is recognized as existing by the Russian authorities themselves. I think that escaping from this situation and moving to a democratic regime is virtually impossible at the moment. The only way to do it is through a new revolution ‘from above,’ a revolt of the elites who would succeed in coming to power and imposing on the society a new modernization and democratization. In recent Russian history, there were two such attempts. The first one was Gorbachev’s revolution ‘from above’ of glasnost and perestroika, which was based on intellectuals, the so-called Sixtiers, and was supported by the Komsomol and ethnic elites (each had their own reasons for it). The second one was the Yeltsin administration, which also relied on the elites, but these were not democratic but rather the new business elites, the extremely liberal forces. Neither the first nor the second trend enjoyed wide popular support. Neither Gorbachev nor Yeltsin managed to ‘re-educate’ the people, to change its mentality. What you need to succeed with it and how long it will take, I have absolutely no clue.

“The only policy which Russia understands is the policy of force and deterrence. In this sense, sanctions are a very effective tool. We should not have true friendship and cooperation with a Russia which openly declares anti-Western values, because it is perceived only as a sign of weakness. History shows that the US-USSR confrontation was the right way to do things. Then, at least, there were clear rules, while now there are none at all. Today we have a ‘multipolar world.’ Accordingly, Russia is playing on the contradictions between Western nations. In my opinion, the sanctions, unfortunately, are unlikely to last for long. The fact that they have held so far is already a miracle. We will see ‘maneuvering,’ attempts to pit different interests against each other, as Russia will continue to adhere to the principle of ‘divide and rule.’ The correct answer to this challenge can only be the complete unity of the Western world, but I am not sure that this is possible today.”

The Day’s FACT FILE

Galia Ackerman is a writer, historian, journalist, translator, Doctor of Religion Studies of the Pantheon-Sorbonne University, co-founder and secretary general of the European Forum for Ukraine. She worked for Radio France Internationale, Huffington Post, Le Monde, Liberation, Courrier de l’UNESCO, Histoire et Liberte, La Regle du Jeu, Politique Internationale, Novaya Gazeta and other publications. Ackerman is an expert on totalitarianism and Soviet history. In the spring of 2015, she compiled a Ukraine-themed issue of La Regle du Jeu, entitled Ukraine: the Terra Incognita of Europe.

Newspaper output №:

№29, (2016)Section

Society