The history of a revolution

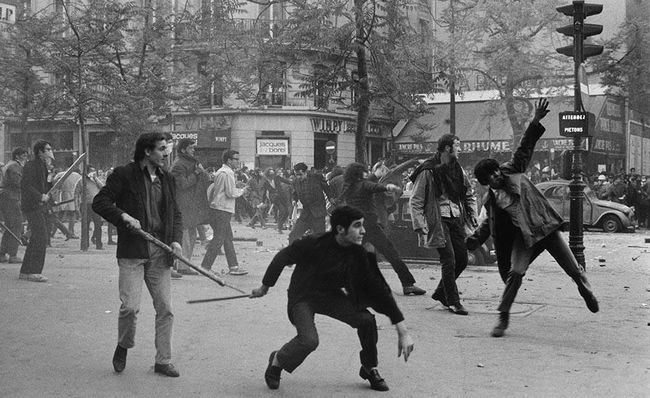

Half a century ago Paris saw the events that went down in history as “Red May”

The 50th anniversary of “Red May” is receiving wide coverage in France and the rest of the world. This article focuses not so much on 1968 itself as on the book and the film that influenced the course of that strange revolution.

First, about The Society of the Spectacle by Guy Debord and Situationism.

Situationism has its roots in Letterism founded in 1946, which in turn developed the ideas of Dadaism, a rebellious art movement in 1910-20 (in particular, poets Andre Breton, Paul Eluard, Tristan Tzara, and our great sculptor Oleksandr Arkhypenko used to be Dadaists). After a number of scandals, Letterists, together with like-minded people in Europe and America, formed the Situationist International (SI) in 1957. The new organization was led by Guy Louis Debord (1931-94), a “writer, strategic thinker, and adventurer” (in his own words), the author of seven books and six films. He wrote the basic Situationist work – The Society of the Spectacle.

“The spectacle is the ruling order’s nonstop discourse about itself, its never-ending monolog of self-praise, its self-portrait at the stage of totalitarian domination of all aspects of life. The fetishistic appearance of pure objectivity in spectacular relations conceals their true character as relations between people and between classes: a second Nature, with its own inescapable laws, seems to dominate our environment. But the spectacle is not the inevitable consequence of some supposedly natural technological development. On the contrary, the society of the spectacle is a form that chooses its own technological content… The spectacle is not a collection of images; it is a social relation between people that is mediated by images.”

The spectacle causes estrangement of workers from the products of work and of people from their own reflections. The image becomes the product of consumption, as much estranged as everything else. Reality is superseded with the spectacle which is no longer an entertainment, for it has merged with a society in which the media have replaced the language, memory, and communication: people “grope for life.” The spectacle is “the main production of contemporary society.” At the same time, he socially atomizes people and then unites them into a society of obedient individuals, while the further development of mass-scale cultural production results in an inferior quality of products and impossibility to sell really valuable things. In Debord’s view, this state of affairs is also typical of the socialist camp which is under the power of a “concentrated spectacle.”

Incidentally, Debord’s followers took a good dose of anti-Soviet vaccine: one of the first documents of the rebellious Sorbonne students was a telegram to the CPSU Central Committee: “Long live the struggle of Kronstadt sailors and Makhno’s anarchists against Trotsky and Lenin! Long live the uprising of Budapest Councils in 1956! Down with the state! Long live revolutionary Marxism! Occupational Committee of the Autonomous People’s Sorbonne.” The events in Paris contradicted the Soviet ideology. Moreover, they indirectly posed a threat to the whole system, for they triggered student revolts also in Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia – the young people of these countries were inspired by the staunchness of their French peers.

Situationists believed that a revolt of the minority would lay the groundwork for the liberation of the majority. To counter the Spectacle, they called for thinking with brains, not with television. As a matter of fact, they called themselves situationists because they devised the tactics of “constructing situations” in order to replace “the audience” and “actors” of the Spectacle with “people of life” for the sake of joint participation in the production of images via a spontaneous revolt, direct actions, and scornful games with publicity cliches in political campaigning. In 1966, after taking the lead in Strasbourg University’s student committee, Debord’s followers printed 10,000 copies of the pamphlet On the Poverty of Student Life by situationist Mustapha Khayati. Branded by a French court as “dirty” and “antisocial” and translated into all European languages, the book became a practical guide for radical students. Two years later, in early May 1968, SI activists at the Sorbonne’s branch in the Parisian suburb of Nanterre provoked disturbances which soon engulfed the capital and the whole France. It has been written very much about what happened next. As for Situationists, outright anti-capitalism and anti-Sovietism prevented them from seeking a compromise. SI was disbanded in 1972. In Comments on the Society of the Spectacle (1989), Debord stated the global domination of an “integrated” Spectacle which absorbed both the concentrated and deconcentrated Spectacles (USSR and USA, respectively).

Now it is worthwhile to speak of the work that supplemented Debord’s ideas in a paradoxical, art-related, way.

This summer Paris movie theaters are going to abound in the billboards of retrospectives devoted to May 1968. Jean-Luc Godard’s Weekend will be a must-see. This film, which appeared in 1967, as did The Society of the Spectacle, also had a strong impact on what happened in Paris the next year. Godard was a founder of the French “new wave” in cinema – his debut, Breathless (1960), starring a young Jean-Paul Belmondo, changed the world cinema.

At first, Weekend looks like an embodiment of absurdity. Corinne and Roland, a middle-class Parisian couple, set out by car for Corinne’s parents’ home in the countryside to secure her inheritance at any cost. They finally fall into the hands of the Seine and Oise Liberation Front. The insurgents feed off what they find on the roads, including tourists. Their new captives are no better, for they killed the old woman and seized the desired millions. In the end, Corinne sides with the guerillas and eats, together with them, her husband’s liver for supper. But it is not a horror film but a very black satire, the author’s message hidden behind tawdry absurdities.

Weekend’s roads are in a terrible mess: cars and people are mixed all the way; all are extremely angry, beat and destroy one another. The chaos of highways is shown against the backdrop of landscapes of the fringe and encounters with some bizarre creatures. The first and most chimerical of them is Joseph Balsamo in the episode “Exterminating Angel,” a guy with a red cloak and a black cap on, who fires uninterruptedly but never kills anybody with a pistol, along with his decoy girlfriend. He is “God and the son of God,” and… Alexandre Dumas. He is here “to inform these Modern Times of the Grammatical Era’s end and the beginning of Flamboyance, especially in cinema.”

After the title “The French revolution at the weekends of the National Revolutionary Union,” a young man looking like Saint-Just livens up a bucolic landscape with invectives about freedom, slavery, and social contract.

Roland and Corrine are trying, unsuccessfully, to rob a youth, who sings a serenade in a telephone booth, of his car.

In “The Lewis Carroll Way” the travelers are driven crazy by an old-fashion-clad couple: Ms. Emily Bronte, who holds a book, and an infantile fatty covered with pieces of paper with fragments of all kinds of texts. They spout quotes and answer any question each time more and more poetically and mysteriously. Roland calls out: “This isn’t a novel, this is a film. A film is life” and burns the girl.

Traveling across the villages with his piano, a Mozart-crazy pianist not so much plays as talks profusely about his idol.

Two garbagemen, who display thorough knowledge of the geopolitical situation, set out Engels’ class theory in detail and have a well-thought-out plan of guerilla warfare in Western countries.

Finally, after the killing of an unyielding mother-in-law, come the Front revolutionaries who seem to be part of a carnival-style conspiracy of hippies, Native Americans, drag queens, and rock stars.

Naturally, these characters are not real people but symbolic figures of culture. Meanwhile, contemporary civilization is presented as a vicious circle of communication lines. Corinne and Roland belong to this civilization – fussy and crazy about speed and consumption. People are maniacally purposeful, they need to know exact distances, directions, and amounts, and they show a list of wishes to Balsamo, having believed in his divine essence, such as a Mercedes, a Saint Laurent dress, a hotel in Miami Beach, becoming a natural blonde, a weekend with James Bond. By contrast, tribes of the cultural fringe are concerned about less practical problems of human origin or the inner life of a roadside stone. In other words, they offer alternatives.

Similar alternatives were also offered in 1968. The political component is important, but a revolution in postwar Europe is, rather, a question of style. A total carnivalization of events, Odeon theater and the Sorbonne as centers of insurgence, and, naturally, the famous slogans – “It is forbidden to forbid,” “Be realistic, demand the impossible,” “Forget everything taught, begin to dream,” “You can’t fall in love with industrial growth,” “The revolution is incredible because it is real,” “All’s good: twice two no longer makes four,” which sound like proclamations of artists rather than a program of taking power and making everyone happy in the same manner. Debord himself reiterated: “We say that it is necessary to multiply poetic objects and subjects, which are unfortunately so rare at present that the most minimal take on an exaggerated affective importance... One has already interpreted the passions: it is now a question of finding others.” Obviously, what was going on was something deeper than just a struggle of classes or political systems. In Godard’s film, culture fights with civilization as with transportation integrity. And the same opposition – culture vs. civilization – was foreseen by the author of The Society of the Spectacle. The year 1968 only manifested this clash with an explosive acuteness.

Ii is futile to find out who won and who failed, for neither the Spectacle nor the alienation that it causes have not disappeared. The politics of the entire post-Soviet space – Ukraine being no exception – is a graphic illustration of “integrated” spectacular wretchedness, while Russia is getting back to a customary totalitarian Spectacle. Society is freezing in the grip of images transmitted on all the possible channels to the glory of a triumphant mediocrity.

The situation is zero.

Newspaper output №:

№28, (2018)Section

Close up