Encounter: Ivan Kavaleridze and Ulas Samchuk

Two takes on the same event

Today the gradual opening of once-closed archives means we can now acquaint ourselves with books that were published abroad. In many cases, our new knowledge does not tally with what we were forced to learn. In some cases, previously unknown information is revealed, which is helping to fill in the missing pages of our history.

Lately, however, there are increasingly louder calls to reject these revelations because they are distorting history, which was allegedly correctly interpreted in the past. Naturally, this opinion has nothing to do with the truth. Here are two takes on the same event that was witnessed by two outstanding figures of Ukrainian culture.

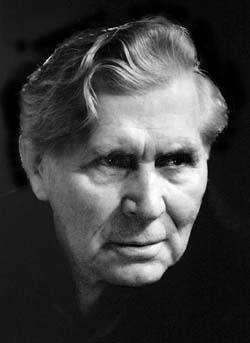

Ivan Kavaleridze was a famous Ukrainian sculptor and film director. In 1941 he was making a movie about the Ukrainian Robin Hood, Oleksa Dovbush. Here are a few fragments from Kavaleridze’s reminiscences about events that took place in 1941, which are cited in the book Ivan Kavaleridze (Mystetstvo Publishers, Kyiv, 1988): “For many years I have kept the business trip permit that led me, by force of circumstances, to pass through all the circles of hell. It reads: ‘This is to certify that film director I. P. Kavaleridze has been sent by the Kyiv Feature Film Studios to Lviv, Stanyslaviv, and their oblasts, in connection with the shooting of the film Song of Dovbush until July 2, 1941.’

“The eight days of shooting were disastrous: the weather was bad, the transport kept breaking down, and we couldn’t find enough extras. The work was not coming together. I had a premonition of some fatal events. On the ninth day, the war broke out.

“There was no communication with Kyiv. The local authorities suggested that those of us who were reservists should head for the nearest draft board, while the rest should try to return to Kyiv.

“There were 27 people left in the film crew. Suitcases, bundles, props. We loaded all this onto a truck and a pickup and set off.

“We quickly passed through Lviv, which the enemy was bombing. Suddenly the highway was deserted, and we shivered with fear.

“Out of the blue some Nazi motorcyclists rode up from a ravine, followed by a heavy tank. The motorcyclists instantly surrounded us. The tank approached slowly, the hatch opened, and a head and a hand holding a pistol appeared.

“Seeing that we were unarmed and not resisting, the Nazis began to ask us who we were and where we were going. We said we were coming back from a filming expedition.

“They ransacked our things and commandeered the trucks and all our belongings. We had to make our way on foot. We spent the night in a barn packed with sheaves of threshed straw.

“We walked for 12 kilometers. There were less than 40 km left to Rivne. From there, it’s just a stone’s throw to Novohrad-Volynsky and Zhytomyr.

“At another road check, a German soldier wants to send us back to the Dubno military police station. He suspects we are intelligence agents.

“The police clerk is carefully scrutinizing our documents. When it comes to my ID, somebody gets a thick encyclopedia published either in Munich or Lviv, and he begins leafing through it. A small note in the encyclopedia about the sculptor and film director Kavaleridze saved our lives.

“Pending permission to move on, we are detained in a hamlet 1.5 km from Dubno: we’ve been weeding a vegetable garden, digging ditches, and tamping a highway.

“When we were allowed to walk to Rivne a month later, we had to sleep in the same barn again.

“We reached Rivne, came to the demolished railway station, groped for a bench in the darkness, and fell asleep. When we woke up in the morning, we saw the huge ceiling of the station hall hanging by just one beam. We rushed out of the hall, saved by a miracle. It started raining and thundering, and the ceiling caved in...

“I go outside and see the highway to Novohrad-Volynsky and then to Zhytomyr and Kyiv.

“Suddenly I see a stranger in front of me. He stares at me and then asks an astonishing question:

‘This is the best place for the monument, isn’t it?’

‘What monument?’

‘I mean Oleko Dundic (a fabled Yugoslav freedom fighter who served in the Red Army and was extolled by Soviet propaganda — Ed.).’

‘I’m not asking who you are, but...’

‘We met once in Kyiv’s culture department.’

“He wrote to me as soon as he came out of the underground. It turned out that my interlocutor was Vasyl Behma, secretary of the Rivne oblast party committee.”

This is the last time that Rivne occurs in Kavaleridze’s memoirs. At this very time the writer Ulas Samchuk was also in Rivne, where he was working as the editor of the Ukrainian newspaper Volyn.

Here is what he wrote about the same event in the book Riding a White Horse (cited from the 1980 edition published by the Volyn Society in Winnipeg, Canada): “That same evening I had a very interesting meeting with a group of people from the Kyiv Film Studios, who had come on the eve of my arrival and settled opposite my temporary lodgings: film director Ivan Petrovych Kavaleridze, his script-girl Tetiana Fedorivna Prakhova, cameraman Ivan Ivanovych Shekker, and his wife Vira Mykhailivna.

“It was a very intriguing group of people indeed: some members of Kavaleridze’s film crew, who were making Song of Dovbush in the Carpathians and then running from the war to Kyiv, were intercepted by the Germans. They had a lot of adventures and now they have come here.

“Our meeting was exceptionally straightforward and pleasant. Incidentally, they had already heard of me by chance from a villager in Pantaliia, near Dubno, in whose house they had stayed for some time. Ivan Kavaleridze, a tall and burly gray- haired man, with a distinctive bony face, occupied a separate small room. We met as though we were old friends. Within a few minutes, we were already talking about a lot of mutually interesting things, such as cinema, literature, and reminiscences. I showered him with questions about Kyiv and various well-known people. He knew a lot about this and was able to recount much.

“I was also intrigued by Kavaleridze himself, one of the pioneers of Ukrainian cinema well before World War I, in the times of the so-called ‘atelier on Surets,’ the second most prominent master of cinematic art (after Alexander Dovzhenko), the creator of such films as Koliivshchyna, Perekop, Zlyva (The Downpour), Shturmovi nochi (Attacks by Night), Natalka-Poltavka, Zaporozhets za Dunaiem (Zaporozhian Cossack beyond the Danube) and many others, as well as an outstanding sculptor, the creator of numerous sculptures. Prakhova, who was first an actress in such films as Dovzhenko’s Earth and Bilynsky’s Transbalt, later became a prominent film editor of films by Dovzhenko, Kavaleridze, Anensky, and Savchenko. She worked on such pictures as Piatyi okean (The Fifth Ocean), Prometheus, Natalka Poltavka, Zaporozhian Cossack beyond the Danube, and Bohdan Khmelnytsky. Ivan Shekker is an outstanding cameraman, a pupil of the famous Dmytro Demutsky, and co-director of many well-known films. Finally, his elegant wife Vira, who worked as a secretary at the film studios.

“For me, their arrival was an exceptionally striking event, because I was thirsting for these kinds of people from Kyiv. I wanted to understand them and learn a lot from them. And I did understand them. We understood each other. We met and became friends — for a long time.

“And that evening there was an exciting reception at Stepan Skrypnyk’s home. Naturally, our Kyiv guests were also invited.

“This first meeting with people from ‘the other world’ was full of very intimate, deep, and sincere feelings, which I would like to express in a special way. Songs, music, dances, and happy laughter are the best language to speak in such cases, so Skrypnyk’s small home was full of this language and an ideally good mood: everybody wanted to have a break from the war, ideology, and gossip, and be a human among humans. I remember Vira Shekker with her Creole-type, coquettishly-smiling, discreetly-alluring, and very feminine face, with her bright amber-colored eyes and unruly auburn hair, and the song “Curly Forelock,” which she sang with such passionate expressiveness and subtle tenderness. Again I can picture Tania Prakhova, Vira’s total opposite: tensely calm, agitated, with wonderful, large, and deep hazel eyes, and a fresh, bright flush on her alabaster cheeks. Wearing a bright red sweater and black satin skirt, she looked like the ideal model for Renoir-style pictures, a blend of the Ukrainian Black-Sea and French-Provencal types.

“Ivan Petrovych Kavaleridze was calm and even-tempered. He did not drink at all but was very sociable and full of good humor, and when we launched into a singing competition, he sang ‘The Black Sea Cossack’ very nicely with his weak, muffled voice, and his interpretation of this song left its imprint on my memory for the rest of my life.

“It was a marvelous evening, there was a lot of talk and laughter, and it lasted until well into the beautiful Ukrainian night. Then we dispersed reluctantly to our homes to the tune of ‘Stay Well,’ which seemed to be Stepan’s favorite Belarusian song.”

Compare these reminiscences by Kavaleridze and Samchuk, two well-known personalities. The fictional meeting with Behma was probably inserted at the demand of the communist who edited the film director’s memoirs. In Soviet times it was forbidden to mention Ukrainian patriots, including Ulas Samchuk. While Kavaleridze’s memoirs describe a terrible night in Rivne’s ruined railway station, in reality there was a warm reception in a hospitable house, with dances, a hearty meal, and a cordial and friendly conversation. Tania Prakhova from Kavaleridze’s film crew remained behind in Rivne and later became Samchuk’s wife. After the war she went overseas with him. Ivan Shekker and his wife Vira also stayed behind to work for the Rivne-based newspaper Volyn. They were also part of Kavaleridze’s crew.

These events should have been reflected in an authentic memoir. Yet there is not a single word about this important event in the life of Kavaleridze. Can our history really do without Samchuk and his friends and acquaintances? The communist editors removed all this from Kavaleridze’s memoirs, and in all probability banned any mention of these “Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists.” Kavaleridze finally left Rivne and returned to Kyiv. How did he describe this event?

“In Nazi-occupied Kyiv I saw deserted streets, the skeletons of demolished buildings, the burnt-out carcasses of the Darnytsia and Novo-Divochyi bridges, and the ruins of the Lavra.

“In the very first days of the occupation of Kyiv, the local intellectuals who had been left behind began to do their best to save our people from slave labor in Germany, preserve cultural values, such as books, paintings, and sculptures, and protect artists’ studios from looting. Attempts were made to keep intact what museum employees had failed to evacuate in time.

“To enable people who were being persecuted by the Germans to leave Kyiv, ‘provincial tours’ were organized. Theater companies consisting of so-called actors — in reality, people from various walks of life — would stage Natalka-Poltavka and Zaporozhian Cossack beyond the Danube. Tickets were exchanged for flour and millet. This helped people to survive and not starve to death.”

When Samchuk arrived in Kyiv, he met Kavaleridze. The film director showed Samchuk around the city and the film studio. But you will not find this in Kavaleridze’s memoirs. Now compare this with how Samchuk looks back on those days in his book Riding a Black Horse, which was released in 1990 by that same Ukrainian Canadian publishing house.

“It is very good that Ivan is a celebrated film director; that’s why his house is appropriately distinguished. Four rooms with a kitchen for just one family is, by Soviet standards, something out of a fantasy.

“Nadia Pylypivna (Kavaleridze’s wife — Ed.) is busy preparing supper. I am laying out what I have brought from Volyn, and in the twinkling of an eye the dining room table is covered with a white cloth and piled with food and drink.

“After visiting the Union of Writers, I intended to drop in at the Kyiv Department of Culture and Arts, at 10 Shevchenko Boulevard, which Ivan Kavaleridze headed at the time.”

In our history books you will never find a single word about this particular job of Kavaleridze’s during the occupation.

Here is another quote from Riding a Black Horse. After seeing the sights of Kyiv, Samchuk and Kavaleridze came home. “We arrived home at about five o’clock. Incidentally, the electric lights came on and the central heating radiators began to work at that very moment.” Who was working at the power plant and the boiler room during the occupation? The residents of Ukraine were. So many times I heard that Ukrainian citizens should not have worked for the Nazis during the occupation. But then who would have baked bread, worked at the power plant and the boiler room, and swept the streets? Ukrainians were doing this. The Germans were not going to do this for the residents of Kyiv: let the slaves die off faster and free up the Lebensraum (living space).

Even more ludicrous is the suggestion that all the people should have joined the partisans. So somebody had to work to be able to survive. At the beginning of the occupation the Germans were not engaged in organizing life in Kyiv. They simply maintained order. This is why Ivan Kavaleridze was the head of a department at Kyiv’s City Hall.

In communist times the Soviet censors expurgated the name of Ulas Samchuk from Kavaleridze’s memoirs, substituting fictional accounts of his contacts with partisans in Rivne. This is the story behind that history.

Harii Makarenko lives in Zhytomyr

Newspaper output №:

№17, (2007)Section

Culture