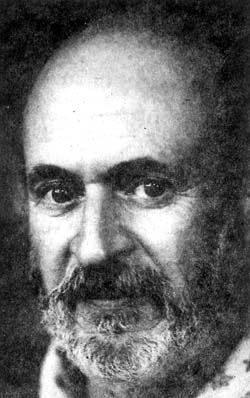

Valery Akopov’s old Kyiv

For many years Valery Akopov, an artist who recorded the image of vanishing Kyiv, was branded as a “slanderer of Soviet reality.” Thirty five years ago Akopov, shocked by the fact that his beloved city was sinking into oblivion, decided to artistically record everything related to Kyiv’s inimitable atmosphere. It took him 15 years to do this. Today Akopov’s works can be found in catalogues of the finest art works dedicated to Kyiv, and he recently starred in Liudmyla Mykhalevych’s documentary film produced for a Ukrainian television channel.

“A PICTURE IS A PRESENTATION OF ETERNITY”

Valery Akopov dreamed of being a geologist, not an artist. He used to buy books on geology and mineralogy and collect rocks. After leaving school, he went to Dnipropetrovsk. But it turned out that he had a heart disease. Goodbye, geology! Valery returned to Kyiv thoroughly disheartened. He tried to find a job but was repeatedly rejected. His mother then said, “You like drawing, don’t you? I have an artist friend. Let’s show her your drawings.” She took her son to the artist’s studio on Andriivsky uzviz.

“I began to visit her every day,” Akopov recalls. “She taught me the way young people were taught in the old days, when there were no institutes. A young person would come to a studio, where the master would first set him to grinding colors into powder and then priming canvases. Then he could start drawing. I went through this kind of ‘school’ with Tetiana Ivanivna. Then she took me to an evening painting class at a studio, where one of her colleagues from the institute worked, so I did an academic course.

“After completing the course, I felt like an artist. I decided not to enroll in the institute: ‘Do they really teach? They will just spoil me. I’ll do it on my own!’ I was 22 at the time. Then I got married and moved to Motovylivka, where I settled down in a small house that belonged to my wife’s parents - wonderful people. Water was three blocks away. I had to take it from a well and carry it home six times a day. I didn’t know where to get firewood and coal. When the roof leaked, I would climb up to fix it. Maybe this saved me — I stopped thinking about my heart. Instead, I thought that I would either become an artist or die.”

You became an artist as well as an essayist. One of your essays has this line: “I think I am a person who is standing at a crossroads. The first road leads to real fame. The second is the path of understanding the unimportance of sham victories and achievements.” Can you explain this?

“The point is that at first I became deeply interested in the avant-garde. I was told in the mid-1960s that I had a radiant future ahead of me. This boosted my spirits, and I became an avant- gardist right down to my fingertips. Then I met an elderly artist. Without trying to win me over, he talked to me at length, and when I looked back three years later, I could not recognize myself. Now I am convinced that the avant-garde is a symbol of destruction because it signals the twilight of a cultural era.”

So you went to the gateways of Kyiv?

“If you’re talking about the ‘Old Kyiv’ series of drawings, then that’s a separate topic. In the 1970s the city began to be built up at a rapid rate. One day it occurred to me that the old Kyiv was disappearing from the face of the earth. Now we can see clearly that the old city has practically vanished. But in those years this process was only beginning, but it was very vigorous. I saw that a city that had almost never been depicted in drawings was disappearing.”

But there are photographs.

“In spite of being very accurate, a photograph is lifeless. It is a life that, just like in fairy tales, someone’s evil has stopped and turned into stone. But a picture is alive in a mysterious way. That’s why it is the most convincing presentation of eternity.”

There was a time when the Union of Artists branded you as a “slanderer of Soviet reality” for the “Gateways of Old Kyiv” series of illustrations.

“When an individual clings to an idea, all the rest recedes into the background. I was absorbed by Kyiv! In my opinion, there was almost no prominent architecture in it. But I truly feasted my eyes on the small yards and houses that had sprung up in Kyiv’s warm soil, as if they were shrubs and trees. Looking at these houses, you could learn so much about the tastes and needs of their inhabitants. One of the telltale factors is the number of stories and windows, the presence or absence of porches and balconies, the shape of the front door, and the style of roof. What else? For example, on a floor tile at the entrance to the Morozov house the words ‘Please do not spit on the floor’ are written in the old pre- revolutionary spelling. The people who lived in this house had a bad habit of spitting whenever they pleased. On a house on Velyka Pidvalna Street you can see the Roman greeting ‘Salve’ — ‘Hello’.

“If these and other old buildings were conceived, built, stood, and died, i.e., they passed through natural cycles, I viewed the new construction — pardon my convoluted wording — as the materialization of the idea of equality in standard ferroconcrete cells vested with a beastly capacity for endless procreation. My soul revolted against this inhuman process, and I began to commute to Kyiv every day and make sketches.”

The “slanderer” labor was probably a major nuisance for you.

“Yes, it was. But I am glad that I have never asked the Union of Artists for anything, nor did I expect any favors from it. There was only one thing that made me dependent on it: I needed its permission to hold a solo exhibit. Ironically, my first exhibit was held at, of all places, the Union building. But I always had good relations with true artists. I only fell out with the bosses. The Union of Artists was an organization that cared about the material well- being of its members. For example, when they would organize an exhibit, they would form a purchasing commission consisting of the same influential artists. So they seemed to be buying their own pictures with the Union’s money. There was also a ‘feeding trough’ called the Art Fund. For a handsome sum it would request a picture, say, Harvest Festival at a Collective Farm. It was very easy to turn out a picture like this, and you could earn a pretty penny.”

Did you really have no temptation to scoop a handful from that trough?

“Thanks to my wife, who is a God-send, I have never done hackwork in my life. For a while I had no income, and only she could have endured this patiently. We lived off her engineer’s salary for years. Only in the late 1970s did it occur to me that I could do copying, which usually brought in good money. It was a very natural thing to do for master artists in the old days. Museums throughout the world are full of copies. I began to do copying and there were a lot of orders. The fee was not very big but I was industrious, and this work brought me a decent income.

“These copies helped me win a prize at the annual international exhibit in Los Angeles, called the Malibu Art Show, although I have never been there. A woman who had placed some orders went to the US with the pictures and submitted them to the competition — I didn’t even know about it. At the time, a foreign artist could only exhibit five works. When my pictures were accepted, she was happy. Can you imagine her joy when she saw a small red flag on my stand, which meant that Valery Akopov had won? That’s when she confessed what she had done.”

“WHAT IS LEFT OF OLD KYIV TODAY?”

Mr. Akopov, in your book Sentimental Strolls through Old Kyiv, you write: ‘When I am in the city, I walk sadly past old houses. This is not the previous sadness that accompanied me during the fifteen years that I was painting old Kyiv. That sadness assailed me from time to time; it was a deep, agonizing feeling over the unenviable fate of beings that were dear to me. The sadness I feel today is calm, cool, motionless, and, what is more, fruitless — like permafrost. It is a simple and clear-cut understanding of the fact that an entire cultural era has gone for good.’ These are sad words. Have you stopped loving Kyiv?

“What is left of old Kyiv today and what I still love are the city’s green spaces, like the hills above the Dnipro River and the outskirts. And what has Kyiv been turned into? Before, when I used to stroll down the streets with my friends, I could talk with them. Now, even if I shout, I cannot hear myself. It is impossible to live in Kyiv now. And I am happy that we have an apartment in Brovary, where I can see the sky from our balcony.”

What happened to the “Old Kyiv” series? At one point the Tretiakov Gallery wanted to acquire it.

“It wanted to. But I created it for Kyiv, and it should belong only to this city.”

We would like to hope that it will belong to Kyiv. Admirers of Akopov’s work are collecting his pictures so that in time they will be donated to the Kyiv Landscape Museum. The idea of establishing this museum is being discussed in various circles. Liudmyla Mykhalevych also broaches this subject in her documentary film. She first saw Akopov’s landscapes in his Podil studio, when he was just beginning to work on this series.

“Although they are simple in execution and concept, they nevertheless left an imprint on my mind,” Mykhalevych recalls. “At first I couldn’t understand: an old little wooden house, a bent street pole, a patch of grass sprouting from a sun- baked road, or a slope with first snow, which is tentatively covering up the vestiges of a summer that has ended, churches, narrow streets, and backyards with their permanent residents — cats and dogs. What is in them? They preserve the special atmosphere about which Akopov said later in his book Sentimental Strolls through Old Kyiv that it engenders a faint flickering light in the soul, which you want to catch and paint its warm reflection. Mr. Akopov has done everything to protect this faint light. He did this for us. But, what about us? Will we really let this light go out?”

THE DAY’S REFERENCE

Valery Akopov was born in Kyiv in 1939. He is a landscape painter of the realist manner, a follower of the finest traditions of old masters, and a member of the Union of Ukrainian Artists. From 1972 to 1986, using India ink and pen exclusively, he drew landscapes of the old, quickly-vanishing Kyiv to which very little attention was being paid at the time. He has had many solo exhibits both in Ukraine and abroad. In 1993 he was the winner of the Los Angeles-based annual international exhibit, Malibu Art Show. Akopov is also a poet, prose writer, and essayist, whose works have been published in Kyiv and Moscow.

Випуск газети №:

№36, (2007)Рубрика

History and I