Why hasn’t January 22 become a red-letter Day?

Friday, an exposition of competitive project proposals for a monument to the Unity of Ukraine in Kyiv opened at the National Artists’ Union. Despite the lamentable choice of designs and the absence of new ideas, including the image-bearing core (a fact stressed by experts as well as visitors), one wanted to go there to see whether January 22 had become a fact of public life in Ukraine. People on the street, when asked about the special occasion — the second one held at the highest level, with the attendant pomp, meetings, conferences, exhibits - either shrugged or gave vague answers (even this author’s friends, well acquainted with our history, were not too sure).

It should be noted that we have two important dates in January 2003: the 85th anniversary of the Fourth Universal [Decree] of the Ukrainian National Republic (historians still argue about the date, insisting that the UNR appeared on the world arena January 25, not 22) and 84 years ago, the Act of Unity of the Ukrainian Lands was proclaimed on St. Sophia Sq. in Kyiv, whereby the Western Ukrainian People’s Republic joined the UNR as a self-governing body. The Act reads in part: “From now on the Ukrainian nation, liberated by its own mighty forces, shall have an opportunity to combine the efforts of its sons to create an indivisible Ukrainian polity for the good and happiness of the Ukrainian people” (“Constitutional Acts of Ukraine: 1917-20”).

A closer look at the events of that time allows us to sum up the 4th Universal and the Act with the words, at long last. Regrettably, the considerable inner potential of the Ukrainian revolution, alongside its Russian counterpart, gradually scattered. The third Universal, issued by the Central Rada in the aftermath of the Bolshevik coup in Petrograd (Nov. 20, 1917, New Style), failed to take stock of the situation. It continued in the vein of a federal alliance with Russia, which made no sense under the circumstances. Ivan Nahayevsky wrote that “Hrushevsky’s call for raising from the dead the state organism of Moscow, which ever since the Council of Pereyaslav had been ruining the Ukrainian people, their rights and freedoms, not only failed to exert any influence on the Ukrainian citizenry, but also discredited Hrushevsky as a statesman in the eyes of the Ukrainian people.” All political trends in Russia, ranging from the monarchists to the Bolsheviks, fought for a single and indivisible Mother Russia. In the meantime, the Ukrainian Central Rada, dominated by Socialists, was disarming the Ukrainianized front-line units (meaning hundreds of thousands of combatants), believing that the “people’s militia” was the army’s counterweight. It was thought that the army “has been and will remain a weapon of the ruling classes in their struggle against the peasants and workers.” When it came to defending the national revolution (January 30, 1918), at the railroad station of Kruty, 3,000 Bolshevik men under the command of Colonel Muravyov overpowered 420 (sic) Central Rada defenders, of whom 300 were Kyiv college students. There were two to three thousand combatants left in Kyiv, the rest had left to divide plots in their villages.

Apparently, a desire to unite the un-unitable — being Socialists and patriots at the same time — and to postpone solutions to the most pressing social problems (above all, those of the land and peace) the UNR collapsed shortly after. Their demise was also due to utterly ignoring realities, with forces actively operating in Ukraine that were manifestly opposed to national independence (Bolsheviks, democrats, Russian monarchist, the Third Rzeczpospolita, the German and Austro-Hungarian empires, the Triple Entente countries, Romania...). January 26, Red Army forces broke through the Kyiv defenses and staged a mass terror. Almost 5,000 persons were butchered on Kyiv streets and shot by Cheka squads in the early days of the “triumphant march of Soviet power” in Ukraine.

Even though the Act of Unity was not implemented at the time (and nor could it have been under the circumstances), it would remain for decades on end an historic landmark for the nation. It never came to real unity. Whereas the government of the republic beyond the Dnieper took the Socialist stand, that of Halychyna fought the newly established Polish government for Lviv and professed the liberal-democratic principles of national state construction. Serhiy Lytvyn wrote, “Different ideological and foreign political orientations made the idea of unity fictitious and further divided Ukraine into East and West.” Simon Petliura wrote, “Actually, the idea of a United Ukraine was just a phrase.” The defeat of the national revolution was a matter of time. The tragedy of Ukraine was that its leaders lacked the technology of state construction and did not unite together around liberal democratic principles and a reasonable social policy.

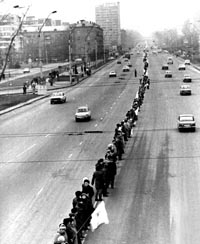

Regrettably, the split between the East and West, between the many regions in Ukraine — something all those hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians forming the live chain January 22, 1990, were so eager to bridge — is still there.

The Day has stressed on more than one occasion that this country, gripped by a heavy systemic crisis, must impose a moratorium on further pompous monuments. It takes hard work to overcome passivity and degradation, so all such monuments must wait. In absence of unifying public and national efforts, such unjustifiably expensive showcase projects will only irritate the people, which is quite understandable. We have enough symbols and more than enough to spare that symbolize nothing except bad or, at best, dubious taste