Ancestors of forgotten “Shadows”

…became the heroes of an exhibition dedicated to the legendary film by Serhii Parajanov Mystetsky Arsenal, Kyiv)

Can you tell where the “Shadows” are in the film, which is over 50 years old? And where actually are there the forgotten ancestors? Why did Kotsiubynsky call his story like this anyway?

Ivan Mykolaichuk, leading star of the film, once explained it to me like this: the writer, as well as the director after him, told a story about pagan beliefs – the ones that survived in the days of Christianity. In the 1960s, when the movie was shot, Christianity did not look like a modern form of beliefs. What to speak about Paganism? It has long gone with the water, as did the wooden idol of Perun, which had been dropped into the Dnipro and had a group of terrified Kyivans running after it and shouting “Vydybai, bozhe!” (God, emerge! – and it did emerge, right at the place where Vydubychi monastery was built later)...

“VYDYBAI, BOZHE!”

... Gone with the water, indeed. But it was preserved in the Carpathians, as Mykolaichuk explained. And the film crew of Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors had found this pagan polytheism – the worship not of the creator, but of the creation, the belief in universal interconnectedness, the richness of spiritual meaning and symbolism. Although even a hundred years ago, when Kotsiubynsky wrote his story, he noted that this phenomenon had diminished. “Now there are fewer devils,” went a popular saying he wrote down, “because they work in factories, near the machines, on the phone, on tracks, and bicycles.” That is, they had already been harnessed to work on machines. And they were meant to be kept away not only from cows or horses, but from any living being. And the last year I overheard a priest in Kryvorivnia say: “There are no more Molfars, evil wizards, in Carpathians.” The area has been purged...

Perhaps those Molfars went to Kyiv. For what is the meaning of such an exhibition, which returns us to the sources of Shadows..., to the ethno-cultural space that begat this phenomenon? The exhibition organizes Kyivans, so that they could repeat the legendary race along the Dnipro with cries “Vydybay, bozhe!” A critic from Moscow Mikhail Bleyman once wrote an article about archaists or innovators. At the first glance it looks like something new, so it must be so innovative. But the film’s structure was built on hopelessly outdated, obsolete things: ritual dances, shamanic sounds, divination rituals and charms to make life more amenable to man. Why do that, when there no longer were shamans in the Soviet Union, even the Christian church was shown the way? Everything was replaced by the communist state and its mythology, and its commitment to human was (at the time) an axiom. It was not a long-lasting thing either, as it turned out.

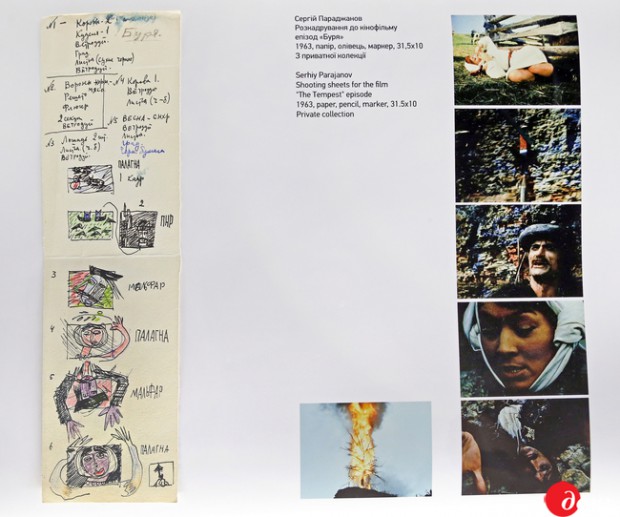

In this regard the exhibition at the Mystetsky Arsenal, which gathered a large and grateful audience at the opening ceremony, returns Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (not only the movie, but the story by Kotsiubynsky and the plethora of accompanying texts) to their true context. Is this archaic? Well, times change, and now the thing archaic is the shamanism of Bolsheviks, built on the myth of a communist heaven on earth after the abolition of private property and ownership instincts. And here is paganism, which is often called today “the ethnic religion” with its complex mythology and a fairly complete picture of the world. This picture is being brought into the spotlight by the exhibition, organized by the Art Center of Pavlo Hudimov “Ya Gallery,” Mystetsky Arsenal, FILM.UA Group, and other organizations, including National Film Center and Film Studio both named after Oleksandr Dovzhenko.

WHO’S NEXT TO GO WITH THE WATER?

However, the journey through all nine exhibition halls begins with quotations from Parajanov’s letter to one of the Communist Party Central Committee secretaries. He wondered: near his home a department store called “Ukraine” was built. This title, he argued, would have suited better to a museum, in which people would go not for another pair of pants, but for acquaintance with the achievements of the national culture... Well, dreams come true. Parajanov’s wife, Svitlana Shcherbatiuk was among the first whom I saw at the exhibition. She was very pleased with everyone she met, and happily told me: “Here it is the foundation of the Parajanov’s museum, of which we have been speaking for so many years.” Indeed so! Although the organizers plan to show the exhibition in other cities of Ukraine, and then France, US, Canada.

Photo by Mykhailo PALINCHAK

Five minutes later, I met excited Zaven Sargsyan, the legendary director of Parajanov’s Museum in Yerevan (the museum functions since 1989). He was very happy with what he saw: great! And right at the spot he attentively listened to Liudmyla Lemesheva, art critic from Kyiv, who told some interesting and little known, even to Zaven, stories of Parajanov’s life. One can’t help but think that the artist’s life and work are an infinite discovery, and will never be known fully. A mythological person, what more can I say?

The exhibition is “crucified” over a number of key concepts and symbols. Already at the entrance we read the word “reincarnation.” Anton Lohov presents the text and the installation of a Hutsul house – disassembled and assembled again in new, so to speak, socio-cultural format. The meaning, as I understand it, is this: Parajanov did the same thing; he deconstructed the Hutsul picture of the world and put it together himself. It turned out similar and different at the same time. Art film, again, is built on the foundation of the mass collective culture.

There is a famous example from Shadows... – the marriage of Ivan and Palahna, when they are being put in a yoke. It’s fictious, as no such tradition existed in the wedding ceremony; it’s the author’s addition by Parajanov. Several contemporary directors were invited to film their own version of the episode. The works by two of them, Ihor Podolchak and Kirill Serebrennikov, were presented. Andrii Alfiorov, one of the exhibition’s curators, assured me that several more directors have promised to do such a work later.

At the finish of the exhibition journey you will find yourself in the woods; the woods are another mythological character in its own right in the movie, and along with that – in the exhibition. The woods are personalized just the same – every tree has its soul and its revelation. This reflects the peculiarity of space, as mythology is being created by personalities. Each of the film’s co-creators has their own iconostasis and their own legend, visually embodied here, at the Arsenal. You can find, for example, a Transcarpathian artist Fedir Manuilo. As we know, it was after visiting Manuilo’s exhibition in Kyiv, that Parajanov had the idea to make a film on this material...

Maybe after visiting this exhibition, some young artist (and young people prevailed among the Arsenal’s guests) will have in their soul an idea to create their own world. But they should not abandon the world that was built before them. They should not drop the gods into rivers, and neither into the historical abyss – too big a risk to break the organic harmony of life. And what a work it would be later to bring it back!

Hats off to all those who had invented and built this exhibition. The feeling is that something new is being born in those halls. However, just at the exit I heard some alarming information: Natalia Zabolotna, head of the extremely successful Mystetsky Arsenal, is being moved aside by the masters of our lives. Too large an area, too much money is at stake here. The mountebanks understand nothing here – they have their own reasons and plans. Hopefully, we will prevail against them together. Let them go with the water – as always, on top. Just let them float past us, in the deafening silence of the people. And let them not emerge anymore. These shadows should go into oblivion.