First and second hetmanates in Ukraine

Cossacks and state-builders: a breakthrough into the future

It became clear in the mid-17th century that the old Ukrainian aristocracy, whose roots went back to the era of ancient Kyivan Rus’-Ukraine, was now unable to show authority among other societal strata and play the role of a generally-recognized leader. The uprising of Prince Mykhailo Hlynsky was the last attempt to demonstrate its political clout in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. After the uprising’s defeat, throughout the 16th and in the early to mid-17th centuries, the Ukrainian nobility proved incapable of taking resolute political steps and contented itself with a secondary role in Lithuania and the Crown, resorting exclusively to legal oppositional activity in the field of national culture.

Therefore, the aristocracy had to hand over the cause of national self-assertion and continuation of the statist tradition to other social strata, as was the case in many countries of Europe. Cossackdom turned out to be this new stratum. It is the Cossacks who were destined to pick up the baton from the previous Ruthenian “classocracy” which had long been in a state of degradation and destruction. Cossacks proved to be able to steer spontaneous protests of various estates into the channel of a longtime national liberation struggle against Polish domination. This powerful movement eventually resulted in the liquidation of Polish administration in Ukraine and establishment of the First Hetmanate, an independent Ukrainian Cossack state.

Cossackdom emerged as an estate that combined the features of what seems to be antagonistic strata – peasantry and boyars-warriors, or the nobility. Viacheslav Lypynsky, the theoretician of Ukrainian conservatism, regarded this syncretism of Cossacks, their readiness to induct into their ranks the active elements of other strata, as a valuable state-forming feature that earned the Cossacks high prestige among the other social groups at a time when the old aristocratic elite was steadily losing it.

The scholar notes that in the 17th century, the era of Bohdan Khmelnytsky, Cossackdom “rallied under this new name the healthy remnants of the old Ukrainian nobility and the best part of the bold and militant peasants who were ready to sacrifice themselves for the entire nation.”

From the very outset, when Cossackdom was forming, to a considerable extent, out of the peasantry, there were a lot of nobles in its milieu, who wielded a great deal of clout and instilled elements of their world-view, daily routine, and customs in the new stratum. The ranks of Cossacks were considerably topped up with remnants of the recently strong body of warrior boyars – the lower social category of Ukraine’s feudal chivalric stratum – in the mid-to-late-16th century.

Following the Union of Lublin and recognition of noble rights only for those who could documentally prove land ownership and nobility, a large number of petty land and mailed boyars, as well as branch nobles and armed servants, were to be reduced to the lower social rank. After 1569, a considerable number of Ukrainian petty knights in the southern Kyiv and Bratslav regions, who followed their traditional way of life connected with defending the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state’s borders, were deprived of support and societal recognition. A part of this estate joined the Cossackdom, thus bringing the “chivalric spirit” into its milieu and essentially forming its class face as well as political and social requirements.

As a result, the Cossacks, who took part in military campaigns and battles together with the nobles, were more and more convinced of being equal to the latter. There is a lot of evidence that Cossacks considered themselves knights. Cossack letters and documents abound in such titles as “Zaporozhian knighthood” and “knighthood of the Zaporozhian Host.”

The term “knighthood of the Zaporozhian Host” is used by both King Sigismund III and many other military figures and statesmen. Erich Lassota, the envoy of Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, who visited Zaporozhian Sich in 1594, calls Zaporozhians “knightly society.” Somewhat later, Cassian Sakowicz, Rector of the Kyiv Brotherhood School, called Petro Sahaidachny “noble knight” in the tribute poem.

Admitting representatives of the military-noble estate to their milieu, Cossacks made use of their military experience, borrowed their world-view, and gradually found common interests. Adapting and reconsidering their views, they were becoming part of the Ukrainian Cossackdom and forming the identity of it as a self-sufficient stratum.

The transformation of Cossacks’ socio-conceptual attitudes was accompanied by the evolution of their economic activities. The newly-emerged registered Cossacks were trying hard to secure their property rights, be exempt from taxes, get rid of the arbitrary rule of local starostas, diversify their economic activities, and liberalize the right to land ownership, free trade, cottage industries, vodka distillation, fishing, etc.

On their part, unregistered Cossacks actively formed their own communities, seeking self-government and an independent economic activity. This category was called town Cossacks. Thus, in south-eastern Ukraine, next to the Zaporozhian Sich, the population was more and more “Cossackized” – they no longer recognized the Polish authority, staying in close contact with lower Cossacks.

Registered Cossacks were a privileged stratum of the population in addition to the nobility. Of course, it could not embrace all of the Cossackdom. Yet, in terms of the way of life, town Cossacks differed very little from registered ones, forming the “grain-growing Cossackdom” which was more and more integrating into the socioeconomic and cultural life of the entire Ukraine. Supported by the Zaporozhian Sich, in fact an independent body, town Cossacks were in turn forming “a state within a state” and trying to get rid of the Polish administration. They were gradually becoming engaged in the national and religious struggle the Ukrainian nobility, clergy, and petty bourgeoisie waged by legal methods.

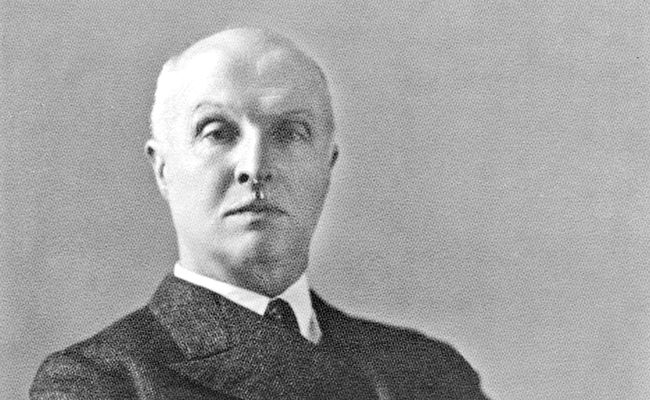

Photo from the website WIKIPEDIA. ORG

As the gentry became a synonym of British statehood, the Cossackdom became a similar national political notion in Ukraine. No wonder, many observers of Europe’s public life in the 17th century drew a parallel between the English Revolution of 1648 and Khmelnytsky’s rule. A lot of researchers note frequent comparisons of Cromwell and Khmelnytsky in the Europe of that time. Khmelnytsky established an essentially monarchic hetmanite power based on the “Cossack-noble, nightly-agrarian class.”

In the course of time, the Cossackdom comprised a growing number of settled well-to-do householders who colonized new lands, essentially expanding Cossack land tenure. Grave Cossacks gradually began to own considerable land property that could rival the settlements of an average nobleman. The key feature of Cossack land ownership was the use of hired labor, which shaped, to a considerable extent, the social behavior of Cossacks.

Arnold Toynbee pointed out an extremely important colonizational and civilizational functions of Cossackdom: “Just as modern Western empire-builders have overwhelmed their primitive opponents by bringing to bear against them the superior resources of industrialism, so the Cossacks overwhelmed the nomads by availing themselves of the superior resources of agriculture.” It is in the Cossacks’ economic activity that the English thinker saw “some signs that belong to the future rather than to the past.” This is why Cossack associations reminded Toynbee of the “colonial possessions of modern Western world.” This breakthrough into the future, from which the Cossackdom benefited, was caused by the formation of bourgeois relations within it, and this allows us to consider it a participant in important socioeconomic shifts that were occurring in Europe.

At the turn of the centuries, Cossackdom was formed as a separate estate which did not fit in with the Polish oligarch-magnate political system and began to be aware of its destination in the national liberation struggle of the Ukrainian people. Among the Cossacks were representatives of all the principal strata of society – from freedom-aspiring peasants to nobles who were dissatisfied with the existing system. This is why Cossacks expressed as fully as possible the Ukrainian people’s aspirations for freedom and an independent state, which made them an exponent of nationwide interests. No wonder, European contemporaries equated Cossacks with the whole Ukrainian nation, calling it “the nation of Cossacks.”

The social evolution of Cossacks turned them into an estate that proved to be the bearer of bourgeois relations and possessed features that exceeded the narrow limits of feudal corporatism. In this context, Cossacks share a lot of features with the British gentry. The gentry, new British nobility, formed at the same time period as the Cossackdom did – in the 16th-17th centuries. It became an important factor of the bourgeois development of English society. By contrast with caste-like isolation in the era of feudalism, both estates shared broad universalism – they combined military and economic activities and actively participated in the political and ethnic cultural life. The war with Spain and sea expeditions cleared the way for active and energetic elements among the gentry. Cossacks displayed similar enterprise – their maritime expeditions drew a wide response in Europe. While the nobility almost always considered it beneath knighthood to be engaged in economic activities, the gentry were willingly doing business, breeding flocks of sheep and setting up farms. Cossacks, especially well-off ones, were also mostly engaged in farming, and they did not know what serfdom was. Both the English bourgeois revolution and the rule of Khmelnytsky completed the evolution of ownership, turning both the gentry and Cossacks into bearers of a new – bourgeois – type of private property. Openness to other social categories was inherent in both estates. Every freeholder, who reached the property qualification of a 20-pounds-worth annual income, could join the gentry. As for the Cossackdom, free access to its milieu was a fundamental principle of its existence. After the formation of a Cossack state, transition from the Polish estate to Cossackdom only depended on a person’s ability to acquire gear for doing military service.

In English society, the word “gentleman” gradually lost its original social meaning and became a term that denotes the high moral and ethical status of an individual’s everyday behavior. The official documents of Elizabeth I’s era often include the term “gentlemen of reputation” – the nobility of these gentlemen was not connected with high birth or the office they held. The Cossack became the same kind of gentleman for the Ukrainian general public, for he rose above the nobleman or the magnate and became a model of social behavior, the bearer of all real or fictional virtues from the viewpoint of the pro-Polish majority. Both the gentry and Cossacks take over state-formation functions from the old feudal elite. In Ukraine, this became particularly obvious in the early 17th century, when Cossacks became the conductors of and active participants in the national liberation struggle of the Ukrainian people. In 16th-century England, representatives of the gentry entered the House of Commons and formed opposition to the feudal tradition. The gentry were assuming the offices of sheriffs, judges, municipals, etc. The leaders of the English revolution – John Hampden, John Pym, and Oliver Cromwell – came from the gentry. The Cossackdom nominated from its own ranks Sahaidachny and Khmelnytsky, who spearheaded state-formation and armed struggle of the Ukrainian people for their liberation. In the course of events, both estates underwent similar evolutions. The gentry’s upper crust became lords, but a considerable part of this stratum remained squires – small-scale landowners in the British provinces. The social differentiation of Cossacks prompted the Cossack starshyna (senior officers) to become big landowners who played for some time the role of the national elite and merged later with the Russian land aristocracy. On the other hand, the majority of Cossacks wanted to preserve the status of medium- and small-scale landowners.

Thus, by many indications, the Cossacks were emerging as a new class of “warriors-producers,” the development of which was in the same context with the underlying economic and socioeconomic processes then underway in Europe. It is Cossackdom that strongly influenced all the aspects of Ukrainian public life, particularly, ruination of the feudal system and formation of the capitalist setup, which was interrupted later by Russian czarism.

Photo from the website WIKIPEDIA. ORG

The gentry, new British nobility, formed at the same time period as the Cossackdom did – in the 16th-17th centuries. It became an important factor of the bourgeois development of English society. By contrast with caste-like isolation in the era of feudalism, both estates shared broad universalism – they combined military and economic activities and actively participated in the political and ethnic cultural life. The leaders of the English revolution – John Hampden, John Pym, and Oliver Cromwell – came from the gentry.

The socioeconomic evolution of Cossackdom considerably speeded up in the Khmelnytsky era. In the course of a liberation war, Cossacks, in the words of Viacheslav Lypynsky, “rallied all the elements that were against national slavery and defended the Orthodox faith, against the magnates’ economic exploitation and the nobility’s arbitrary rule. They revolted for the king against the kinglets.” Those were, above all, “the broad masses of gallant and militant peasants who managed to win, by shedding blood, the honored name of a knight and a Cossack. The broad circles of equally militant burghers merged with them. A mass of the Ukrainian nobility also joined the Cossacks from above, especially those who most stubbornly resisted the then Polish domination – old believers and fanatics of traditional Orthodoxy, enemies of the magnates’ oligarchy and the “golden freedom of nobles.”

Thus, Cossacks became the most influential stratum in Ukrainian society, and it was quite logical that they were trying to win over the interests of other estates, including the Ukrainian nobility – a traditional bearer of the idea of Ukrainian statehood.

As the gentry became a synonym of British statehood, the Cossackdom became a similar national political notion in Ukraine. No wonder, many observers of Europe’s public life in the 17th century drew a parallel between the English Revolution of 1648 and Khmelnytsky’s rule. A lot of researchers note frequent comparisons of Cromwell and Khmelnytsky in the Europe of that time.

Polish historian Ludwik Kubala, who considered Bohdan Khmelnytsky one of the most outstanding figures in European history, gave the Ukrainian hetman a comprehensive characteristic. “Foreigners compared him to Cromwell,” he wrote. “This comparison inevitably came to mind at a time when both of them attracted almost an exclusive attention in the west and east of Europe. The two flared up and faded away almost at the same time. Both were adversaries of the dominating church and system in their countries. Taking their hands off the plow in the late years of their life, they led uprisings and achieved successes that put to shame the knowledge of the most experienced generals and statesmen. Both formed powerful armies, which allowed them to gain an almost unlimited power and hand it down to their children before they died.”

At the same time, Kubala rates Khmelnytsky higher, for the space his authority was open and vulnerable from all sides, and, unlike Cromwell, he could not rely on well-trained intellectuals and the resources of an old and powerful state. The hetman had to create all kinds of things, such as the army, finances, a public economy, administration, relations with neighboring countries. All this was on his mind. “He had to choose and teach people, looking into the minutest detail,” Kubala points out. “And the fact that his army was not dying of hunger when he had weapons, cannons, gear, good spies and smart agents, and was never short of money, was his personal merit, quite enviable not only here in Poland. He was an uncommon man from all points of view. He stood head and shoulder above other talented people to an unlimited extent. We can say that he was born to be a ruler: he could conceal his intentions, did not hesitate in the decisive minutes, for he possessed an enormous willpower and a hand of iron.” Lypynsky gives this characteristic in his book Ukraine at the Turning Point which thoroughly analyzes state-formation in the last years of Khmelnytsky’s hetmanship. The last Hetman of Ukraine, Pavlo Skoropadsky, showed these traits of a political leader, who addresses not only large-scale state problems, but also less important at first glance but still essential matters, in 1918.

Lypynsky believes that Khmelnytsky’s hetmanship was the only period of Ukraine’s grandeur. This historical stage was associated with the victory of the Ukrainian “Cossack-noble classocracy” both over Poland and over “degrading tendencies within the then Ukrainian democracy that revolted against Poland.”

The hetman suppressed with “a hand of iron” the anarchic rebellions that erupted after each military defeat or irritating political action, such as the signing the Zborow and Bila Tserkva agreements, the Berestechko defeat, the Moldova campaign, the alliance with Turkey, Moscow, George Rakoczi, etc. At the same time, he was going to replace previous Polish lawlessness with laws on the status of peasants in the Cossack state.

Khmelnytsky established an essentially monarchic hetmanite power based on the “Cossack-noble, nightly-agrarian class.” This class comprised local, both Polish and Ukrainian, “knightly and material-producing elements.” Lypynsky points out that, by nipping in the bud “the Ukrainian democratic schedule and thanks to the classocratic conquest of Ukraine, Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky became the creator of a new Ukrainian nation, rather than a more radical democratizer of the Polish republican nation and state already contaminated with democratic rot.”

In Lypynsky’s view, “a strong authoritative and hereditary monarchy” was to play an important role in the making of an optimal “classocratic” society. He emphasizes that this monarchic power “is to be limited by the law, it is by no means autocratic, it is conservative but not reactionary, it guards the old laws but does not hamper passing new ones.”

Only this kind of “classocratic” monarchic power, limited by law, legally restricts “imperialism of the dominant aristocracy” and gives the latter the necessary moral authority in the eyes of the passive masses. This kind of power enables the new aristocracy to make a national (public and material) creative effort and ensures the formation of a new strong organic nation out of an active minority and a passive majority.

According to Lypynsky, the hetman’s “autocratic” power can limit itself if it secures the rights and self-determination of the new Cossack state’s main estates. Although Khmelnytsky ruled Ukraine “on his own” and was “an autocrat in a new meaning of the word,” he occasionally convened Cossack congresses in Chyhyryn, guaranteed estate courts and estate-based local administration. “These congresses, in which Cossacks, the clergy, and lower middle classes take part,” Lypynsky writes, “these sprouts of consultative representation of Ukrainian estates, as well as the estate-based local self-government, harbored a germ of the constitutional-monarchy system that made Britain, France, and Germany strong states and could have also made Ukraine a state like this, all the more so that our neighbors – a too free republican Poland and an unfree autocratic Moscow – were unable at the time to establish this system.”

Relying on the new aristocracy in his intentions to form a “supra-class Ukrainian hereditary monarchic power,” Khmelnytsky also took into account the essential socioeconomic shifts that had occurred in Ukraine and was trying to ward off the conflict of class and estate interests in the state. This aspiration was manifested, above all, in broadening the scale of Cossackdom and preventing the restoration of serfdom. The number of peasants turned Cossacks, who were granted Cossack rights, grew to hundreds of thousands. These circumstances resulted in the fact that, after the death of Khmelnytsky, corvee was not the main form of the exploitation of peasants for some time. The hetman in fact opposed an immediate separation of Cossacks from “Cossackized” peasants, postponing this for an indefinite time. This disengagement was never put in practice in Khmelnytsky’s lifetime.

In their turn, “Cossackized” peasants were aware that a strong hetmanite power was the institution that would secure their new social status, confirm the liquidation of serfdom, grant them the right to own land, and personal freedom.

With this in mind, contemporary researchers of the Khmelnytsky era are quite right to assert that Cossackized peasants and non-registered Cossacks were a social mainstay for establishing Ukrainian monarchism in the form of a Khmelnytsky-dynasty hereditary hetmanate.

Yurii Tereshchenko is a Doctor of Sciences (History) and a professor

(To be continued)

Newspaper output №:

№28, (2018)Section

Day After Day