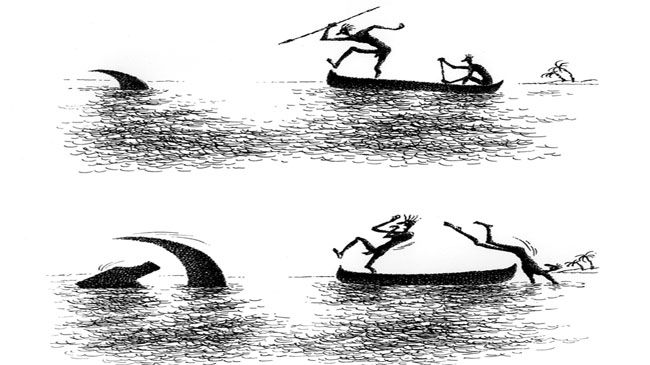

Playing with fire is unadvisable

The dangers of historical ignorance and undigested lessons of the past: marking the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution in the context of the Ukrainian Revolution

Revolution is never made to order; if there are no objective preconditions for its emergence, no one will be able to start the fire which would burn down the old society. However, when an old, completely worn out system of political and economic domination becomes an obstacle to the free (or simply normal) development of society, and a powerful revolutionary leader is there (speaking somewhat simplistically, when people are willing to make change happen and know “whom to follow”) – then, the revolution comes to the agenda in a harsh and inexorable manner. It is especially so when narcissistic upper classes are not able to make a realistic assessment of the nation’s situation, like in the Russian Empire during the reign of Nicholas II, exactly 100 years ago. They confidently looked forward to ruling many more years by the grace of God or something like that, until it suddenly ended...

Any historical analogies are flawed, and especially so when they are too loose. Getting to understand the laws of history would be too easy a task if it would be enough to find some basic outline or pattern in the past and apply it to the present. However, one can, and should, draw conclusions required by the current situation from an objective and unbiased analysis of the events which unfolded 100 years ago in Russia and in this country (the date is symbolic in any case, but symbolics may well serve as an ominous warning – it does happen that way sometimes!). Here is a very short presentation of these conclusions.

Firstly, the unreformed nature of the Russian society made itself felt (and the Russian Empire was just in that condition as of February 23, 1917, since the core of its political system, that is, autocracy, remained unchanged, despite all the economic advances made by 1914 and the democratically-theatrical scenery which included the Duma). It was a state plagued by brutal social oppression and imperialist domination. Idealizing such a state entity is inconsistent with the historical truth.

Secondly, it is clear that such a system had to fall, and it did ultimately fall. Why did it happen, in fact? Was it because Vladimir Lenin and his German sponsors (alternatively, Russia-haters in the Entente powers) maliciously sought to undermine stability in so-called “Holy Rus”? Or was the “Austrian agent” Mykhailo Hrushevsky to blame? This explanation is obviously not serious. The main causes of the Russian and Ukrainian revolutions (like with any truly great revolution) were internal. Without understanding this, we can hardly grasp anything.

Thirdly, the primary responsibility for the fact that the spontaneous revolutionary process of 1917 (and it was just that) so quickly got out of hand lies not only with the Bolsheviks, and not even mostly with them. Lenin was a uniquely talented “populist” (this term is eminently appropriate precisely in his case!), but had the Russian democratic politicians, who were able to speak so beautifully about freedom, really undertaken essential reforms instead, things would have turned out differently. It applies even more to the Ukrainian national democratic politicians.

Fourthly, with all due respect to the People with a capital “P,” one should always remember that the People, whether Ukrainian or Russian, easily falls prey to clever manipulation and turns into pliable “masses” (no wonder Lenin loved that word!). It is especially so in the modern media environment of the 2017 vintage. Experience of the Putinist regime (and the current master of the Kremlin is terribly afraid of the revolution and will resort to any violence to prevent it), as well as experience of a considerable subset of the Ukrainian media, show the catastrophic consequences of such turn of events.

So, let us learn in the brutal school of the past, and digest a harsh lesson: playing with fire is unadvisable! This was true 100 years ago just like it is now.

When announcing its intention to dedicate 2017 to discussing the revolutions in Ukraine and Russia, Den/The Day departed from the assumption that mistakes and miscalculations committed by our predecessors (internecine struggle, pernicious ambitions, egotism, political blindness, and inability to see hidden pitfalls) ought to be seen as warnings addressed directly to us. Let us emphasize once again: history does not literally repeat itself, but its conclusions (chief of them being that we need spiritual revolutions and radical reforms to avoid violent revolutions) are literally crying out to us today. Is it not a worthy topic for a year-long discussion?