Patterns of the universe

Patterns of the universe

Every country has a number of easily-recognized images that mark it on worldwide map of fine arts. Some countries are represented on this map by just a few universally known objects, while others have tens, hundreds, and even thousands of well-known visualizations. Among those rich in the pictures that call up an association in the mind is Italy, the birthplace of Etruscan and Ancient Roman art, the land where Eastern and Western art traditions intersected, and manifestations of the culture of severe European north could be combined with the objects of Byzantine or Arabic culture. It is here, after all, that the refined art of the Renaissance and the chimerical, subtle, and whimsical baroque lushly flourished, not to mention later periods of the rich Italian culture.

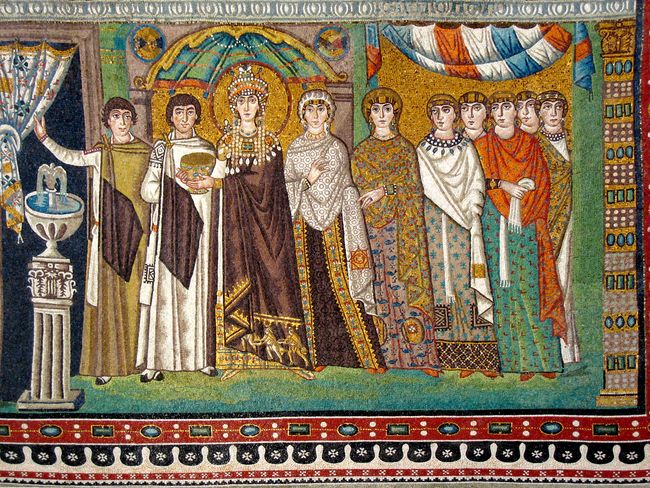

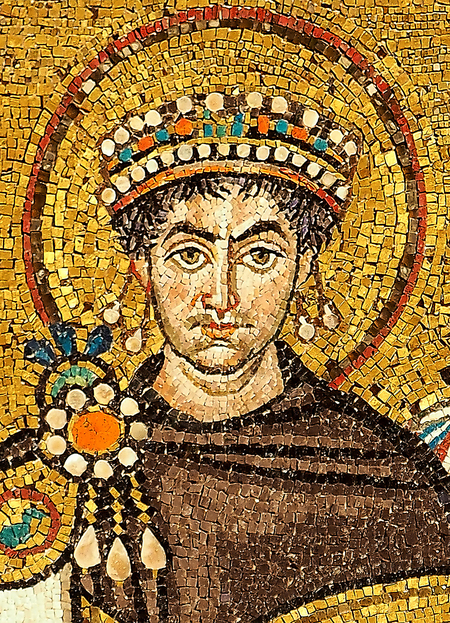

The universally-known images of Italy comprise the famous mosaics of Ravenna, which represent early Byzantine art. The Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, the Orthodox Baptistery and the Arian Baptistery, the basilicas of Sant’Apollinare in Classe and Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, San Vitale, and the Capella Arcivescovile comprise hundreds of world-famous images that are difficult to classify as more or less known. With due account of historic importance and, hence, frequent description in not only art-study, but also academic and popular books, the best-known ones are perhaps the portraits of Byzantine Emperor Justinian I the Great (527-565) and his wife, Empress Theodora (500-548), surrounded by male and female courtiers, respectively, on two mosaic pictures in the apse of San Vitale’s temple. The majestic supercilious glance of the stern Basileus and the refined sensuous look of the beautiful Basilissa remain etched forever on the memory of everyone who saw their portraits at least once.

No wonder the Ravenna mosaics have not only been drawing the gazes of the hundreds of thousands of tourists long since but have also become the object of thorough research by leading art historians all over the world. This also attracted the academics associated with Kharkiv University: Yegor Riedin (1863-1908) and Fyodor Schmit (1877-1937). Riedin, an apt pupil of Nikodim Kondakov, published the book Mosaics of Ravenna Churches in 1896 in Saint Petersburg in the Kharkiv period of his life (1893-1908), while Schmit, who chaired Kharkiv University’s Department of Art Theory and History in 1912-20, published several articles on the 12th-century Ravenna mosaics in the journal Svetilnik in 1914 and 1915.

Yulia Matvieieva, a teacher at the Kharkiv State Academy of Design and Arts, adequately upholds the traditions of Byzantine art studies in Kharkiv at present. The academic has been researching Byzantine church embroidery for about 20 years. In 2008 she successfully defended the Candidate of Art Studies dissertation “Evolution of the Byzantine Tradition in the Iconography of Late Medieval Liturgical Embroidery.” In the past few years, the historian of Byzantine art has been exploring the images of fabrics on Ravenna’s early Byzantine mosaics.

MOSAICS UNDER THE DOME OF THE ARIAN BAPTISTERY IN RAVENNA. THE CENTRAL PART SHOWS THE BAPTISM OF JESUS CHRIST, WITH THE FIGURES OF 12 APOSTLES AROUND

Matvieieva’s research, full of scientific discoveries and even sensations, was recently crowned with a fundamental monograph, Decorative Fabrics in Ravenna Mosaics: Semantics and Culture-Sense Context, which the researcher presented in early 2017 at Karazin University’s Dmytro Bahalii Center for Ukrainian Studies. This event was organized jointly with the History Faculty’s Department of the History of the Ancient and Medieval World and the Ukrainian-Italian Academic Center. Incidentally, before this, the academic had already delivered a lecture on this book at York University, one of Britain’s oldest ones, for which she prepared a special English-language edition of a part of this monograph – “Crossed Flowers and Circles: an Evolution of Eucharistic Symbols.” The unique design of both books, lavishly illustrated in color, was done by Oleksii Chekal, a well-known art historian and designer, a teacher at the British School of Design, and founder of the Kharkiv School of Calligraphy.

The 5th-7th-century Ravenna mosaics are incredibly full of the images of fabrics – from the clothes of human characters to a symbolic depiction of the sky which is also shown as a fabric in the shape of an umbrella that covers the earthly world. Each of these images conceals a profound symbol, and none of them is ill-considered or accidental. As Matvieieva proves convincingly, the mosaics attached special importance to depicting fabric, which underlines a very particular significance of textile items in the ecclesiastical and lay everyday life and rites and even in the world-view of people at the time. For example, what attracted the researcher’s attention was the image of Theodora and her retinue full of endless variegated fabrics. Each of the fabrics on this famous picture had its own symbolic meaning, and their appearance and placement in the mosaic can disclose the new facets of scientific knowledge not only about traditions of the Byzantine imperial court or church, but also about the personality of the empress herself. The Kharkiv researcher proves that, in all probability, Theodora personally commissioned the picture and could take part in the general planning of it. No less interesting is the researcher’s observations about the depiction of fabrics in the domes of early Byzantine baptisteries, where they helped reveal the essence of the sacrament of Baptism and the feast of Epiphany.

THIS MOSAIC DEPICTS THE PALACE OF THEODORIC THE GREAT, KING OF THE OSTROGOTHS, IN RAVENNA. THE PICTURE IS AT THE BASILICA OF SAINT APOLLINARIS BUILT IN THE LATE 5th – THE EARLY 6th CENTURIES

What also draws special attention is the image of cruciform flowers in many mosaics, which researchers used to regard as a purely decorative element. As the art historian has proved convincingly, the depicted flowers are mallows which had been used as food since ancient times and thus called up a strong association with bread. Interestingly, in the languages of many Mediterranean peoples, this flower’s name is directly linked to the name of bread. Moreover, even in the Ukrainian language, another name of the mallow – “kalachyk” – means a bread-like item, a small “kalach,” and one more term – “prosfornyk” (“prosvirnyk”) – compares the flower not with plain bread but with communion bread in church. Therefore, in the Christian context, a mallow meant bread as not earthly food but as the food of Resurrection, which Christ gives – it is the Eucharist, the Bread of Life. Taking this into account, the many images of this flower, which stylistically emphasize the cross-like shape and the bread allusions, can in no way be a purely decorative element – they symbolize the Holy Communion as guarantee of Salvation and Eternal Life.

A short newspaper article does not allow one at least to enumerate the outstanding discoveries and profound observations Matvieieva made on the book’s pages. Even during the presentation, which lasted for almost an hour and a half, the author could only describe a small part of her work in general outlines. Yet the whole audience remembered the central idea very well: the mosaic pictures with all the inherent images on the walls of Ravenna’s structures of worship serve as a canvas, a curtain, which separates the earthly world from the other, heavenly, divine one. So the mosaic pictures seem to be woven on valuable golden textiles that form a wonderful majestic tabernacle adorned with fine ribbons that bear golden embroidery, pearls, and precious stones. It is a tabernacle of the heavenly church in the divine world. The image of a tabernacle produced an effect, when, under a twinkling illumination of the temple’s inner space, the mosaics seemed to be moving, playing with various colors, and fluttering like a piece of fabric in the wind – and the images were coming to life, becoming three-dimensional, and finally materializing. They were going from a symbolic world into a real one. The Byzantines viewed God the Creator himself as a divine builder who created the sky in the shape of a tabernacle: “Who coverest thyself with light as with a garment: who stretchest out the heavens like a curtain” (Psalm 104:2).

Newspaper output №:

№21, (2017)Section

Society