A restorer of the Ukrainian nation

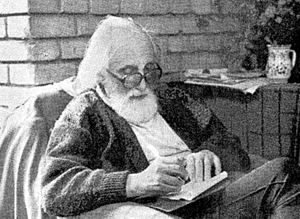

Mykhailo Braichevsky, historian, thinker, and statesman

One cannot be just a historian in a totalitarian state with its intolerance of any manifestations of disobedience in the cultural sphere. There are the ever vigilant “priests” of the only correct ideology who consider any attempt to seek the Eternal Truth (which does not depend on tsars, general secretaries, pharaohs, sordid priests, venal journalists or researchers) as an act of treason. They force you to constantly praise the incomparable virtues of the Big Brother. Should a historian wish to serve his people, rather than some phantom ideology (like the “Soviet people” as a “new historical community of man”), his act of treason would be far graver and punishment much harsher. This is especially true when such a historian regards loyalty, dedication to his people as the main criteria in describing the characters of his writings. Ukraine appears to be the only country where praise is lavished on national historical figures who faithfully served another country (Muscovy, the Romanovs’ empire, the USSR), rather than Ukraine, and where those who fought for the independence of their native land are anathematized. What can be more frightening and absurd? Ours is a nation whose eyes were put out and spine broken.

This was something the best Ukrainian historians of the 20th century knew only too well.

Mykhailo Braichevsky (1924-2001) was one of them. Rereading his works, meeting with people who knew him, reading his friends’ memoirs, one realizes the great scholarly legacy left by this personality, which goes far beyond pure science. He is the author of such internationally acclaimed works as The Origin of Rus’ (1968), When and How Kyiv Came to be (1963), At the Roots of Slavic Statehood (1964), Annexation or Reunification? (1966), The Assertion of Christianity in Rus’ (1988), and the recent fundamental monographs Sociopolitical Movements in Kyivan Rus’, Historical Thought in Kyivan Rus, Rus’ and Khazaria, Askold – Tsar of Kyiv. He was a prominent historian, a keen thinker, and a gifted statesman. His prophetic ideas remain topical. In a way, Braichevsky was a brilliant archaeologist charged with one of the most important missions in the field: restoration. He was a restorer of the Ukrainian people’s past (cleansed of dogmas, myths, tags, and abusive second-ratedness) and, consequently, a designer of its future. He was the incarnation of decency, integrity, and fairness in the historical domain. He was a model citizen and patriot of Ukraine because he didn’t want to carve out a career by making concessions in principal matters (in fact, he wouldn’t know how to go about it).

Who knows, maybe it ran in his blood. Mykhailo Braichevsky came from an old Ukrainian aristocratic family (once Polonized but in the 20th century they became aware of their national identity; not coincidentally, his father Yulian sent Mykhailo to Ukrainian School No.83 on Liuteranska St. in Kyiv, although it was reorganized as a Russian school on the tide of the struggle against “nationalism,” something Mykhailo would remember for life). Or maybe it was his inability to bow and scrape before any scholarly or government authorities, an attribute seldom found these days, something instilled by life.

In 1948, after graduating with honors from the Faculty of History of the Taras Shevchenko University in Kyiv (particularly, after founding a student scholarly society and presenting his report “The Origin of the Ukrainian People” at one of the sittings, a topic he would study for almost the rest of his life), he became a research fellow with the Institute of Archaeology at the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR. There he studied Slavic antiquities and interrelationships between old Slavic lands and provinces of the Roman Empire. Before long this scholarly quest led him to what was best described as political and ideological minefields. In the mid-1950s, Braichevsky came up with the idea of identity of the Cherniakhiv culture (originated around 2nd century AC, Eastern European forest steppe) and an Eastern Slavic intertribal association mentioned in Byzantine chronicles as the Antes, and in Old Rus’ ones as the Polans. A markedly seditious concept at the time (and nowadays, as well) because the young gifted archaeologist, Mykhailo Braichevsky, was actually supporting Mykhailo Hrushevsky’s “bourgeois nationalist” theory whereby the Antes started the process of building an Eastern Slavic state and had a decisive influence on the maturation of Old Rus’ with Kyiv as its capital (and this considering that Hrushevsky unequivocally pointed to the Antes as the direct ancestors of the Ukrainians).

In 1955, Braichevsky finished his candidate of science thesis “Roman Coins on the Territory of Ukraine.” Five years later, as the author of large chapters in the joint monographs Sketches on the Ancient History of the Ukrainian SSR and The History of Kyiv, he submitted a doctorate work but met with strong resistance even in the course of preliminary discussion at the Academy’s Institute of Archaeology. In the end the doctorate was rejected, on ideological rather than academic grounds. That same year 1960, Braichevsky transferred to the Academy’s Institute of History. There, together with Olena Apanovych, Olena Kompan, and Yaroslav Dzyra, he became one of the biggest stars in the historical and cultural division of the Sixtiers movement. It was in 1963-68 when he wrote the fundamental monographs When and How Kyiv Came to be, At the Roots of Slavic Statehood, The Origin of Rus’, and his famous article Annexation or Reunification? Before long these works were published in Western Europe and the US, making Braichevsky known far beyond the borders of Ukraine.

Each of his works was a grain planted in a fertile soil that grew in the field of Ukrainian national consciousness, even though the latter was only awakening after long decades of lethargic sleep under Stalin. There were several such grains. Let us consider each briefly.

HOW AND WHEN KYIV CAME TO BE. After comparing and thoroughly analyzing documented evidence contained in Byzantine and Old Rus’ chronicles, even Scandinavian and Armenian legends, Braichevsky arrived at the conclusion that the semilegendary Kyi was a perfectly real historical figure at the head of a powerful Slavic state formation, a Polan prince; and that the famous Askold, the ruler of Kyivan Rus’ in the 860s-880s, was at the head of the Polan Kyiv dynasty, never a Varangian! It was Askold who made the chronicler-glorified campaigns against Byzantium, not Prince Oleh (his murderer), eulogized by Pushkin.

THE ORIGIN OF RUS’. This well-known monograph contains, perhaps, the most fundamentally substantiated refutation of the Soviet propaganda theory of the common origin of the Russian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian peoples, their common (not even close!) history and culture, which concept was meant to prove the historical “inevitability” of their merger – i.e., disappearance – especially in the case of the Ukrainian people. Braichevsky attacked this concept in a serious scholarly manner, using well-documented evidence. He demonstrated that linguistic, archaeological, anthropologic, and written sources contain irrefutable proof that an association of Slavic tribes known as Rus’ in the 9th century emerged in the Eastern European (i.e., Ukrainian) forest steppe, with the nucleus in Naddniprianshchyna (Dnieper/Dnipro Ukraine), including Kyiv, Chernihiv, and Pereiaslav. The territories to the north and northeast were then inhabited by other ethnic groups. Slavs settled there much later. In view of this, Braichevsky insisted, the indigene inhabitants of those territories were the ancestors of each of the Eastern Slavic peoples that would settle there later. The scholarly and political importance of this statement is hard to overestimate.

AT THE ROOTS OF SLAVIC STATEHOOD. A monograph submitted by Braichevsky as a doctorate work and turned down by authorities. In this book he developed and upgraded his views as a historian on the Cherniakhiv culture in the forest steppe, compared to the Polan settlements as a people that would build an Eastern Slavic state. The roots of Eastern Slavic statehood were to be found not among the Normans, not in Novgorod, Ladoga, Khazaria, not in the forests of Suzdal, but in the middle of Dnipro Ukraine. This simple inference met with severe resistance from the imperial dogmatists.

ANNEXATION OR REUNIFICATION? This famous article appeared after the administration of the Academy’s Institute of History assigned Braichevsky the task of writing about the Treaty of Pereiaslav and its outcome for the Ukrainsky Istorychny Zhurnal (The Ukrainian Historical Journal) in 1966. This was an ever-important topic for Ukraine and the big question was what happened at the time: annexation or reunification? The notorious “Theses of the CC of the CPSU on the 300th Anniversary of the Pereiaslav Act” read that it was a reunification of two brotherly peoples. That reunification actually meant absorption of Khmelnytsky’s Ukraine by Muscovy, with all the grim consequences. The institute administration, being aware of Braichevsky’s “nationalistic” moods, must have wanted to direct his work along the lines of official Russian historiography, but the result turned out to be the exact opposite.

In the article, Braichevsky profusely quoted from Marx, Engels, and Lenin (standing procedure at the time), convincing the reader – doing it with confidence, relying on irrefutable evidence – that the so-called reunification was actually a brutal aggressive act against Ukraine; that it threw Ukraine back to the most primitive form of feudalism, causing regress in its political, cultural, and economic life, which would be very difficult to overcome; that it dealt a devastating blow to the national state-building process.

Remarkably, he did not use samizdat for his glaringly dissident article but submitted it to the official journal of the Soviet Ukrainian Academy’s Institute of History, and kept the second carbon copy at his office, making no secret of the fact and lending it to whoever wanted to read it. “Upstairs,” however, were anything but touched by the prominent historian’s naivety. He was called on the carpet for reminding of his seditious monographs, his resolute refusal to repent, insisting on the scholarly maturity of his works (admitting only that his works had been translated and published in the West without the author’s know-ledge and consent), his active participation in the Creative Youth Club, in 1962-65 (with Stus, Horska, Symonenko, Chornovil, Drach, Pavlychko, Taniuk, to mention a few noted dissidents), when he read brilliant lectures on the history of Kyivan Rus’ and ancient Kyiv. This, of course, could not have been forgiven.

In 1968, Braichevsky, Yaroslav Dzyra, Olena Kompan, and Olena Alanovych were dismissed from the Academy’s Institute of History on grounds of staff reduction (sic! – Author). Months of forced unemployment that followed did not dampen his creative energy. It was during that period when he demonstrated civic courage and talent, saving the architectural ensemble of today’s Kyiv Mohyla Academy from replanning (the administration of the then naval college wanted to build a large sports complex with a swimming pool) and the ancient buildings in Podil from being torn down and replaced by a city microdistrict. Braichevsky was a very good painter, literary critic, and writer (e.g., the historical detective story The Murder of Princes Borys and Hlib).

In 1972, a new stronger wave of repressions hit the outstanding scholar. Braichevsky was dismissed from the Institute of Archaeology, in retaliation for “serious theoretical errors and methodological shortcomings.” It equaled to being expelled from science and blacklisted at the time. All copies of the books by this world-famous scholar were confiscated from the libraries. Books mentioning his name, even in a critical context, were banned. Everything pointed to imminent arrest. After Braichevsky fell seriously ill and sustained three consecutive complicated surgeries, a KGB man shared the same hospital room as a “patient.”

Braichevsky won in the end and returned to active life and scholarly work. He was officially recognized as Doctor of Science in 1989, when he was 65. Few will recall that he spoke during the Rukh constituent convention in September that same year, presenting one of the main co-reports entitled “The Roots, Progress and Prospects of the Ukrainian Statehood” (those interested enough can look up Literaturna Ukraina, [12 October 1989. – Ed.], to see that the scholar could predict events years from his time). Another remarkable fact. Yevhen Sverstiuk recalls that when the Soviet government decided to celebrate the millennium of the baptism of Rus’ in 1988, Braichevsky was the only historian and expert on religion who can professionally handle the issue. He wrote the book The Assertion of Christianity in Rus’ which would attract Pope John Pole II’s keen interest.

At the end of his career Mykhailo Braichevsky was a lecturer in the Kyiv Mohyla Academy and developed a course in history and philosophy, entitled “Introduction to the Historical Science.” He campaigned for the strengthening and development of Ukraine and the official status of Ukrainian. No wonder, he never received a single government award during his lifetime. Can one expect an award from a state that actually doesn’t exist? Such awards are an exception rather than rule.

Newspaper output №:

№38, (2011)Section

Ukraina Incognita