A road to Mykolaichuk

How will Ukraine mark the anniversary of its poetic cinema knight in 2011? <I>The Day</I> suggests starting right away

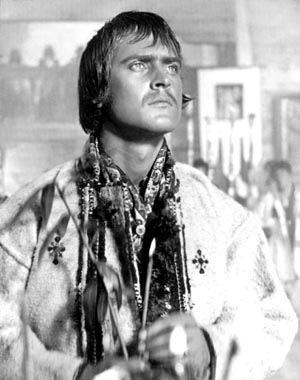

The 70th anniversary of the birth of the legendary actor, film director and playwright Ivan Mykolaichuk (June 15, 1941 – August 3, 1987) is a reason to recall important Ukrainian achievements. Mykolaichuk entered world cinema history owing to the film Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors — a record breaker in terms of the number of film festival awards. He became a symbol for an entire generation of Ukrainians who cared about their nation’s culture and soul. However, many compatriots ignore the full breadth of Mykolaichuk’s versatile talent, a challenge for his admirers and followers.

“The whole Ukraine is going to mark Mykolaichuk’s anniversary. The main venues of the events will be the capital Kyiv, theatrical Lviv, melodious Chernivtsi, and Mykolaichuk’s native village of Chortoryia in Bukovyna,” says Serhii Trymbach, cinema expert and head of the National Society of Cinematographers. “The anniversary events will include the publication of a DVD collection of films created with the participation of Mykolaichuk; an international festival of mythical-poetic cinema in Chernivtsi; the launching of an ‘Ivan Mykolaichuk’ website in Ukrainian, Russian, and English; retrospective screenings, book and photo exhibits, publishing and launching books about the artist, scholarly conferences etc. The organizing committee encourages all those who cares about Mykolaichuk’s memory, his art and Ukrainian culture in general, to participate in these events, launch their own actions, bring in interesting modern initiatives that would reveal the true scale of this notable figure. The anniversary year is approaching fast.”

The Day was among the first to join the actions and invites its readers on a tour to the village Chortoryia, held by the artist’s sister Frozyna Hrytsiuk.

Next year actor Mykolaichuk would have celebrated his 70th birthday. Unfortunately, he died long ago, on August 3, 1987. His name is known in many corners of the planet, but there is a tiny spot on Ukraine’s map, a village in the Kitsman raion of Bukovyna with a somewhat frightening name, Chortoryia. Here, in his father’s old house covered with straw, the Mykolaichuks’ fourth child out of ten was born. His life continued in that same wooden house with poor roofing. Here, in his father’s house, owing to the efforts of the talented movie actor, director and playwright and with the assistance of the local authorities a memorial house-museum was created in 1991. There is another, nice-looking modern building standing in the yard that Mykolaichuk built. He hoped to live there or spend summers, like in a summer cottage. He did not manage. Now the house belongs to his brother, but he left it to work elsewhere. So everything stands locked and quiet, as if Mykolaichuk has just left it for a short while — as if he has gone to the field, or the famous Chortoryia lake and its swans.

The transparent air rings with freshness. Here and there one can see yellow autumn leaves in the trees, the leaves lying in the ground are covered with new snow. The sun is warming, weeding out the frosty breathe of nature, and its tender rays turn into reflected light spots moving on the face of a bronze Mykolaichuk, who sadly observes what is going on in his yard near his native house, in the street that has been named after him. Could he hope for this? He is looking joyfully as frequently the doors of his house open to welcome the guests. People come from everywhere, even abroad. On the whole, the museum’s guest book bears commentaries by visitors from 18 different countries.

Sometimes there are several tours a day. They are held by the person who might have known Mykolaichuk the best and loved him the most: his sister Frozyna Hrytsiuk. She is already 80, but this petite tender woman has so much energy, warmth and good will! You start admiring her immediately when she starts to speak about her brother.

She opens the wooden doors to the house: there are two horse-shoes hanging next to it, to bring happiness and to protect the house. There is a small corridor and two rooms, to the left and to the right. The walls are densely covered with photos. Mykolaichuk’s portraits are like icons hanging next to their religious peers. Photos feature scenes from the films, work episodes; Ivan with friends, family, his wife Marichka; relaxing, at film festivals, in theater plays. There are also posters of Mykolaichuk’s films. Everything in the house is preserved as it used to be. There is kitchenware on the stove, fluffy blankets and home-made mats on the benches. On the handmade wooden shelves painted in blue there are simple family utensils: painted plates, cups, a clock — brought by Mykolaichuk for his sister from Georgia. On the floor, not far from the stove lies a unique item: Mykolaichuk’s cradle. And on the bench nearby there is an object of now less value: a self-portrait by Serhii Parajanov. It is hard to overestimate the value of one more item, Vasyl Stefanyk’s shirt, which the writer gave to Mykolaichuk as a souvenir.

Mykolaichuk brought photos from everywhere – from shooting locations, trips and meetings. There were so many of them that he had to take special luggage. When asked by his family about them, he joked: “It is for the museum.” Did he foresee it? Now they are of use. One can trace the moments of the actor’s life and creative work with the help of this huge and valuable photo archive. The museum has an extremely democratic atmosphere. The visitors are allowed to do everything. One can sit on a bench (where Mykolaichuk liked to sit), touch anything and look everywhere. There are no bans, only the benevolence is radiated by the keeper and guide. This trait is common to all the Mykolaichuk family, hence the origins of Mykolaichuk’s character and temperament. The artist’s photos with movie scenes are given to the tourists as a souvenir. In other museums they would have been sold, but Frozyna would never think of it. In her opinion all visitors should have a photo of her handsome brother as a souvenir.

Frozyna is very glad to see guests who come to Chortoryia, but sometimes she wonders: How do they know about the house? She has especially remembered the delegation of children aged between 12 and 14 who came from some far place. She asked in surprise, what should I tell you about Mykolaichuk? You might not remember and know Mykolaichuk. One boy replied, “If we did not know, we would not have arrived.” What to say? One should rejoice at this knowledge.

“Ivan was a handsome boy too,” Frozyna explains, “He studied for four years in Chortoryia’s school, and went to the neighboring village Barbivtsi for the seventh year. He studied the eighth year in a gymnasium in the raion center, Vashkivtsi. His gymnasium teacher liked him very much. Later she collected everything about Ivan: his films, cutouts from newspapers and magazines. She made an album about his life and gave it to the museum as a present on the 60th anniversary of his birth.

“Why did he like the movies? He saw a movie for the first time at the age of 13. I remember him saying, ‘I have wanted to do many things as a child, but I could not and I did not have to, and thanks to the cinema everything I dreamed about has come true.’ In our remote village Ivan developed a feeling of patriotism and kept it through his entire life — he cared about all things Ukrainian. His greatest dream was to make the world know about Bukovyna and Ukraine. And he did everything possible for this. Proof of this is the fact that A White Bird with a Black Mark is among world’s 10 best films. Ivan loved his native village very deeply. If he had problems, if anything went bad, he left everything, came to Chortoryia and recovered here. On the whole, he came home frequently. Many films were shot here — Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, A White Bird…, Annychka. Ivan engaged us also in his films. I remember, when he wrote the script for A White Bird..., he gathered all of his family in the house: his brothers Dmytro and Kost were also present. He invited us to have a seat and read this script aloud. Incidentally, I had many remarks and told him about them. Ivan always consulted, listened carefully and did what he felt is best. He told us in respect: ‘You are my first and dearest audience.’

“You know, at first father did not treat Ivan’s profession seriously. But he later went to Chernivtsi to see the play Land in a theater with Ivan performing, and afterwards he said: ‘I’m a strong man. But even I creid when I watched it, then I understood what being an actor means.’ When father died, Ivan was shooting Annychka. He got a telegram and came in two days. Later he said that he remembered the state of pain at the funeral forever and used it in one scene of the film.

“When Ivan got acquainted with Marichka, he came to me. He said that he would bring a girl, he asked whether I liked her. I told him that she was beautiful, young and shy. Then we introduced her ro our Mom, and mother liked her as well. She sang beautifully. They had a nice family.

“These are embroidered portraits. Shevchenko, which sister Maria embroidered for Ivan when he played Kobzar. During his preparation for Ivan Franko’s role, she embroidered the Mason’s portrait for him. But Ivan never had time to play this role.

“He was ill for a long time. My son Mykhailo frequently went to Kyiv to see Ivan. The latter told him, ‘Be a man: don’t tell a word about me to grandmother and mother.’ And I did not understand anything and asked son, why Ivan did not come for so long. Later he told me how he visited Ivan not long before his death. Marichka was doing something in the kitchen, and Ivan said that he wanted to tell him what to do with what would be left after him. Mykhailo tried to stop him, he did not want to show that he knew his uncle was fading away. Ivan lowered his head and said, ‘You don’t want to listen to me.’ Now my son asks himself, why did he do so? What if I listened to him? In a short while we received a phone call: Ivan was dying. My husband Heorhii went there, entered the room, and Ivan asked him, ‘Yurko, where’s Frozyna?’ He could not believe it, he thought that we were somewhere nearby in the room, and never left him. He wanted to see us so much. He was very exhausted by the disease, he had even dried out. My husband helped to put him on the stretcher. He remembered Ivan’s last look for his whole life.

“Ivan’s friends often came here, to Chortoryia and said that they missed Ivan, his presence, his talent, and his cinema very much. But they complained that they had to bear this cross. I asked them, whether the cross was heavy. They replied that it was heavy because he was not there to support them. He would better be alive and do everything himself in the kind and talented manner he was capable of.

“Ivan’s was not a simple destiny, but it was a lucky one. He lived a short life, but he managed to achieve a lot, he left a lot after himself. He would always repeat: ‘Long life is not the main thing. Most important is what useful things you manage to do while you’re alive.’”

Frozyna can talk about Mykolaichuk endessly. As she recalls, she seems to come back to her young years, when everyone was alive and the museum’s small world seemed to grow, as it was inspired by the mighty energy of the artist who will for ever remain the creator and bard of poetic cinema.

When parting Frozyna confessed that she had a dream which she is going to put to life. She wants to build a small movie theater near the house-museum, where the guests and everyone willing could watch Mykolaichuk’s films. This would remind some of what they already know, whereas the young generation would see these films for the first time and learn about the brightest artist of Ukrainian cinema, and at the same time about his fellow, equally-talented actors. It would be interesting, and the chain of cultural heritage would not be broken. The idea is good and needed. I would like not only the Mykolaichuk family to be involved in its implementation, but the state as well. Then the road to Ivan would be percieved as a kind of spiritual path for Ukrainians to themselves.