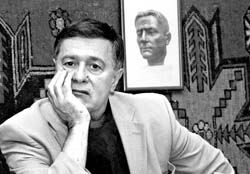

Roman Balaian turns 66

His <I>Flights</I> was released 25 years ago

On his birthday, April 15, director Roman Balaian began shooting a new film tentatively called The Chosen One , a wonderful boon to himself and the many film buffs who respect his work. He is not one of those who elbowed his way up, rushing to “fill the socialist order.” Balaian conveyed to the spectator his meditations on the classics. His filmography includes portraits of the subtlest psychologists of the human soul, Chekhov, Turgenev, and Leskov. When he turned to contemporary scripts, he created such a graphic portrayal of a disconcerted intellectual against the backdrop of our notorious everyday life that filmgoers, stunned to see the bitter truth, saw his films over and over again and then passed the baton to their children. The director’s latest movie, Night of Light , had a limited run because, luckily for audiences, it did not fit in with the newly established patterns of mainstream cinema but, instead, spoke in a simple language about eternal human values, such as the ability to sympathize. Kyiv’s oldest movie theater Zhovten will hold one screening only of Balaian’s famous hit Flights in Dreams and Reality in honor of Balaian’s birthday and the 25th anniversary of the release of this one-time cult film. Despite their busy schedules, the director will attend the screening with matinee idol Oleg Yankovsky, the film’s star. Balaian has never been a fan of hype or self-promotion. Out of principle he refuses to comment on current political events. However, he agreed to grant us an interview, and naturally our conversation touched on other topics besides the cinema.

Mr. Balaian, in the past theater and film directors would delve into the classics in order to avoid having to make epics about coal miners and steel-makers. They would adapt them to their times and use Aesopian language, relying on the spectator’s background knowledge and inner intuition. Spectators in turn were respectful of and boundlessly grateful to them for their trust. Today there is no censorship — everything is allowed. Why, then, the acute shortage of decent topics?

“The present day hasn’t asserted itself enough for one to be able to describe it in clear-cut analytical terms. Merely discussing current events is the preserve of columnists and politicians.”

I don’t mean politics. I’m saying that the classics are always current.

“No. The classics do not express contemporary times. Their domain is eternal values and ideas. And never, especially now, have they been a boon to the masses. Have you ever seen someone avidly reading Anna Karenina on the subway? For me, the classics have always been an opportunity to escape from expediency, the Soviet government, and its morality. But, funnily enough, there were wonderful, sincere, and highly artistic creations among what may be called flag- waving films about the communist system and the revolution, for example, Panfilov’s No Passage through the Fire or Mashchenko’s Commissars. These were made passionately, sincerely, and professionally. Incidentally, my guru Tymofii Levchuk was a card-holding communist to his last days. This is a moral position. The life stories of these kinds of people are much more understandable to me. This is what is known as true human dignity. He did believe, and it is not so important what he believed in. He was no chameleon and that inspires respect.”

A boy from the Karabakh region, who began to study in Yerevan, became a film director in Kyiv and known worldwide as a Ukrainian director. How did Roman Balaian become a Ukrainian film director, what brought him to Ukraine, and why does he consider Ukraine his second motherland?

“The boss of the Armenian film industry promised to transfer me to Moscow’s Institute of Cinematic Art if I succeeded in getting accepted to the Yerevan institute. I auditioned for the starring role in one of his films. Even though I failed, he and I developed a good relationship. I enrolled at the institute and began my studies.

When I was starting my third year, a woman appeared at the institute in search of ‘characteristic faces.’ I was one of them. We were taken high into the mountains. There were Russian and Ukrainian actors and directors there. They found it difficult to breathe at such an elevation. But one person was sitting quietly and guzzling glass after glass of Armenian cognac. He stood out from the others. By chance I found out that he was teaching a film direction course. That was Tymofii Levchuk. So I moved to Kyiv. Favoritism, you know (laughing ).”

Have you ever tried your hand at acting?

“Frankly, no, because in my very first year of studies I understood that the director is higher than an actor. It has never occurred to me. I can play better than any actor whom I have filmed just for 30 seconds or a minute, but if it is more than a minute, then of course I can’t. Like a violin, the actor is tuned for playing. I think that if actors play badly in my films, I am to blame. But I may be wrong.”

I have never heard a single actor complaining about Balaian the director. But I read somewhere that in the cinema the final result is just a tiny fraction of what was conceived, less than half.

“It depends. In my case, this is correct: 30 to 40 percent. That’s because of my nature. I like the concept, the script, and then the editing, when you don’t depend on technology, weather, or people’s moods. I didn’t succeed in entering the theater, where I could have realized myself better. I once staged a production at the Sovremennik Theater, but for a number of reasons it was not shown. But I liked it a lot: I am the boss, I am sitting at a table, there is tea or cognac disguised as tea; I go onstage and show something; tomorrow I change everything. What freedom! I am the king and the boss.”

When the new times came, why did it take you so long to make a film? Then you made two movies that once again did not fit in with the cinematic pattern - Two Moons, Three Suns and A Night of Light. This isn’t mainstream cinema, is it?”

“What’s so surprising? My films have never been popular with viewers. A box-office film is one that satisfies two-thirds of the audience. Sometimes I even saw spectators walking out of my film, and a lot of them.”

Is it realistic to make films for everyone?

“Yes. Look at The Godfather, the first film. There are films that don’t irritate either fools or academy members. In general, there are three categories of recognition: from audiences, critics, and peers. And no matter how hard you may look for subtexts and coding in my pictures, I have never had a true blockbuster.”

It is said that Flights prompted the famous linguist Lotman to write you a long letter.

“His first assistant sent me a long letter on his behalf, in which he sifted through every detail and line. Frankly speaking, I laughed when I read it. For example, in the final scene the hero is running across the field, the red soles of his sneakers flashing. ‘The earth is burning beneath his feet!’ he writes in ecstasy. But I remember scolding my props man for not finding me some normal footwear. I prefer other things, when, for example, spectators automatically compare themselves and their friends and family to film characters. This happened during a movie club debate on Flights.”

Can a director make both commercial and art house films?

“Yes, if he is an American director. The point is apparently in the school and the attitude to the process. Take Scorsese, for example. His movie Taxi Driver really amazed me. One day I was late for a preview at a cinema workshop in Bolshevo. A film was being shown, a good film. I laughed. It was nothing special, just a nice piece of professional work. I didn’t know who the director was. When the lights came on, the discussion began. Clever people were bubbling over with praise: the movie took their breath away. I tried to stem this tide of excitement, but they said in reply that it was Martin Scorsese! ‘Really?’ I asked in surprise. The film was New York, New York. Privately, I decided not to see his films any more and said this to Nikita Mikhalkov. After some time he brought a cassette of Raging Bull from the States and took great pains to make me watch it. That was astonishing! ‘How is this possible?’ I asked Mikhalkov in surprise. ‘He’s a professional, an old pro,’ Mikhalkov answered, laughing.”

You’ve been working for many years as the executive producer of TV serials. Why don’t you direct them serials?

“People make serials because they have nothing else to do. There is no cinema-making process and everything that goes with it. In my view, although I am not going to insult those who make them, serials are cheap pop art. Simply put, there are philharmonic concerts for the very few, and there are stadiums where you can hear loud, though not always bad, pop music, which I have nothing to do with. This is what I call a serial. I do not disparage them, but I personally would not make one.”

You are part of the national film-making process. Does it really exist? If so, what are its prospects?

“What is the difference between fundamental and applied science? Fundamental science deals with unpredictable things, so it gives you the right to make a mistake. Do we know any young film-makers? Perhaps only their teachers know them. When I was starting out, standing behind me were such masters as Paradzhanov, Levchuk, and Mashchenko. They gave me the right to make mistakes. Today, we should give a lot of young people the right to make a mistake. In Russia, for example, every third film is a debut.”

In this case, shouldn’t there be some kind of state program?

“Of course, but why not use our neighbors’ recipe? The more films being made the higher the likelihood of better quality 8 or 10 years later.”

In other words, let everyone who wants to make a debut? Isn’t this a waste of money?

“Yes. This is dipping into the cinematic pocket. If I had my way, I would definitely be giving public money exclusively to film debuts. This is the only way to ensure the future of our cinema. And teaching: if I were to launch a film directing course, I would be a manager instead of a teacher. But I would invite the best directors from all over the world to hold master classes and send boys and girls for advanced studies to every corner of the world. I think we have to drop our personal ambitions and biased approaches. The main thing is that we should stop reinventing the wheel all the time!”

The intellectual core of spectators has been greatly blunted by soap operas and the wave of high- tech blockbusters. Are there any prospects for art house films? Are they going to be in demand?

“Art house films have never been in demand, but they have always existed. Art cinema should either be subsidized by the state or thrown on the tender mercies of crazy art patrons. There is always a demand for auteur cinema because there is always a part of the population that lives a spiritual life that is different from ordinary people’s lives. All over the world, 70 percent of nations resemble each other a lot — not in terms of mentality but some other, psychological, features. And 30 percent are those who differ from each other. That’s my own theory, naive as it may sound.”

If you were asked to draw up a program to develop Ukrainian national cinema, what proposals would you make?

“I wouldn’t dare write one, but I would be glad to be a member of the team drafting this kind of program. First of all, the state has to be convinced that it needs the cinema as much as it needs unpolluted air. Look, when Mr. Putin was approached by film directors on whose films he was raised, he gave them 150 million dollars.”

Is there a professional cinematic community in Ukraine today, which is prepared to turn this huge amount to advantage?”

“There is one to devour it. But seriously, apparently nobody wants to see people capable of doing something useful. That’s a real pity! Fifty million hryvnias is a trifling amount for the Ukrainian budget, when billions are vanishing into thin air. We could mobilize young people and establish a totally new Ukrainian cinema as an industry. And to make it interesting outside Ukraine, you get into co-production. Maybe we should start with some kind of blockbuster.”

You are about to make a new movie that you’ve been thinking about for a long time. What kind of film is it? Why did you decide to shoot it in Ukraine? What is the language of the film?

“The script, written by Rustam Ibrahimbekov and me, is based on a story by Dmytro Savytsky. I first intended to make it with Russian money, but Kyiv producer Oleh Kokhan persuaded me to use Ukrainian funds. I don’t object as long as this country and the producer are providing the money. So far we have been using the producer’s money; the state hasn’t given its share. We have been waiting for a long time, since last fall. I won’t reveal the plot, but as the director, I am not indifferent to it. So it may become sort of a message to people. Pardon the high style. As for the language, it will be a bilingual film. Copies will be made in Ukrainian and Russian.”

Who are the actors?

“Oleg Yankovsky, Serhii Romaniuk, and a very interesting amateur actress named Oksana Akinshyna.”

She has been cast in so many films since Bodrov’s Sisters that she has become professional.”

“A professional actor implants what he or she has found, but she is still searching. The work will be difficult. I am used to actors sitting in place, nearby, when I am shooting. Oleg will come for five days, then again for a few days later in the summer. I will have to adjust myself to this.”

“Is the film’s bilingualism a tribute to the vogue?”

“No, this is pragmatism, for domestic and foreign consumption. Russia is a huge film market. And my readiness to make the film in Ukrainian stems from my firm conviction that a sovereign state should have single borders, a single army, and a single language. If a law had been passed in 1991, as I proposed, directing all the lower grades in schools to switch to the Ukrainian language within seven years, this language would be organic now for the majority of this country’s population and nobody would have to be re- taught by force. And maybe we wouldn’t be having the problems that we have today.”