The Price of Simple Things

The most ordinary things turn out to be the most complicated. Something we fail to notice, like the air we breathe or a clean bill of health, things which, when looked at closely, reveal a brain-twisting complexity of issues, considering all those multitudinous subtle works done by our organism. A jetliner looks simple and comfortable for the passenger just because so much sophisticated work has been put in it by the R&D team and manufacturer.

Largely, the same is true of public life. Daily routine in its simplest manifestations calls for events on a geological scale. Karl Marx wrote that it took several wars and revolutions for the occurrence of elementary things without which the bourgeois establishment could not exist, like a national market.

One may frequently complain of the lack of elementary things. Proceeding in this logical vein, however, leads one to the conclusion that the absence of these things is merely a signal indicating the absence of entire massifs, continents, components of wildlife (e.g., the absence of the platypus testifying to the absence of Australia, the animal's only natural habitat).

Sometime in the 1930s USSR People's Commissar of Education Lunacharsky was posed a rather naive question during a meeting with Soviet youth, namely what it took to become an intellectual. He said one had to be a graduate of three higher schools. This was followed by a shower of questions: What kind of higher school? Majoring in what? To this Comrade Lunacharsky replied, "It would take your father, grandfather, and yourself to graduate from such institutions of higher learning."

In other words, when asked how come there is so little by way of erudition or cultured attitudes in Ukraine, one may well answer that very few people had an opportunity to graduate from three higher schools.

Life really consists of simple necessary things. They are necessary, because they cannot be bypassed; they are simple, and consequently they cannot be simplified. One cannot live without thinking things over, meaning that clear thinking is necessary. The choice is simple: you are either clever or stupid. A simple thing, really (here simple does not mean primitive. In this sense being simple means that a certain thing is impossible to consider as made of a little of this and that, as being composed of so many even simpler things; just as a woman cannot be considered "somewhat pregnant").

But let us go further. The mind exists only in dialogue, in communication - i.e., in practice, just like courage, kindness, or any other human quality. It is impossible to remain kind doing nothing or be clever without getting involved in various forms of communication, whether scientific, political, or business. And when there is no advanced infrastructure (numerous computer networks, scientific conferences, periodicals, publishers, etc.), when free communications are cut short by administrative measures, when the very nutrient medium of intellect disappears. The natural consequence: this intellect disappears in a society as a phenomenon (e.g., brain drain).

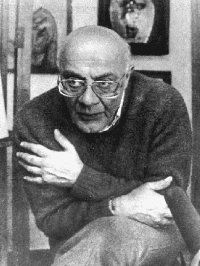

Merab Mamardashvili dealt with precisely such simple and inconspicuous links. The key paradox in his description of the situation existing in the country at the period was the allegation that there was nothing real about that society. Generally speaking, the very notion of reality shows that, if nothing living can exist, no live movement can come to pass; there are not any of those necessary and simple things; they do not work, meaning that there is no reality and neither could there have been any.

The philosopher's train of thought was simple, despite it being so paradoxical: justice, good, beauty, and love - things we hold precious but existing only in the presence of certain individuals, human beings translating these notions into practice. These things do not exist by themselves. For Good to exist someone has to do things generally considered good. If nobody does such things good cannot exist. The same applies to beauty and mercy. Such things can only occur in the world through human deeds. They cannot come about of their own free will. This is a universal rule. For example laws can work in a society only when there are people prepared to observe them. Likewise, a constitution is effective only when there are people willing to abide by it.

Let me note in passing that competent understanding of these fundamental things can be ascertained precisely by perceiving their linkage to a given individual with his/her own unique visage, the only one capable of keeping his actions under control. One of Academician Sakharov's friends said: "Quite recently a middle-aged scientist who knew Andrei Sakharov well told me that he still was not sure what the human rights movement had actually achieved in the USSR (Sakharov included). Indeed, they saved several persons, but this did not help solve any of the global problems. This concept is widespread, testimony to a complete lack to understanding Sakharov and his civil, primarily moral stand. On more than one occasion I heard Mr. Sakharov say in a voice seemingly lacking confidence but in reality dotting the i's and crossing the t's: "I guess I really did save his life."

Here an extremely strict rule is at play, the true understanding of "great things" like God, Truth, and one's native land. How can someone who does not love his brother love a God that he cannot see? In other words, if one does not appreciate or fails to perceive the value of one's fellow human beings, however talented or inimitable he is, one cannot be expected to perceive the true value of the things one seems to be struggling for, for these things can exist only through a given individual fighting for or against them.

In other words, there is an unbreakable link between all those simple things necessary for us and the individual, unbreakable because if there is no person there are no such things. Without being an individual, one cannot act according to the dictates of one's conscience, just as one cannot show genuine mercy or perceive of things truly beautiful. Without such things life becomes meaningless and we can see as much with our own eyes. Mamardashvili would say: "Let's take the revolutionizing perestroika campaign. Is it really irreversible? I do not know. I know only the way to make it irreversible. Irreversibility is something only man can do. This takes individual points of irreversibility and it is important to know precisely how many such points actually exist and against which any counteraction will inevitably result in disintegration and ruination. Now these are the values to compose any mathematically valid integral.

What I am driving at is that we will not be able to locate enough personalities jealously keeping their name clean and their products good, making them into all those "simple necessary things."

How can we increase the quantity of such things? (One is instantly aware of all those urgent or top priority measures, building up individuality, the good old Soviet officialese effectively surviving all political changes in this country.) Yet a question posed must be answered, and this answer is like the one about the intelligentsia. Let me tell you about a tourist looking at a beautiful flower-bed in a British park. The tourist was obviously a man of means and wanted to know how he could have a similar lawn at his estate. The answer was: plant grass and such-and-such herbs, water them every day, trim, and two hundred years later you are likely to have an exact replica.

Certainly, individuality can develop under any conditions. But to make it the rule, not exception, a given society must have forces of long duration and sufficient influence to foster the process. Take the notion of private ownership. It still hurts many domestic ears, sounding more like theft than private business. In reality private property is the very basis upon which rests every individual. It is a fool-proof system warding off any unwelcome influence from without. In the eighteenth century British Prime Minister William Pitt declared that a pauper living in his miserable makeshift home had the right to resist the Crown. The house can collapse, the roof can be shook, the wind can whistle in every corner or collapse under a storm, giving way to cold rain, yet the British king cannot step into this home, for all his power does not give him the right to cross the threshold of this miserable abode.

It is understandable that when such forces giving the citizen independent support are at work in a society for generations to come, other absolutely different individuals emerge who are absent in any other society without such underlying principles. Mamardashvili recalled history, about how in that same eighteenth century Prussian King Frederick, finding a nearby mill marring his view of landscape, wanted to have it torn down. The peasant owning the mill refused to part with his property. The king threatened him with confiscation, to which the peasant replied that there were judges in Prussia. The monarch liked the answer so much he ordered the text carved on one of the porticos of his summer retreat.

Such forms as private property arise and work naturally as a separate species. By the same token man cannot do anything to act instead of earth, yielding wheat, because earth has to do this itself, unaided. Likewise, it is impossible to replace any effects produced by certain forms on public life, the market, for example, being one such form. It is not simply a way to exchange goods but a certain information device, a gamble on supply and demand producing certain ratios and costs. The price becomes known to us (the market seems to inform us about it), it is our knowledge; and at the same time it is a fact: such-and-such a ratio has been established. Here knowledge does not exist separate from hard fact. We cannot find out the price without the market, without a definite supply and demand ratio.

To explain evidence and simultaneously illustrate the paradoxicality of such devices, I will cite other example. Ukrainian political scientist Mykola Tomenko, analyzing the results of the last parliamentary elections in Ukraine, stressing that they dispelled some myths, in particular the one about the general aspiration for a union with Russia, says that two blocks, Elephant and Union openly declaring their Russia union program guidelines, collected a miserable number of votes.

The special character of such devices in this case is well seen: knowledge that can be received only by a natural power play (in this case by casting votes). The elections give us some knowledge, in other words acting as an information vehicle. Simultaneously, elections establish a concrete fact which is made public. Prior to the elections such knowledge was not available (instead, there was a certain myth, says Mr. Tomenko). We received this knowledge only as a result of the elections, but this knowledge emerged only with the fact of elections, when a certain situation was established by the elections as fact.

This knowledge cannot exist before certain vehicles (elections or markets) are activated. But after activating them another fact emerges, being evidence, knowledge that can neither be refuted nor abolished. Such facts have the structure of human actions: if you play fair, then this fair approach will have manifested itself in your acts, requiring no comment, as a talented picture requires no caption: acts (yours and someone elses) can teach a better lesson than any explanations.

Working with the help of such devices, a given society lives and simultaneously learns itself. These devices create something best described as a lingua franca, understandable to one and all, included in this common activity (actually, here we have an ideal example of the res publica, Latin for republic, that makes it possible for us to understand and cooperate with each other. An individual acting independently of others nevertheless works in the same vein, and in millions of cases there appears an inadvertent cooperation, as with the customer and worker example cited above.

If man is not included in these processes he is denied this regularized status; man simply does not understand the nature and mechanism/vehicle of such life - as was the case with that rich young man whose father demanded that he learn to earn a living while his mother, pitying her son, gave him money which he showed his father, claiming it had been earned. Suspicious, his father threw the money in the fire and the young man watched it indifferently.

Today's Ukrainian society resembles this young man in many respects; it has received democratic institutions rather than earned them (as is the case with most other former Soviet republics). It still has to learn how to use them. So far things often happen the way a French journalist queried the philosopher about, back in 1990:

"The general impression is that events in Germany meet with complete indifference in your country. How would you explain this phenomenon?"

"You are right," Mamardashvili replied. "For one to be interested in such developments one has to live in Europe, not geographically of course; I mean within the European lifestyle. Europe is concerned about this issue because its settlement will have a strong impact on the Europe's lifestyle and opportunities as a whole. For us the whole thing is as remote as the idea of life on Mars. We may have a common language, but we live on different planets in this sense."

"Yet we often hear you say that you are part of Europe. How is that?"

"Now this one is a very serious phenomenon in our inner life, because we do not actually have a common language and concept of the realities. In this sense the difference between you and us is reconstructed. We use your language, but our reality does not correspond to the reality of your language.

"Usually, the head and body are of the same origin, and the information passing from the brain to the rest of the organism is constantly in a homogeneous environment. Let's make a metaphorical assumption: the head (where everything occurring to the body is perceived) and body are of differ origin. This is precisely what happens in our Soviet and Russian cases.

"It is necessary to be a part of the reality to show an interest in it. Words allow us to address mentally what is going on in Germany, but there no communication with the reality. Hence, it is normal to show no interest in the German issue.

"Thus, we again come back to the problem of the absence of reality. Certain things are impossible to simulate. For example, it is possible to present students their diplomas the very next day after they enroll, but this will not change the actual situation. Any operations of signification have a limit beyond which they are faced with physical reality. Remember that story about a parrot? The woman who kept it bragged about the clever bird talking to her friend, saying, 'See? There are two threads tied to its legs; the white one tied to the left leg and the red one to the right leg. I pull the white one and the parrot says hello and when I pull the red one he says goodbye.' 'Suppose you pull both, what would happen?," asks her friend, to which the parrot replies, 'Don't be silly, I would be knocked off my feet.'

"Once again, without special vehicles, special institutions such as elections, market, where hard facts are naturally ascertained (meaning a new reality and knowledge about it), all those simple things without which society and nation do not exist are impossible. Take the notion of generation. It would also be impossible; we speak about youth and use words like generation and tradition, but this usage is illegitimate. For these notions to make sense and have any effect on public self-consciousness, the physical presence of young people and their problems is insufficient. It takes a linkage binding them all (precisely that which formal organizations and information make impossible to exist), converging in a certain space in which people could openly display themselves and their problems, and in which they could be aware of themselves as a 'generation' capable of being that very organ developing real problems and situations (take elections in Ukraine: self-awareness and, say, of orientations, is born only in the definite space of elections - author). In actuality, one idea is separated from the next by thousands of kilometers (say, between a young man in Riga and one in Vladivostok, or in Luhansk and Lviv - author), and every such idea atomized from all others. As a result: these ideas seem to exist, yet they do not. And the fact some external observer may actually translate these ideas into life does not really matter."

Here we see that phenomena of such literature, cinematography, and the press are the vehicles necessary for the existence of a nation. Literature is not just so many books published (just as cinematography is not just so many films released); it is a vehicle for bringing forth and discussing certain problems. While there is practically no film-making in Ukraine, the press is practically regional, as the print run of even the most popular newspapers is more often than not in the neighborhood of several tens of thousands, and this with the populace registering fifty million. This means that talking of a Ukrainian nation is premature (one could be reminded of the fact that none of the political parties and blocs received the required minimum of votes in all regions during the last parliamentary elections).

The problem here is not only - and not primarily - connected with financing. These vehicles are in an as dilapidated condition as, say, the market. Note that a lot of discussions closely followed by the press never yielded any original ideas. But, in the words of Merab Mamardashvili, poetastery is a manner of writing that has nothing creative about it.

Institutions such as literature, theater, and cinema are necessary, in order to raise and discuss certain issues of general importance. Without them it would be impossible even to comprehend the scope of any such problems; this is something impossible to achieve in with small talk at a party or over a bottle with your neighbor in your kitchen, with the rest of the family sleeping; this takes too much argumentation. And how is one to solve a problem never actually seen or identified? Calling a spade a spade is not that easy, it turns out.

In one of his last interviews, asked whether people's mentality had changed after all those Gulag death camps, Merab Mamardashvili said:

"It changed only where certain efforts were being made, where many books had been written and publicly discussed. Unfortunately, very little if anything has been done in this country of late. And unless something tangible is done in this direction we will not learn that bitter lesson and our self-consciousness will not change.

"This can be done only publicly. Culture is public by definition. There can be no underground culture, in the sense that such culture is barren. Everything stews in its own juices. Here backwater provinciality and elusiveness are inevitable; everything is either past history or vague prospects. Nothing in the present. And all our significant pauses and meaningful hems and haws have strictly 'internal value,' something we understand but which is Greek to everyone else; we can hold whispered discussions and seem to accept it as our genuine culture. It is not. Culture is inherently meant to exist in the open, visible and accessible to all. Well, this cannot be helped, for such is the nature of culture. Thus, we need people with talent and ideas begotten previously and kept secret because of the existing regime, now allowed to speak and act in the open. The more we have such people, the greater will be our accomplishment. This will give us ground for the next step. We will perceive what has actually happened to us and why, what it proves, and is to be expected from it.

"I must say that something has been accomplished in Western culture. Maybe not as much as there should have been but a step has been made toward digesting everything that we have experienced. I mean Nazism."

"So what has actually happened to that consciousness in which all this was perceived?"

"I'm not sure. It seems that European culture has made a repetition of Nazism impossible. I am strongly reminded of the so-called Moscow trial, intended as an analog of the Nuremberg one with regard to Communism. It never happened and the public interest it attracted was about the same as that shown in what happened in Germany. This could be evidence that we are still to reach the point of no return."

In another interview things were mentioned being very close to Ukraine, even geographically:

Do you think that Chornobyl has taught us a lesson?"

"I don't think so, barring fragmentary expert opinions that we hear now and then. And this after all that Herculean self-denial being done there As for a handful of facts meant to make the situation clear, that is, The Bell of Chornobyl, facts are intermingled with lies and vague statements, all drowning in a lot of static. Particularly because the crux of the matter is clear: Chornobyl is publicly recognized as a place to exploit, where a pyramid will be erected, higher than that of the Sun. I was stunned to hear all this on television and read it in newspapers. A trap for the very idea and all those wishing to take certain active steps. And the result? Thousands of half-truths that will entangle, forming a vicious circle, and no one will ever find out the truth."

Mamardashvili frequently addressed the language problem. How can one make heads or tails of a phrase like "the country's vegetable conveyer," he asked. One instantly pictures hefty guys with shovels, and it is absolutely impossible to imagine how the vegetables fit into the picture. One finds oneself in a certain force field, being launched by a certain programmed trajectory. Or how can a living idea, or living feeling, for example, a mother mourning the death of her son, be expressed by the notion of "soldier-internationalist" (the Soviet propaganda clichО for those who took part in the Afghan War)?

All this testifies to a problem which was topical under the Soviets and has remained: creating an autonomy of thought, a "literary republic," a living language which could emerge in the course of lively and responsible discourse, a language one could speak and understand, rather than collapse as a thinking living being. This sphere is the same device as the market or elections: a certain fact emerged which simultaneously became knowledge. Here, too, a language emerges making it possible to think; at the same time people included in the space of this language exist differently. But then consider the passionate desire for social knowledge that existed in the USSR and is still there, remember Raikin, Vysotsky, Zhvanetsky, all those Soviet pop idols of the 1960s-1980s. They all carried social charge, an element of creativity. An all those political jokes and anecdotes!

Mental labor more often than not is where one finds a way out of the deadlock. Even an idiot (i.e., "zero variant" of cognition, destroying all things best and sacred, which cannot help him simply because he is a fool: a fool can never do anything right) who is miraculously aware of his lacking in the upper story (i.e., being able to affirm a well-known fact for himself) is, actually, no longer a fool.

Mental work, of course, embraces all spheres of life; thinking is possible and necessary at all times, under all circumstances. In fact, the notion of industry implies a purposeful well though-through process, not just so many plants and factories. Just like a logical train of thought cannot retain integrity if a single link is removed, by the same token an industry cannot exist unless properly balanced, manned, and equipped. Otherwise, considering the universal rule whereby simple things require a sophisticated approach, such trite notions as meat, butter, bread, hot, even cold running water tend to become extinct. So why mourn the platypus in Australia?

It is possible to say of any present thinker that his/her accomplishment

cannot be possibly exhausted, that this thinker forever remains a living

and genuine interlocutor. This, in turn, keeps us all alive. Thus spoke

Mamardashvili: "If I am thinking of something at the moment, this means

that Kant is alive in my thought; this also means that I exist. On the

othe hand, if I exist, this means that Kant is alive." In fact, the Georgian

philosopher remains our active interlocutor, so we can live abiding by

the dictates of common decency. Thinking must be made a simple little thing

like civility, so we can say of our thinking that nothing is given us so

cheap and appreciated so dearly afterward. Civility is not as simple as

its face value: Being able to say thank you a manner befitting a given

situation is one of those "simple things," yet an art unto itself, one

of the pillars supporting this sinful world, rooted in the mist of millennia.

Newspaper output №:

№3, (1999)Section

Personality