A symbol of Ukrainian tenacity

Borys Ten: an underappreciated classic

The 110th anniversary of the birth of Mykola Khomychevsky, who is more familiar to readers by his pseudonym Borys Ten (1897—1983), was in December 2007. Unfortunately, just like his centenary, this anniversary went practically unnoticed. A few events were held in the places associated with this extraordinary person. A one-room museum was opened in the local school in his native village of Derman. That’s all well and good, but Ten deserves much more, and any self-respecting nation should honor a person of his caliber in a different way.

He was, without exaggeration, a titan and had a simply fantastic life. The son of an Orthodox priest, he managed to survive Stalin’s GULAGs and Nazi concentration camps. Without breaking under pressure, he worked in horrible conditions and made a lasting contribution to Ukrainian culture. In a certain sense, Ten is a symbol of Ukrainian tenacity, vitality, and industriousness.

Derman is known for its enduring cultural traditions. One of the largest and most ancient Orthodox monasteries in Volhynia, founded by the princely Ostrozky family, was once located there. A constellation of prominent activists are associated with Derman and its monastery, including Ivan Fedorovych, Meletii Smotrytsky, Iov Kniahynytsky, and others. The village produced such notable figures as Ulas Samchuk, one of the finest prose writers of 20th-century Ukrainian literature.

Ten’s mother was also born in Derman, into the family of a local priest named Ivanytsky. This was a highly educated family, which was fond of literature, music, and theater, and these tendencies can be observed in Ten’s own life. His father, the son of a priest, was born in the Kovel area. Before graduating from the Volyn Theological Seminary, he was appointed the village priest in Kunyn, near Derman.

Ten’s childhood and adolescent years were spent in Kunyn and Derman, where he attended school and studied classical and modern languages. In 1913 his parents moved to Zhytomyr. In 1917 he got his first job, and in 1918 he enrolled in a branch of the Institute of Public Education (INO), which had opened in Zhytomyr.

In 1920 Ten became actively involved in the movement to establish the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (UAPTs) and was one of the main organizers of the Zhytomyr branch of this church. He also played an important role in the First Volhynian Congress of the UAPTs in 1923. He was ordained a priest that same year and experienced the first persecutions carried out by the Soviet authorities. He was not permitted to defend his diploma paper at the institute and left without a diploma. Ten was arrested in connection with the Bishop Stefan Orlyk case and sentenced to six months’ probation.

At this time Ten began actively participating in cultural life. He published his first poems under the pseudonym Borys Ten (derived from Borysten, the ancient name of the Dnipro River). He began working on Ukrainian translations of the ancient classics and cooperated with the Independent Theater in Zhytomyr.

In 1924 he moved to Kyiv, where he held the position of archdeacon at St. Sophia’s Cathedral and was elected second deputy- head of the All-Ukrainian Orthodox Church Council. Ten was instrumental in the cultural development of the UAPTs and its transformation into a truly national religious institution.

In Kyiv he developed close ties with the Neoclassicist poets, including Mykola Zerov and Maksym Rylsky. He did various editorial and translation jobs for the Knyhospilka and Siaivo publishing houses and the State Publishing House of Ukraine. He translated texts for the vocal repertoire of the Kyiv Philharmonic Society, the opera theater, the Dumka Choir, and the Lysenko Institute of Music and Drama.

When the persecution of the UAPTs leadership began in July 1926, Ten was forced to find new employment. He moved from St. Sophia’s Cathedral to St. Paul’s Church in the Podil district without slowing down his ecclesiastical- cultural activity. In 1927 he began publishing articles, literary translations, and religious poems in the journal Tserkva i zhyttia (Church and Life), founded by the UAPTs. He also tried to improve church services by making them more theatrical and closer to Ukrainian national traditions.

In 1929 Ten was arrested during the trial of the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine (SVU). He was accused of pursuing “the church line in the SVU” and sentenced to 10 years in forced labor camps.

He was sent to the Far East, where he got married. His wife, Apollinaria (Nara) Kovalchuk, a graduate of the Lysenko Institute whom he had met in Kyiv, joined him in 1931. One can only marvel at this woman’s courage.

In 1936 Ten was given an early release, but he was unable to return to Ukraine. He lived in the Far East for a while, eventually moving to Kalinin, where he worked in a theater and as the director of several music groups.

During World War II he was mobilized into the Red Army. His unit was encircled and he was taken prisoner by the Nazis. He was first moved to Novhorod-Siversky, where he was nearly shot. Finally, he ended up in a camp in the city of Langenbielau in Silesia. Even though Ten had a good command of German, he did not use his knowledge in captivity. He made use of it when Soviet troops entered Langenbielau. People who had been imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps were generally regarded as traitors and sent to Soviet concentration camps in Siberia. Ten’s knowledge of German stood him in good stead, as the Germans employed him as a translator in the commandant’s office.

In late 1945 he finally returned to Zhytomyr. However, he had no right to live in the city and for a while was forced to reside in the countryside. Later, he worked at the Zhytomyr Pedagogical Institute and was in charge of amateur performances. He also worked in a music college and taught Latin at the Zhytomyr Foreign Languages Institute. His last position was that of a lecturer in the Zhytomyr Arts College.

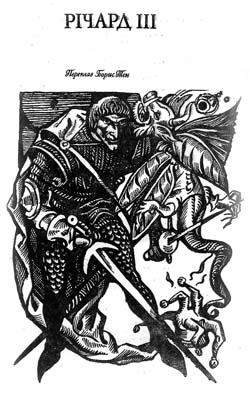

During the postwar period Ten focused on Ukrainian translations of world classics, above all, Greek classical literature. He translated Greek dramas, the plays of William Shakespeare, and Polish poets. But his real feat was his translations of the Illiad and the Odyssey on which he worked for many years. His excellent knowledge of Greek and masterly command of Ukrainian lent unsurpassable quality to these translations. To this day they are considered the finest Slavic translations of Homer.

Although Ten’s work was highly appreciated in Ukraine and abroad, the Soviet authorities tried to trip him up even in his declining years. His “dark past” caught up with him and he was often the target of envy. Although he was nominated, he did not receive the Shevchenko State Prize. He was finally awarded the Rylsky Prize for his translations only in his eighties. There were also problems with his translations of the Illiad and Odyssey, which were published in a relatively small press run.

In his last years Ten, who belonged to the Writers’ Union of the USSR, made a considerable contribution to the development of the Zhytomyr branch of this literary organization and the city’s cultural life in general. Without him the phenomenon of the so-called Zhytomyr School would not have emerged in Ukrainian literature.

All this provides more than enough grounds to state that Ten is one of the most prominent representatives of Ukrainian culture. But Ukraine is a strange country: Ten is still underappreciated in our independent state. His heritage, which acquaints us with the finest examples of world culture and introduces us to perfect Ukrainian, is not in demand today. Since independence, we have learned to speak fine words about spiritual revival and suchlike. Yet virtually nothing has been done to restore the heritage of this colossus to Ukrainians. His unique works remain virtually unknown to most people, and his translations are hard to find even in our largest libraries. Like most of Ten’s translations of the ancient classics, the Ukrainian translations of the Illiad and the Odyssey have not been reprinted in independent Ukraine. But Russian translations of ancient Greek works, which are clearly inferior to Ten’s achievements, are used in Ukraine. There is no need even to mention Ten’s musical heritage and the complete study of his work, which is still lacking in Ukraine.

This is indeed a sad state of affairs.

Petro Kraliuk is the vice-rector of National University of Ostroh Academy.