Good, Old, Finnish

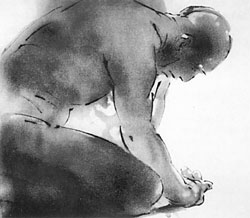

The exposition of Modern Finnish Graphic Arts at the Lavra Gallery leaves one with the impression of a conservative oasis. Plenty of light, no humming equipment repeating fragments of monotonous phantasms labeled Installation, no photo posters on the walls to hit one in the head with their images. The Finns are largely pensive, reserved in colors, and they obviously know their own worth. All things considered, they are really in no hurry to catch up with the mainland in terms of avant-garde bathos. They are content to watch nature, trying to catch some very subtle nuances of moods. Yet their conservatism (as well as modernistic endeavors) are not an end in itself but merely a way to achieve truly beautiful results. Eeva-Liisa Isomaa, with her ascetic nonfigurative manner, could be classified with the abstractionists. Yet the fuzzy spots on her prints gather to form powerful force fields born of nature, begetting impressive images of glaciers, ocean surf, rock, and snowcaps. On the other hand, Anita Jensen (incidentally, another curious phenomenon in Finnish art, with female artists playing an extremely important role) in her Confidential Souvenirs composes clearly articulated photo montages in which things purely human and natural join with the inevitability of a nightmare: human faces, fragments of plants, a burned tree. The line of a torn, twisted world is given extreme development in Jari Kylli Delirium. Here symbols from all fields of knowledge race in an inexorable merry-go-round. For example, several compositions by Antti Tanttu are titled Martyr, although they are quite harmless phantoms against the background of a world library; here one need not suffer, but meditate. Buddhist thoughtfulness permeates Kirsi Tiittanen’s cycle, Places for Silence. In fact, most Finnish graphic artists are on this side of life. Annu Vertanen and Harri Lepp К nen lithographs are saturated with childishly bright impressions. One wants to pause in front of Ann Sundholm’s Catalogue and touch those fantastic books-cum-cots with precisely the toys one lacked in one’s youth displayed on the front cover in lieu of a title. Likewise, Maria Str Ъ mmer turns into toys her meticulously painted Forests by gluing a ready etching onto a cube of real wood. However, the styling center of the entire exposition are Jucho Karjalajnen’s outwardly low-key prints offering male figures bent or sitting. They have unerring contours, richly expressive, bursting with passion and solitude: a man looking at his hand, a man standing on the ground, a man and a fish, a silent planet. These works and this artist must be discussed using such very strong and simple categories. Whether his art is typically Finnish or typically international is unimportant. It is simply thus governed by the Muses, Apollo or whatever other unknown guardians of artistic inspiration there might be. Things can be created to be very effective, even shocking. And things can be created very simply, yet with a much greater depth than the most fantastic, incredible forms and techniques. Perhaps this is something the Finns could teach the world.