Pyotr Todorovsky: “We have not repented yet”

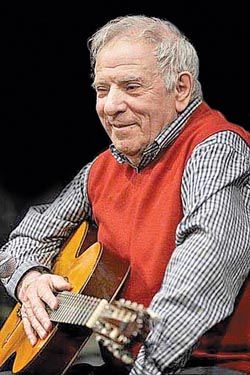

In the sonorous and frosty Khanty-Mansiysk Pyotr Todorovsky headed an international jury. As in his artistic work, which included stints as a cameraman, actor, film director, composer, and musician-performer of his own songs, he managed to find time to watch movies, socialize with colleagues, have fun, and perform with a guitar on stage.

Pyotr was born in 1925, meaning he endured the full cruelty of the war. Pyotr Todorovsky spent the entire war as an infantryman. He then entered the All-Union State Institute of Cinematography (VGIK), the workshop of Boris Volchek, and became a cameraman. One of his works is the famous Vesna na Zarechnoy ulitse (Spring on Zarechnaya Street). In 1965 he made his debut as a film director. Vernost (Faithfulness), Voyenno-polevoy roman (Military-field Romance), Ankor, yeshchio ankor! (Encore, Encore Again!), Fokusnik (The Magician), Rio Rita, and Liubimaya zhenshchina mekhanika Gavrilova (The Mechanic Gavrilov’s Beloved Woman), are just a part of his filmography. Our countryman by birthplace and Odesa citizen by vocation, he continues to work fruitfully and to “relish life,” celebrating his 80th anniversary five years ago.

Mr. Todorovsky, cinema today has ceased to be the mass didactic phenomenon it was in the 20th century. How has the language of cinema changed?

“Twenty years after the collapse of the Soviet Union everything changed so drastically that sometimes it’s even difficult to comment it on. A new generation, raised under absolutely different conditions, has appeared. They have been submerged by a huge stream of information, and were able to say what they think without the inteference of editors or censorship. The aim is money! But this is a very difficult issue. Especially right now, as cinema hasn’t been financed for almost a year now. Only serials are produced, which are ‘swallowed’ by television channels. Naturally, they mostly lack good taste, a sense of tact, and are not distinguished by professionalism. It corrupts the audience which is stuck to television screens. Of course, it doesn’t concern the young spectator, but for them there is another ‘chewing gum.’ The film School by Gay Germanika is currently being shown. It is expected to receive a ‘Golden Eagle.’ In an interview with Germanika, she confessed that she came to ‘school’ from porno. Our generation was different, censorship pressed upon us so hard that even today the self-editor continues working inside.”

And yet you were able to convey such a feeling of freedom in your films...

“You know, my films, as well as the best films of the Soviet cinematography – Letiat zhuravli (Cranes are Flying), Balada pro soldata (A Ballad about a Soldier) and others, they appeared after Stalin’s death. Hryhorii Chukhrai, Marlen Khutsiev, and Mikhail Shveitser appeared. They created great movies. The current youth in cinema revises our life, our films. I do not mean this in a bad way.”

Do you feel it in relations with your son, who followed in your footsteps?

“You see, Valera is a quite different person, a free person. I was constrained.”

In my opinion, you always made an impression of a very free person.

“I somehow had the chance not to produce conjuncture films, and could do what I wanted. It’s not usual when a director can do that. The exception was the film based on the play Posledniaya zhertva (The Last Victim) by Aleksandr Ostrovsky. It is not my kind of stuff, though both the playwright and the play are great. The films like Faithfulness, Gorodskoy romans (Urban Romance), The Magician and others are my type of stuff.”

You’re from the generation of directors who didn’t shoot battle scenes, glorified marshals or victorious generals, but talked about the war in ordinary people’s lives.

“In fact, I didn’t shoot films about the war, but talked about people during the war. I like telling stories: distinct, recognizable. I’m created like this and I can’t shoot avant-garde. I believe that within 5-10 minutes after the beginning of a film the spectator must forget that he or she is watching a movie, they must emotionally penetrate the life of the characters and not think about the idea of the film. But if in a day or two they will return to this story, that is when they will develop their own ideas.”

How did you and your generation survive the difficult historical and political cataclysms with dignity. How did you manage to spiritually preserve yourself?

“Because of my naivety. I just shot what I wanted; I felt that was what I was supposed to do. Sometimes I betrayed myself. For example, I worked at the Odesa Studio and then moved to Moscow. To get to ‘Mosfilm’ was a lucky break. The films I previously mentioned were behind me, and I was put in charge of several classics. I did them, and only after that I was taken to the staff of the main film studio in the country.”

But you started as a cameraman?

“Yes, I worked on the film Spring on Zarechnaya Street. Many good and cheerful memories are connected with this period of my life. However, being a cameraman, I had to do sketches about the war all the time. I worked with great film directors. Once a great opportunity came along: a director, who just graduated from VGIK, was inexperienced, so I was appointed the chief cameraman and co-director. It was a film about a man who devoted himself to work. He ended up alone, without friends, his wife left him and so did his dog. It was a movie about loneliness. That’s how I had a first taste of this wonderful profession. The point is in telling actors and explaining to them what you expect from them.”

You worked with great actors, and sometimes even discovered them. How did that happen?

“I was lucky, I worked with such actors as Yevgenii Leonov, Inna Churikova (I already knew she was the heroine of the Military-field Romance), hot-tempered, passionate Natasha Andreichenko, as well as Oleg Borisov – an actor of genius. When I invited him for the central role in the film Po glavnoy ulitse s orkestrom (Down the Main Street with Orchestra), I couldn’t even imagine he could be so tender and sensitive. And Elena Yakovleva – a very talented and modest person, without star fever. She’s like a workhorse. When we were shooting Interdevochka (International Girl), we were accorded 22 days for the work in Stockholm. And no one cared whether we would be able to make it in this time or not. It was very difficult. Shootings for 12 hours a day, and she was in the epicenter! Moreover, she was running temperatures of around 39 degrees. There was also Liuda Gurchenko, with whom I returned to Odesa in order to shoot The Mechanic Gavrilov’s Beloved Woman. Many other people could be mentioned. And of course, there is Ziamochka Gerdt. We were friends for 30 years, and had great communication! So interesting! About life, poetry, and everything else. He was an endless source of inspiration. So many amazing stories are connected with him! He was always young. His love of life overcame everything – age, illness etc. Even when he was in a very bad shape, and was brought to a performance (it was his last performance on stage) in the Children’s Theater. His wife Tania was sitting next to him with a syringe in her hand. Yet he found the strength to get up, make a few steps and do an unforgettable reading of the poems by David Samoylov. I lost a lot with his death. In recent years we communicated every day. Our dachas, where we lived, were very close to each other.”

How did the relations with people back then vary from current ones?

“The generation which experienced the war was purer, more naive, and grumbled less. We just wanted to do our job. Before us there was a generation that didn’t do anything in cinema. Many people disappeared. And we were lucky – the terrible dictator passed away. There were many opportunities ahead of us, and we were glad! This generation is quite different. They want to participate in festivals, get prizes. We made films and didn’t think about money. For example, when we were shooting Dva Fiodora (Two Fedors), we ran out of film strip in the middle of the movie, and we paid for it from our salaries. However, they are freer than we were, both their hands and tongue are freed. It would be good to learn how to use them.”

We will soon celebrate the 65th anniversary of Victory Day. Every year there are less people who survived the war. The young generation doesn’t know history at all, and in Russia Stalin is put on a pedestal, they call him an “efficient manager.” Luzhkov said that he wants to hang portraits of the bloody dictator together with quotes referring to his role in the victory. How do you evaluate all this?

“As being idiotic. Regarding this issue, of course, our authorities should seriously think through every step so that it doesn’t fuel up unnecessary hatred. One shouldn’t manipulate the feelings and memories of people. Astafyev once wrote in Tri pisma generalam (Three Letters to Generals) that the more we lied about the war, the nearer we drew the next one. There was a great book by Gavriil Popov, the first post-war mayor of Moscow. In every chapter he appealed to tell the truth about the war, about the great Victory and the great Defeat. Germans show television shows all the time, in which they uncover the bones of those who perished in Treblinka and other terrible war crimes. This is repentance, and we haven’t repented yet!”

Let’s return to the origins, the beginning of your work, what are your best memories from Odesa?

“Oh, that’s a wonderful city! I’ll tell you two anecdotes, stories which happened to me right after my arrival there. I had flown in during the night in order to start working as a cameraman on the movie Spring on Zarechnaya Street. I got on a tram in the morning and went to the studio. The tram was half-empty, I sat close to the driver, and someone pushed his head into the driver’s cabin asking about the condition of the tram’s brake and how safe the trip was. ‘Does your brake work well?’ – ‘Sure it does!’ – ‘Try it!’ – the carriage stopped abruptly. – ‘Okay. Please open the door, this is where I get out.’

A few days later I was walking around Odesa, getting acquainted with the city. I stopped to drink some water. I finally bought some from a stout, succulent Odesa woman. I gave her 20 kopecks and asked for a glass of pure water. While drinking she kept looking at me with kind, motherly eyes. My mute question was answered with a sorrowful voice: ‘But it seems to me I won’t give you the change.’ – ‘Why?’ – ‘I recognize you, you broke my glass yesterday!’ What could I possibly say!?”

How often do you visit Odesa?

“I visit it very often. There is a great mayor who invites us for City Day on May 9. Odesa is flourishing. All the buildings in the downtown are renovated; amazing cafes can be found, and there are beautiful monuments. The only thing spoiling the impression is the destruction and sale of the Odesa Film Studio, which, in fact, doesn’t exist anymore. A disaster!”

Your last film Rio Rita emerges only at rare festival screenings. It was shot about three years ago, have you had any opportunities to work since then?

“What opportunity can there be, if there is no money, if cinema is not financed. It’s not clear what will happen next. Mikhalkov suggested a new scheme of money division – take money from the State Cinema and give them to a certain foundation which will finance big companies. They, in turn, will create blockbusters. This is wrong and will lead to the collapse of national cinematography. This scheme is almost approved, though it seems suspended at the moment. But for how long?”

And what do you like in today’s cinema?

“Well, first of all, I like what my son is doing. His movie Stiliagi deserved the prizes it won – the ‘Nika’ in particular.

In this film Valerii made an elegant stylization of that period, but the events there are from the time of your youth. How well did he capture that period?

“I respect him very much for undertaking and successfully creating the difficult genre of movie – a musical. And just remember how accurately the film conveys the atmosphere of a communal apartment! I also like how Dima Meskhiyev works – Svoi (Ours), from the point of view of direction, is wonderfully done. I like Aleksei Balabanov, although not everything. Gruz 200 (Load 200) is definitely too much, but he swears he personally saw everything. And my colleague from the jury at this festival Larisa Sadilova works in a very interesting way. She tells people’s stories skillfully and accurately. Here I watched her new work Synok (Sonny). Very worthy. I absolutely don’t accept avant-garde cinema. I was once asked about my opinion on it. I answered that every time I woke up I understood it was brilliant.”

What do awards mean in your life?

“I do not get over-excited about them. I see it as a moment of self-admiration, something like self-assertion. One can live without them, but it looks like you can’t refuse them either. For example, I got three orders of Merit for the Fatherland, of the fourth, the third and the second degree. After the second degree my pension was increased.”

If someone agreed to finance whatever you wanted, what would you like to shoot?

“At present I am a bit too old to shoot a big production film. But I can still make chamber movies. I have a few scripts, and I can’t stay without work. One of them is called Portret, peyzazh and zhanrovaya stsena (Portrait, Landscape, and Genre Scene). Perhaps I could hand it over to my student, a debutant of this festival Masha Martynova (the competition film Pobud so mnoy [Stay with Me]). Especially since it’s a story about youth. Of course, if she may have other plans. The second one is about the first minutes after the war, Oglushennye tishynoy (Deafened by Silence). The third one is inspired by a walk in San Francisco, that we visited in a group. I wake up early, the first, so I went for a walk. I counted the places where one can have a meal. I saw an extremely pretty girl in the window, she was sitting half-faced towards me. She looked back and in an instant, as if taking a picture of me, evaluated me. It inspired the script Khudozhnik i prostitutka (Painter and Whore).”

Besides writing scripts, do you read other people’s work?

“Not that much now – I have problems with my sight. But I read Liudmila Ulitskaya with pleasure. Right now I am reading an autobiographical book by Vladimir Voinovich, also enjoying it.”

Where do you find the strength to shoot, write, communicate, and not get sick and tired of people?

“I’ve always been a light and joyful person. And on shooting area I always try to create a cheerful atmosphere. I’m an optimist by nature. I endure troubles with a smile. I discard all problems and disgusting things in order not to perish, out of self-preservation. It’s easy to be happy when you’re young; the point is to maintain this ability throughout life. I love life and ‘hope it is a mutual feeling.’”