False Dimitrii

The Ukrainian card in a Russian impostor’s game

At the very beginning of the 17th century tsarist Russia experienced a very difficult period, known as the Time of Troubles. This historical period is marked by the sudden rise of False Dimitrii I and his devastating failure. The facts provided in the following article prove that this impostor could have never attained such improbable victories without significant support from Ukraine.

SELF-STYLED TSAR

Yurii Bogdanovich Otrepev, the future impostor who pretended to be Ivan the Terrible’s son Dimitrii (officially recorded as having been murdered in May 1591), was born into the family of the strelets (rifleman) officer Bogdan Otrepev in Kolomna, a town outside Moscow. Later, Tsar Boris Godunov and his closest associates did much to discredit their enemy, portraying him as a talentless young fellow and a drinker who also practiced black magic. In reality, since his childhood Yurii Otrepev was a horse of a different color. He was by nature a gifted young individual with a precocious mind, an excellent memory, a keen ear for music, and diligence. Thanks to these qualities, the young Otrepev mastered grammar in record time, overtaking most of his peers.

As is often the case with such individuals, the powerful ambitions of this infantry officer’s son were equal to his obvious talents. At an early age he began considering ways of making his career, although his modest social background did not offer him a single chance in the Muscovite state. He finally decided to take advantage of a technique that is as old as the hills — by finding himself a powerful guardian. The future imposter spent some time working as a servant on Prince Cherkassky’s estate, and later at the estate of the well-known boyar Mikhail Romanov. This career-oriented young fellow knew what he was doing. At the time a number of Russians actually saw Romanov as a major claimant to the Russian throne.

According to some sources, Otrepev used his extraordinary skills in order to be singled out quickly from among the Romanov family’s royal servants. But all his hopes for assistance from the wealthy nobleman were destroyed one day in October 1600, when the estate was surrounded by a detachment of the tsar’s streltsy (someone reported to Tsar Godunov that Romanov was plotting an attempt on his life). The servants, including Otrepev, tried to defend their master, but they were outnumbered, and all were to be punished severely for resisting the tsar’s men. Bogdan Otrepev’s son, however, managed to avoid execution by becoming a monk and taking the name Grigorii.

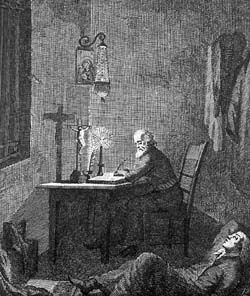

Romanov’s former servant made a spectacular career in the new spiritual field. It took him only a year to go from being a rank and file monk in Moscow’s Chudov Monastery to deacon and member of the patriarch’s retinue. One can only imagine what summits the young deacon could have reached if he had pursued his monastic career. He would have gone down in history not as one of Muscovy’s impostors but as an outstanding clergyman of the Russian Orthodox Church. As I will try to demonstrate in this article, his spectacular career was cut short by the monk Grigori’s intense and genuine interest in purely secular matters.

As soon as he became deacon, Otrepev started collecting facts and evidence relating to the tragedy of Uglich in 1591, with enviable scrupulousness. Once, the deacon surprised the rest of the Chudov monks by declaring that he would soon become the new tsar of Muscovy. The monks simply laughed at their young brother’s eccentricity. However, the situation in which Grigori found himself proved very serious, as rumors about a new claimant to the Russia throne soon reached the ears of the tsar. Fearing imminent arrest, Otrepev fled the elite Chudov Monastery, which had been the scene of one of his triumphs.

The former monk had two options. One meant that he would remain a fugitive monk for the rest of his life. The second was to implement the striking idea that no one at the monastery had taken seriously. Many people in Otrepev’s situation would choose the first option and be happy that the Lord had granted them another day of freedom and another piece of bread. But Grigorii should be given credit. He knew how to set tasks that were too ambitious for his age. Thus, he decided to proclaim himself Dimitrii, the son of Ivan the Terrible, who had avoided death and begun to struggle for his “father’s” throne.

SEARCH FOR PROTECTORS

Otrepev was too clever for his age and quickly realized that all his “royal” ambitions would remain shining youthful dreams without support from powerful individuals. The question was where to find them. The impostor understood quickly enough that such support was practically impossible in Muscovy, where Boris Godunov ruled with an iron hand, crushing any kind of opposition. “Tsarevich Dimitrii” decided to try to find it in the neighboring Polish kingdom, the Rzezcpospolita.

One day Otrepev and two monks from Chudov, Varlaam and Mikhail, set off on the long journey and eventually arrived in Siverian Ukraine. Grigorii and his traveling companions spent several days at the Monastery of the Holy Trinity and St. Sergius in Novhorod-Siversky and then continued their trip. Several hours after their departure the abbot discovered a note to the effect that none other than Tsarevich Dimitrii, who had miraculously escaped death, had visited the monastery.

Of course, in terms of basic conspiracy this was a careless move on the part of the fugitive monk. There could be hardliners at the monastery, who unquestioningly supported Boris Godunov and who would quickly deduce the identity of the author of that note and neutralize him once and for all. Yet from the human standpoint his move is perfectly understandable: he was eager to feel himself in the role of tsar, which he had invented.

Some time later Grigorii and his companions reached Chernihiv and then Kyiv. The three monks immediately visited the Kyivan Cave Monastery, where they stayed for about three weeks. Toward the end of his visit Otrepev spoke to the abbot and told him who he really was.

I think that this move on the part of False Dimitrii should be interpreted as the beginning of his search for powerful protectors. He thought that the Orthodox Church in the Rzeczpospolita could well become one of them. However, the response he received at the Cave Monastery was a bitter disappointment. No one took the ambitious young man seriously and he was shown the door. But he refused to give up. Indeed, he could not have acted otherwise because the fugitive monk was a very persistent man, firmly resolved to find a powerful patron. He soon parted company with his two companions, and this was not coincidental either. Both of them knew his secrets and could seriously damage his cause. Soon afterward False Dimitrii appeared in Osten, the estate of Prince Konstantyn Ostrozky. But the “tsarevich” never received support from the powerful magnate, who simply ordered his servants to show him the way out.

It is difficult to say exactly how many failures befell the man who claimed to be Ivan the Terrible’s son. There were probably many and each was a sharp blow to his ambitions. Like an actor who has learned his part well, Otrepev now profoundly identified with his role as the tsar’s son. But the cruel realities often reminded the unfrocked monk of his true identity: a commoner who could be humiliated with impunity. It is also true, however, that Otrepev was recognized as tsarevich by the heretical Arian sect, and the impostor spent some time at the Arian school in Hoshcha. He eventually abandoned the Arians after belatedly realizing that he would never ascend to Muscovy’s throne as a heretical tsar.

It is anyone’s guess what course the impostor’s destiny would have taken if he had not appeared one day in Brachyn, the Poltava estate of the Polish prince and magnate Adam Wisniowiecki, where he asked for a servant’s job. He was taken into the household and eventually revealed his secret to his master. According to one story, Wisniowiecki became so enraged at his servant that he struck him hard in the face. In response, the offended Otrepev proudly told Wisniowiecki that his master had hit Ivan the Terrible’s son. Several minutes later the “tsar’s son” told the prince his legend: that some people devoted to him had learned that an attempt on the tsarevich’s life was being prepared and had replaced him with another boy, who bore a striking resemblance to him and had died a violent death instead of him.

Finally the fugitive monk and impostor achieved something for which he had long been waiting. Wisniowiecki unquestioningly recognized him as the tsar’s son Dimitrii and ordered his many servants to treat him with the respect due a tsar. Before long the false tsarevich and his protector began seriously considering the possibility of a military campaign against Muscovy to help the impostor attain the throne.

It is difficult to say with any certainty whether Prince Wisniowiecki believed Otrepev’s story. Quite possibly he did not because False Dimitrii’s story about the faithful retainers knowing in advance about the attempt on his life is highly unlikely. According to historians, the preparations for the attempt on his life were a closely kept secret. By and large, the prince did not care if the man was really Ivan the Terrible’s son or a typical impostor, one of many in world history. Nevertheless, Wisniowiecki acknowledged the impostor and promised him military assistance. In doing so, he was thinking primarily of his own interests. The prince’s large estates, which were located in an unstable border area, were often caught in the middle of armed encounters between the magnate’s and tsarist troops. Wisniowiecki seriously expected that once his protege attained the Russian throne, he would immediately secure his protector’s peaceful and stable feudal reign.

As it was, the military campaign that Prince Wisniowiecki was enthusiastically preparing was destined to end without ever having begun. The magnate’s troops were greatly outnumbered and did not suffice for a serious military campaign. Assistance from the Crimean khan did not arrive, despite Wisniowiecki’s letter to the khan asking for help. As a result, the Polish magnate’s interest in the False Dimitrii’s campaign quickly cooled, which forced the fugitive monk to change his orientation. His luck held out this time too, and Otrepev’s new protector — not the last figure to appear on the political horizon of the Polish Kingdom — became Jerzy Mniszech, a Polish senator, the voivode of Sandomierz, and the starosta of Lviv and Sambir.

FROM LVIV TO KYIV

Mniszech accorded the visiting impostor a royal welcome. Without a doubt, this attitude was warranted by his personal interests. At one time Mniszech had succeeded in being appointed manager of several Polish royal estates that produced large annual revenues for the royal treasury. Mniszech shamelessly pocketed a large part of this money while endlessly delaying payments to the treasury. Finally, high-ranking officials told the senator that he had two choices: to stop such practices once and for all or much of his property would be confiscated to cover his debt.

Mniszech placed even bigger hopes in False Dimitrii than Wisniowiecki. With his assistance, the old embezzler of public funds expected not only to erase his huge debts, but also increase his financial situation. Mniszech suggested that the impostor marry his daughter Marina and give her one million rubles from the tsar’s treasury, and the right to rule the lands of Novgorod and Pskov. For his part, Mniszech undertook to wage a military campaign against Boris Godunov, after organizing a meeting between the impostor and King Sigismund of Poland. During the meeting Otrepev unofficially agreed to add the Chernihiv-Siversky territory to the Polish kingdom in return for the Rzeczpospolita’s assistance with his accession to the Muscovite throne.

Volodymyr Horak is a historian .

(To be continued)