Against the common enemy

Little-known pages in the history of anti-Bolshevik alliances in Ukraine in 1918-21

Soviet historians claimed that one of the main causes of the final victory of the Russian Bolsheviks in the 1918-21 Civil War was the acute differences in the large and diversified anti-Bolshevik camp. I share this opinion because various anti-Soviet forces often fought with each other no less stubbornly and cruelly than they did with the communists. However, it should be kept in mind that many “counterrevolutionary” leaders were perfectly aware of the necessity to join forces in the struggle against the Red enemy and took concrete steps in this direction.

HETMAN SKOROPADSKY AND THE WHITE ARMY: FROM MUTUAL ANIMOSITY TO UNITED ACTIONS

A characteristic feature of the Civil War in both Russia and Ukraine was the emergence on the territory of the former Russian Empire of a large number of states with different social systems: Bolshevik Russia, the Ukrainian Hetmanate, Menshevik Georgia, Dashnat-ruled Armenia, Southern Russia (the territory administered by the White Army generals Kornilov, Denikin, and Wrangel), and several others.

A comparative analysis of the social orders in Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky’s Ukrainian state and the White-Army-ruled Southern Russia shows that they had many features in common. Both Skoropadsky and the White generals were mostly oriented towards the pre-Revolutionary social system: they restored private ownership, returned estates to landowners, and suppressed all manifestations of popular opposition. With regard to social changes, they usually positioned themselves as moderate reformers of the Russian pre-Revolutionary economic order. Thus, it would seem that the Ukrainian and Russian conservative states were supposed to cooperate closely with each other, all the more so as they faced the threat of Bolshevism, a common and by no means weak enemy. What stood in their leaders’ way was a different understanding of common Russian prospects. While General Denikin’s government firmly adhered to the idea of a “single and undivided Russia,” for a long period of time the Skoropadsky administration tried to establish an independent Ukrainian state. Denikin’s White Guard officers explicitly refused to recognize Ukrainian independence and called the hetman a separatist and a traitor. The impression was that if they had succeeded in routing the Bolsheviks, they would have made short work of “breakaway Ukraine.” It is a proven fact that Skoropadsky himself was not exactly rushing to give official recognition to Southern Russia.

Yet it would be wrong to claim that there were no positive relations between the two states during this period. In many cities of the Ukrainian hetmanate (Kyiv, Kharkiv, Poltava, Odesa, etc.) there were many practically legal organizations (so-called bureaus) that were recruiting officers to various White armies — Volunteer, Southern, Astrakhan, and others. (The Volunteer Army was republican, while the three others were openly monarchist.) Although in the summer of 1918 the hetman’s government strictly forbade local officers to join Denikin’s army, many officers who had formally signed up for monarchist armed formations in fact made their way to General Denikin’s army on which they were pinning their greatest hopes.

A rather peculiar situation emerged. Although the commanders of the Volunteer Army refused to give official recognition to the Hetmanate, the latter in fact turned into a “supplier” of career officers for that army and other White formations, which very much resembled an alliance, albeit an unofficial and one-sided one. In my opinion, Skoropadsky had his own calculations. On the one hand, the hetman was getting rid of the most active White Army elements (which together with the left-wing opposition represented a definite danger to his state) while on the other, he was reinforcing the White movement in order to tighten as much as possible the knot of the bloody struggle between the Reds and the Whites, which could considerably weaken the Ukrainian state’s overt and covert enemies.

The situation in the Ukrainian Hetmanate took a turn for the worse in October-November 1918. Following the revolutions in Germany and Austria-Hungary, the hetman’s government lost its most reliable armed support — the Austro-German army. The hetman’s armed forces were comparatively small and politically unreliable as well, while the fear of drawing overtly revolutionary elements into the army prevented Skoropadsky from issuing a general mobilization. As a result, the hetman could only really count on the help of Denikin’s Volunteer Army and the Entente troops. Representatives of Denikin and the Entente did not rule out the prospect of providing the Ukrainian state with military and other types of assistance, but they demanded that the hetman’s government officially drop its pro-independence stand.

Skoropadsky made a strenuous effort to forge a serious alliance with the Whites. In mid-November 1918 the hetman issued a decree establishing a new goal for his country: a struggle for a federated non- Bolshevik Russia. Approximately at the same time a new hetman government headed by Serhii Herbel was formed, and almost all of its ministers were oriented toward the revival of a “great Russia.” The hetman told some leading figures of the Volunteer Army in Kyiv — clearly out of tactical considerations — that he had never been a true advocate of Ukrainian independence.

It was no accident that the post of commander-in-chief of the Ukrainian armed forces was assigned to General Fedor Keller, a convinced Russian monarchist. In early November 1918 Skoropadsky met Otaman Krasnov, leader of the White movement in the Don River region, and told him that he had a concrete plan to unite the armed forces of various non- Bolshevik states. Quite tellingly, the hetman wanted to see the Grand Prince Nikolai Nikolaevich, brother of the executed Emperor Nicholas II, in the post of commander-in-chief of the future united army, and he personally wrote to him in this connection. In Kyiv the generals Sviatopolk-Mirsky, Rubanov, and others began hectically forming the so-called officers’ militia consisting of staunch supporters of the “White cause.” Skoropadsky also issued an order to form a Special Corps answerable to him personally. The following detail is a graphic illustration of whom the hetman wished to see in the corps: the servicemen of his “personal” unit wore the old tsarist, not Ukrainian, uniform.

Finally, the hetman’s Foreign Minister Afanasiev officially informed Denikin that from that moment the Ukrainian army would be fighting for the restoration of “great Russia” in alliance with the Volunteer Army and the White troops of the Don. In reply, the commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces of Southern Russia officially agreed to cooperate closely with the Hetmanate and supported Skoropadsky’s intention to form a united anti-Bolshevik army.

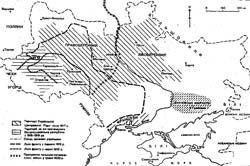

This plan never came to fruition, not in the least because of the precipitous collapse of the Hetmanate in mid-December 1918. There are also facts proving that the hetman and the White Army began to forge a military alliance in the first three weeks of December 1918. During meetings of the hetman government on Nov. 29 and Dec. 7 it was decided to invite the Volunteer Army and Don White Cossack units to the Kharkiv and Katerynoslav regions with the aim of fighting against “domestic Bolsheviks.” Indeed, the golden-epauletted allied units soon appeared in Ukraine. One of them was the 2,000- strong 8th White Army Corps formed in Katerynoslav with the Hetmanate’s consent.

There is no doubt that this state of affairs somewhat increased the Ukrainian state’s chances for survival. However, there was also a downside to this alliance. Some White Army officers, both within Ukraine and outside its borders, thought that Ukraine could no longer be considered a state. The Ukrainian press published Denikin’s order subordinating the hetman’s officers to the Volunteer Army. General Keller then officially proclaimed the restoration of the Russian Empire. Some “vested interests” strongly advised the hetman and his ministers to raise the Volunteer Army’s flag over Kyiv. In some places there were riots of White Army elements, during which supporters of an independent Ukraine were arrested and busts of Taras Shevchenko were smashed. Skoropadsky was forced to cool the hottest White Army heads. Keller was relieved of his duties as commander-in-chief, and General Lomnovsky, a representative of the Volunteer Army, was arrested.

Clearly, the hetman took a great risk in resorting to these strong-arm measures. The supporters of the Russian tricolor could have made an adequate rebuttal, all the more so as a considerable number of Skoropadsky’s soldiers openly spoke about their subordination to Denikin’s military command. But Symon Petliura’s revolutionary army was already stationed near the entrance to Kyiv, and a face-off between the White Army and the hetman’s forces would have been a real disaster for both.

White Army units made an indisputable contribution to defending the Ukrainian state from the “domestic Bolsheviks.” On Nov. 18, 1918, White Army troops and Serdiuk regiments waged a fierce battle near Motovylivka with Petliura’s approaching units, defeating them on Nov. 21, 1918. This delayed Petliura’s advance to Kyiv by more than half a month. But the comparatively small White Army units could not save the hetman’s government from catastrophe in a situation in which the majority of the Ukrainian populace was overtly hostile to the hetman’s rule.

AN ALLIANCE OF THE WHITE ARMY AMD PETLIURA: THE FUTILITY OF GREAT EXPECTATIONS

Petliura’s army, which toppled the hetman’s regime in December 1918, had no time for a long-awaited rest. Almost immediately the Petliurites engaged their new enemies, including the White Army “volunteers,” who were also laying claim to power in Ukraine. The struggle was short-lasting. After signing a truce with the Entente, the Petliurites stopped fighting against its ally — Denikin’s army. Later, in August 1919, units led by Petliura’s commander Yurko Tiutiunnyk again clashed with White Army troops near the Khrystynivka railway station.

Volodymyr Horak is a Candidate of Sciences in History.

(To be concluded in the next issue of Ukraina Incognita)