Politicians, scientists, and journalists from 92 countries checked their bearings

The weekend before last Vienna hosted an international conference, Morality and Politics, organized by Project Syndicate together with Vienna Institute of Human Sciences. The list of speakers is really impressing: in addition to such outstanding political figures as President of the European Commission Romano Prodi, Federal Chancellor of Austria Wolfgang SchЯssel, President of Poland Aleksander Kwasniewski, Great Britain’s Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer Michael Howard, President of the Polish National Bank and former prime minister of Poland Leszek Balcerowicz, there were also renowned economists, sociologists, political scientists: professor of economics Joseph Stiglitz, president of the Open Society Institute Aryeh Neier, professor of politics at the Prinston University Amy Gutmann, professor of European thought at the London School of Economics John Gray, professor and chair of European civilization at the College of Europe and former Polish minister of foreign affairs Bronislaw Geremek, et. al. Many names in this far from complete list are well known to The Day’s readers: they often appear in our newspaper under the articles presented by Project Syndicate. It was exactly representatives of quality newspapers throughout the world (including one from The Day) who constituted the majority of the Vienna conference’s participants.

Project Syndicate is an international newspaper association existing since 1994. Unlike a classic newspaper syndicate, it doesn’t consist of some central newspaper and a number of its branches throughout the world but unites equal partners among which there are both monsters of world press like Le Figaro and Le Monde (France), Der Standard (Austria), Die Welt and Handelsblatt (Germany), Guardian (Great Britain), Corriere della Sera (Italy) and newspapers which are less popular in the world and with more modest circulation, but still quality and professional ones. Let’s look at the figures: at present the association unites 170 newspapers from 92 countries with a total pressrun of 29 million copies. Since spring 1999 our newspaper joined this project, becoming first member of the Syndicate in Ukraine and among first in the CIS. Membership in Project Syndicate is a quality mark of a kind, an evidence that the newspaper’s level corresponds to global tendencies in presenting information, its participation in the global political and analytic discourse. Precisely owing to Syndicate The Day’s readers have an opportunity to read simultaneously with their counterparts from 90 countries comments and analytical articles on global events and tendencies, written by renowned scholars and politicians specially for Project Syndicate.

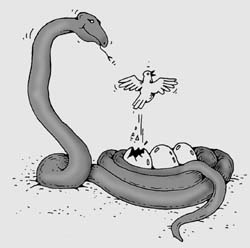

The conference’s title, Morality and Politics, can be perceived by many, to put it mildly, with certain skepticism, since for the majority of people politics and morality are incompatible. The conference’s organizers suggested a quotation from Immanuel Kant as a keynote, “Politics says, “Be ye wise as serpents”; morality adds, as a limiting condition, “and guileless as doves.” If these two injunctions are incompatible in a single command, then politics and morality are really in conflict; but if these two qualities ought always to be united, the thought of contrariety is absurd, and the question as to how the conflict between morals and politics is to be resolved cannot even be posed as a problem.” It was the question of the compatibility of these notions that the conference’s participants tried to resolve at the three sessions devoted to the topics, “Moral Obligations and the International Economic Order,” “Moral Sources and Moral Limits of Democracy,” and “Morality and Foreign Policy.” “A Set of Ethics for Europe” — such was the subject of a keynote speech delivered by President of the European Commission Romano Prodi at the opening of the conference. Instead of reading out his speech, the printed version of which has been distributed among the participants (“It wasn’t worth coming to Vienna” to do only this, he noted), Mr. Prodi made a few observations on moral and ethical problems the European Union is facing. In his words, though the European Union does not have any power to regulate ethical matters directly, it can play an important role in signposting the way forward, establishing the parameters of debate, and promoting dialog. Both at his press conference and in his speech president of the European Commission repeatedly stressed that though “the ethical principles that inspired our Union... have won the hearts and minds of European countries that are not yet members,” who “now want to join us and slowly but surely adopt our values and objectives,” the Union “cannot enlarge on end,” and doesn’t see its future as an “ever increasing body (so that our citizens lose their identity that unites them).” Speaking specifically about the probability of Ukraine and Russia’s entering the EU, Mr. Prodi said that it would be premature to speak about it at least until their economic indices improve.

Another keynote speech was delivered by President of Poland Aleksander Kwasniewski. Its subject, “Is Honest Politics Possible?”, sounds rather global. However, the Polish president spoke about more concrete things, namely, his view of an honest and dishonest politician. In president Kwasniewski’s opinion, a politician is dishonest if he is “fanatic, inflexible (i.e. sure that he’s absolutely right),” no matter whether he is characterized by “a cynical form of pragmatism” or is “naive and utopian.” To the contrary, an honest politician “regards politics as a tool to achieve common good,” devotes himself to “day and everyday activities” without missing the final goal. He knows the “principles he’ll never sacrifice, the human rights and respect for Constitution” and is prepared to defend them. “A politician who wants to be efficient can’t afford to be dishonest. He’ll win only if people trust him,” the president concluded.

Probably the most interesting was the discussion of the topic, “Moral Obligations and the International Economic Order.” Two of the speakers, Lesek Balcerowicz and Joseph Stiglitz, represented the opposite viewpoints on the role and aftereffects of the activities of the international financial institutions. The former adheres to the opinion that their role in fighting poverty is only positive, while the governments of Burma, North Korea, or Cuba “prefer to starve their people rather than go to them” for support. And even if there are certain negative moments, it is not those institutions to blame but corrupt governments of the countries who receive the loans from them. Mr. Balcerowicz believes that the theory of the rich countries’ responsibility for the poverty is “false,” and the reason for such poverty lays in their bad location (Kyrgyzstan), wars (Sudan), and most of all in the so-called statism, meaning excessive state intervention in the fields where it could do no good, closed economy, over-regulation, and corruption. At the same time, the state is unable “to do its duties: secure law and order.”

International financial institutions are “trying to sell policies in the advantage of one groups and against the others,” believes Nobel Laureate in Economics Joseph Stiglitz. For instance, as a result of the Uruguay agreements on reducing import duties, incomes in Africa declined 2%. More than 100% subsidies to US farmers lead to increasing production and, consequently, lower prices, meaning that African farmers lose more money than all the aids the US gives to their countries. Often loans given by IMF to certain countries do no good to their people who, however, have to carry the heavy duty of paying them out later, Mr. Stiglitz said. He gave the examples of the financial aid to Zimbabwe dictator Mobutu or the loan given by IMF in 1998 to Russia, on the eve of the default (“Obviously, there was no chance that [this money] will help; it only helped oligarchs to get their money out of the country.”).

Ukrainian politicians were represented at the conference only in the person of Yuliya Tymoshenko. In her speech she insisted that in the last years the world has produced no spiritual leaders or projects for “global reconstruction,” i.e. utopias. Ms. Tymoshenko tried to fill in these gaps, proposing to lay morality “in the basement of the world order,” remove contradictions between state expediency and human freedoms. Interesting that, among other ideas suggested by Ms. Tymoshenko there was a proposal on “systemic demarcation between power and capital” and “separating mass media from both the power and capital.” In general, one should mark a rather good work of the BYuT leader’s PR men and speechwriters, especially taking into account that foreign audience is not so well acquainted with most of Ukrainian politicians’ business and political backgrounds.

How to correlate morals with democracy and define people’s common interest, how moral or immoral can be the choice made by the majority — this was the subject of the conference’s second session. Professor of politics at the Prinston University Amy Gutmann demonstrated how public opinion can change on the example of the issue of death penalty in the US, where in many states the majority of population supports it, though in most European countries it’s viewed as barbarism. In Ms. Gutmann’s words, the public opinion became less favorable towards death penalty due to the publications in the press on innocent people who were executed.

As one would expect, the discussion of moral sources and moral limits of democracy can be summed up by a popular quotation from Winston Churchill, “Democracy is the worst form of government except for all those others that have been tried.” Besides, as Federal Chancellor of Austria Wolfgang SchЯssel noted, “There are so many checks and balances that people can always correct their choice.”

The last topic discussed was “Morality and Foreign Policy.” Moral values are not universal, believes Director-General for External and Politico-Military Affairs of the Council of Ministers of the EU Robert Cooper. Evaluating other people through the prism of our moral criteria, we create a dichotomy, “them” and “us,” making “them” untouchable, while pluralism does not imply imposing the notion of amorality on people who are not “us,” Mr. Cooper said, however, specifying that “there are limits to respect for traditions and pluralism,” and if, say, genocide is a part of some nation’s tradition, this doesn’t make it moral. However, in general, believes Mr. Cooper, an attempt to apply moral values to foreign policy makes communication and solving problems more complicated (thus, Mr. Cooper denounced the term, axis of evil, explaining that evil is a religious term, and “if you think something is evil you are to destroy it,” which makes war unrestrained), while “value-free tradition allows dialog.” Professor of European thought at the London School of Economics John Gray disagreed with him, saying that foreign policy shouldn’t be a “value-free zone.” In his words, to the contrary of Marx’s and Saint Simon’s predictions that religion will become privatized or even replaced with other ideologies, now we are witnessing the return of its role as a decisive force in the foreign policy and issues of war and peace.

Professor and chair of European civilization at the College of Europe and former Polish minister of foreign affairs Bronislaw Geremek spoke against the idea of “preventive war” against Iraq. He opined that in Iraq’s case it would be impossible to repeat the post-war Germany and Japan experience, since, unlike these collapsed countries, Iraq is “a modern Western state.”

Projection of liberal values worldwide shouldn’t be the goal of foreign policy, believes John Gray. A country’s interest is not constant; every country makes its choice, defining its interest in every specific case, and this is a moral choice.

The conference’s goal was hardly giving a final and single answer to the question, to what extent a politician can and should be guided in his decisions and actions by moral requirements and norms, and, in general, what moral norms there are in politics. However, an attempt to analyze and compare the views on morality and politics of both decision-makers and those who study the consequences of their decisions was rather fruitful. Besides, the Syndicate newspapers’ editors who came to Vienna from all over the world got a chance to communicate with each other and with Syndicate representatives, to discuss how the project could further develop, giving assistance to its members in broadening their capacities and getting closer to each other and the world. Therefore, a window to the world of international information standards, arguments, and discussions will be open for The Day’s readers, as it used to be.