Mykola Azarov tells about who lives well and sleeps soundly in Ukraine

The relations between taxpayers and tax collectors are always complicated in a transition society. There is often too much distrust on both sides, which proves an extra tax burden.

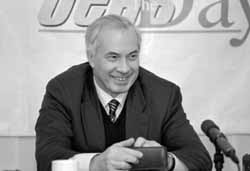

The Day has special reasons for presenting this sizable interview with Mykola Azarov, head of the State Tax Administration. There are very many taxpayers’ questions and this man cuts an especially interesting figure as a top government official and politician, whose role in the mounting election campaign can hardly be overstated.

“WE’LL HAVE THE LOWEST TAXES”

The Day: Russia is believed capable of making a serious economic breakthrough, considerably lowering the tax rates and instituting a single tax on individuals. What is there to prevent Ukraine from doing this? There was also a lot of criticism in Russia, addressing high taxes, and their Duma is markedly sharp-tongued.

Azarov: I can tell you quite frankly that our Verkhovna Rada is quite as sharp-tongued, but there is no way to compare things that aren’t comparable. The Russian and Ukrainian economies are essentially different. Russia has all the energy sources it needs, and this is one of the reasons the prime cost of its products is about three times lower than Ukraine’s. As during Soviet times, the Russian budget mainly relies on revenues from the extraction sectors — oil and gas, wood, and so on. We have no such sources.

In fact, Russia with its colossal might and financial resources is having very serious problems with budget revenue now that oil prices have fallen. True, they have a uniform personal income tax rate: 13%. We propose two rates, 10% and 20%, in the tax code bill. The former will be paid by practically 80% of the population, and the basic income tax rate will be lower than in Russia. The 20% rate will apply to the better-off part of the citizenry. Now let’s consider the social meaning of the income tax. Not the fiscal one, mind you. In the fiscal sense the tax is not that burdensome. Socially speaking, it is a mechanism of redistributing incomes, transferring them from the rich to the poor, from people rolling in money to those in the gutter. The Russians adopted an antisocial approach, the same tax rate for people making millions of dollars a year and those earning, say, three hundred. What about the social role of the tax structure? This is why the EU countries criticize Russia. We can see that the tax structures in Russia and Ukraine do not act as social regulators, which is a key function of taxation.

The Day: Won’t such regulation and leveling frighten rather than encourage our rich, considering that we want them to bring their money out of the shadows?

Azarov: Our rich men are not all that timid, take my word for it. I deal with them on a daily basis, and I know their mentality. Actually, they aren’t afraid of anything and know they can get away with practically anything. Regrettably, we can bring them to account very seldom, hard as we try to influence them using the government machinery. Will they continue to hide their money? Compare the way a Ukrainian businessman operates in this country and elsewhere in Europe. Elsewhere he knows he must pay every tax and the last thing he wants is getting the European equivalent of the IRS interested in him, for this will certainly result in arrest, deportation, and so on. So he has to pay 65%? No problem! In other words, the mentality of a domestic businessman complaining that he is strangling taxes in Ukraine undergoes a remarkable transformation in the West. I recently met with the British ambassador, we discussed British legal assistance in cases of capital flight and money laundering. We spoke of the British Virgin Islands and the Isle of Man, this oasis favored by our businesspeople. I asked the British government to help us legally and by providing information. In principle, this was done in the context of the money-laundering clause of the UN resolution to combat international terrorism. The ambassador told me about the steps being taken by EU countries, and I think that our entrepreneurs will have a hard time taking their money out of Ukraine illegally. There are still many such oases across the world, but there is also the international community’s firm determination to put an end to money laundering. Dirty money is that which has avoided taxes, so a transition to lower tax rates (I can assure you that after the tax reform Ukraine will rank among the European countries with the lowest tax rates), combined with rigid international sanctions, will develop a situation in which businesspeople will see no reason in keeping their money in the shadows. Incidentally, some of them have long realized as much and have declared their incomes worth tens of millions. They say here is our money, and we’ve paid all taxes. True, they mostly declare large sums received as dividends. As you know, our law exempts this money from taxation, so they can declare such sums and never worry. We’ve tried to explain to the Verkhovna Rada that it’s not normal for a businessman declaring dividends worth millions to have wage arrears. Yet all our attempts have not been supported.

AZAROVS COME AND GO, BUT THE SYSTEM MUST KEEP RUNNING

The Day: There is a widespread stereotype. The shadow economy in the transition period — or in a state of chaos — has allowed many people to keep afloat. What are the shadow statistics?

Azarov: We all know that there has been no systematic, deep analysis of the shadow economy. A lot of different statistics are cited. Our department specializes in economic analysis, so we mostly use the ratio of the official money turnover in Ukraine and all those money flows outside the banks, foreign currencies handled by currency exchange booths, and so on. The most tentative estimates point to about 40% of our small- scale commodity production and service sector being in the shadows. 40% of the population’s incomes is that untaxed money, incomes received by our people through unregistered labor.

The Day: Do you see any positive aspects to the shadow economy?

Azarov: The retail network is perhaps the only one, for it allows millions of Ukrainians to earn a living. Small businesses. Quite honestly, we take a rather liberal approach to all this. We can see that the main budget revenues are lost not there, flowing out through different streams and rivers. Small and medium businesses need support. Perhaps two or three out of ten street vendors will with time start medium businesses. Three or four years later some of these might turn into a big business, so the tax people treat them kindly. You may have noticed that we stopped receiving complaints from small cafes, stores, and suchlike. After switching to a uniform tax, the patent, we actually left that sector and concentrated on heavy taxpayers, setting up offices in big businesses, looking for budget incomes where most significant assets are created.

WE STARTED ON SLOVYANSKY BANK LATE IN 1996

The Day: Many disagree with your stand in the case with the Slovyansky Bank — and the case is still open. Why couldn’t you finish investigating the fuel and energy complex and could you briefly tell us the story of this bank?

Azarov: The energy sector conflict started last October, primarily because the money being transferred to the account included the value added tax that had to be paid. I asked the government if it was public money. Was this money to go to the state budget or the electrical power industry could use it as it saw fit? Of course, there are always top priority problems like thermal power plant repair, coal procurements, payments for gas, and so on. Then why not say that the power industry is exempt from the VAT? By the way, the tax on gas, electricity, and coal was instituted on January 1, 2000. There were no taxes before. And so we had the tax but no tax payments to the state budget. The government is the principal manager of budget funds, so it can collect this money and use it at its own discretion. But the government must show exactly how much it has collected and make all the required payments. The previous cabinet took a different position. They reported modifications in the electricity payment collection system. Every month the progress report looked better: 60%, 65%, and now 70%.

The Day: Was it because they made the life of oligarchs difficult?

Azarov: It had nothing whatever to do with the struggle against the oligarchs. That much was clear. As for the Slovyansky Bank, it all began in late 1996 and early 1997, precisely when Pavlo Lazarenko was premier and the Unified Energy Systems of Ukraine was Ukraine’s largest company. According to its director general at the time, UESU turnover came to $10 billion. Naturally, the tax service could not leave the company alone. Before long we found out that most company settlements were handled by the Slovyansky Bank: payments for natural gas, products, and so on. Of course, we wanted a closer look at the bank, considering the staggering sums flowing through it. Moreover, it handled credit transactions with Ukraine’s largest metallurgical combines and the largest foreign exchange operations. Could we ignore such a bank? Very soon we realized that all this was just another link of the same chain, and we became interested in the First Trading Bank of Nauru, a sophisticated financial institution in a remote country, a place you can hardly spot on the map (this Pacific powerhouse boasts a land area of 8.2 miles and at last count 10,390 people — Ed.). Yet this was our bank’s financial agent. Tracing foreign trade contacts took a very long time, but finally we had enough evidence to go to the public prosecutor and start criminal proceedings. I am not going to predict the outcome of the investigation, because anything I say here could be used by someone somewhere. All I can say is that the first hearing is scheduled for mid-December, and that the court will be open, with the media covering testimony made by witnesses and respondents, along with what evidence will be presented in court.

The Day: What about international cooperation against money laundering? Why is receiving the relevant information so difficult?

Azarov: We have to work in a situation such that the political system is just getting on its feet, when the parliament is debating whether we need an authority to combat money laundering, it is very easy to find ourselves listed among countries still wet behind the ears. Especially when the decision makers do not study the situation in sufficient depth. I met with a FATF official, Mr. Greenberg of the US Justice Department. He spent about half an hour lecturing me on what dirty money is all about, the importance of the problem, that no one is doing anything about it in Ukraine, and so on. I was all patience and listened him out, which wasn’t easy. Then I told him about the criminal cases we were investigating, showed him copies of our inquiries addressed to competent authorities in many countries, some still unanswered. Then I asked, “How can we combat money laundering without any assistance from precisely those structures that are supposed to help us?” We can be criticized and accused of acting wrong, but we deserve some assistance, don’t we? If the international data exchange system worked, and we didn’t use it but concealed information, anyone would have been right saying there are no responsible government employees in Ukraine; even worse, that there are bureaucrats harboring money launderers. Mr. Greenberg could not provide a single fact to the contrary. I just don’t understand how can anyone criticize, let alone accuse us. Mr. Greenberg and I agreed that we would closely cooperate and exchange information. Anyway, he promised he’d help. After that some headway was made, and this also explains the degree of progress in the Slovyansky case, and not only there. I’ve mentioned that we did some digging and now we have begun to get documentary evidence. But there are objective complications. Talking to my foreign colleagues, FATF people, I said that the data exchange mechanism wasn’t functioning quite adequately. We are in the twenty- first century and have to exchange hard copies. That’s abnormal. We have enough protected electronic channels to receive classified information, so let’s do it quickly and efficiently. We send an inquiry, you browse your database and send us the required data, so the whole thing takes a couple of weeks rather than a year. That’s our problem, and I hope we’ll be able to do something about it to speed up our investigations.

PRIVATIZATION SO FAR HASN’T SOLVED A SINGLE STRATEGIC PROBLEM

The Day: The Tax Administration has a powerful database. In interviews with The Day, people representing different structures, among them the chairman of the Antimonopoly Committee and heads of the Accounting Chamber and State Property Fund admitted that a number of large enterprises are being privatized using the debt scheme (a.k.a. shadow privatization: run up enterprise debts, have the courts declare it bankrupt, and sell it for pennies —Ed.). They also said that their structures had no information or levers to influence the process. Do you tax people have such information? Perhaps you could name some names? Those interviewed insisted they didn’t even know who has bought Rosava, for example.

Azarov: In terms of tax payments, we are not particularly interested to know who owns a given business under the law. The kind of information you just mentioned should be with the State Securities and Stock Market Commission. That’s the state body responsible for keeping all title transfers legitimate. Such bodies are very important in the civilized countries; they can even conduct criminal investigations. The US Securities and Exchange Commission is a most powerful government agency, handling a vast amount of transactions and title transfers. Unfortunately, we have no information about who owns what business. Deals are often made in such a way that Ukraine doesn’t have the slightest idea about its property changing hands, giant enterprises included. This is a huge gap in our political system. The new owner can be an offshore company listed in a register kept by an obscure bank located God knows where. So practically no one knows about the title transfer. That was precisely how numerous Ukrainian enterprises changed owners. We learn about such changes because we keep track of their tax returns. For this reason the gentlemen in charge of the central authorities you have mentioned, especially the State Property Fund, ought to pay very serious attention to privatization issues, above all the observance of the privatization conditions. As a rule, here lie the roots of all further problems with enterprises, when investment or privatization commitments are ignored in the very first month. No one pays attention, no one sounds the alarm, and no one invalidates the contract.

The Day: Does the president’s directive concerning the Mykolayiv Alumina Plant have anything to do with this situation?

Azarov: Mykolayiv Alumina substantially reduced its output, and the management attributes this to objective circumstances: lower alumina prices. We took an interest in the situation because its payments to the budget showed a sharp decline. This was something to be expected. We have serious doubts about the future prospects of the largest investment project of recent years and are watching the situation very closely.

“I WOULDN’T OVERESTIMATE THE ADMINISTRATIVE RESOURCE”

The Day: You don’t have to be a prophet to predict mounting criticism now that you’re heading a political party. And the limits of propriety could shift any way. How are you going to cope with the dilemma? How would the Party of the Regions respond to the Minister of Internal Affairs or Director of the SBU heading a political party?

Azarov: I wouldn’t overestimate the administrative resource. The more so that no one is going to let our elections pass unnoticed. All the serious international organizations will closely follow their fairness and transparency. It is true that I never instructed any tax people to join our party. Some of the colleagues asked if they could be members of the Party of the Regions. I said better not, not as long as I’m in charge of the Tax Administration and chairman of the party. Suppose the situation changes and I’m replaced by a Social Democrat or someone from the Peasant Party, someone not as tolerant as I am who’ll tell the entire team to join his party. What next? I might take the floor at the party convention and say I want out as chairman, so I can spare the Party of the Regions all that criticism directed at me. But I would want to do so not under pressure but of my own political will. And I’ll do just that quite soon, as the party convention is scheduled for December 14. I will make my final decision. Anyway, I’m not afraid of verbal attacks or compromising materials, not after what I’ve had to endure during the past six months. The president is perhaps the only target of a greater onslaught of compromising materials. Well, that’s something every politician has to face.

DONETSK ISSUES ARE DECIDED IN KYIV

The Day: Early in our discussion you were quite critical about UESU. At one time this company tried to act as a private state planning commission, first for Dnipropetrovsk oblast and later all Ukraine. Today, the status is claimed by the Industrial Association of the Donbas — and not only in the region. How do you feel about this structure?

Azarov: First, there is basic distinction between UESU and IAD. The former used the state resource, actually wielding power using gas, it being public property, and so on. IAD does not use this resource. It is a typical business entity, perhaps best described as a powerful syndicate, but it isn’t the only one, not even in Donetsk oblast. There are other big businesses boasting turnovers matching the IAD’s; they can compete with it. And there are corporations surpassing the association. I wouldn’t want to idealize the IAD, but we at least try to keep it operational within the limits of the law. Actually, I don’t care what business operates where, in Donetsk or elsewhere, because they are all subject to very close monitoring, so anyone assuming that we have left the IAD alone is very wrong.

The Day: Mr. Azarov, how do you like this formula: “Issues relating to Donetsk are not decided in Kyiv?” It is often heard at journalists’ and business people’s get-togethers.

Azarov: I’ve never heard it. It’s untrue. First of all, and you can take my word for it, all serious issues, including those relating to Donetsk, have been and will continue to be decided in Kyiv. The Party of the Regions emerged as a political force precisely because a lot of issues could not be settled at the local level. Incidentally, the interest group that decided to set up our party really gathered in Donetsk and included people from Kharkiv, Zaporizhzhia, Luhansk, and other oblasts — practically all southeastern Ukraine. Has the situation essentially changed in the eight or ten months since then? I’m sorry to say that it hasn’t. If I could I’d say all right, people, that’s your headache, you have all the resources to solve your problems, so go solve them and answer for your solutions. Instead, you come to Kyiv and expect someone to solve them for you. Actually, I think that no one should require from the president, cabinet, even less so parliament solutions to regional or local problems, which can and must be solved there and then. I think I told you or other journalists that about twenty years ago I visited France and met with the mayor of a small town not far from Paris. He showed me the town and pointed as we walked, “Look, I decided to build a school here and a gym over there...” I said nothing, of course, but thought how about the state planning committee, sending your proposals to Paris, getting them okayed, and getting budget allocations? A joke, of course, but it was true that I had to go to Moscow and visit the Gosplan, Gossnab, Council of Ministers, and all kinds of ministries to argue my case and prove my point whenever I wanted to solve a local problem that could be easily solved on the spot. In other words, even twenty years ago it was perfectly clear to me and I am absolutely convinced now. The very name, Party of the Regions, (I’m co-author) speaks for itself. We rely primarily on the ideas of local and regional self-government, comprehensive and balanced development of the territories, and so on. People must live equally well in Kyiv and, say, Horokhiv in Volyn oblast (it’s a village and Kateryna Vashchuk, my fellow deputy in the previous parliament, never tired of telling me about it). That’s not pie-in-the-sky but our direction of development.

“WE AREN’T PRESSURING YOU TOO MUCH, SO YOU CAN BECOME TRULY INDEPENDENT MEDIA”

The Day: We realize that the State Tax Administration cannot support tax preferences, because it has to think of ways to increase budget revenues. What is your personal attitude toward tax preferences with regard to the Ukrainian print media?

Azarov: We are against tax privileges primarily because they obstruct the development of equal competition. However, our own and world experience shows that no one has ever been able to do without tax breaks. Who should get them? Those operating in the priority development or socially important domains. We are for tax privileges granted, for example, to organizations employing the handicapped and so on. Of course, we must support domestic publishers; we are interested in independent Ukrainian media, books in Ukrainian, and so on. In other words, we must either give them tax concessions or accumulate such tax money in special budget accounts and channel it into this sector. Which is the best way is for our lawmakers to decide. The same is true of housing for servicemen. These are transparent and understandable mechanisms. But there are also cases when a private business appears to be cooperating with SBU, the Internal Affairs Ministry, or something. In the end, the money escapes the budget, supposedly spent on housing projects for servicemen... You may have noticed that we are having fewer problems with the media after the tax service addressed rather strong criticism your way. This doesn’t mean that all the media became law-abiding overnight and so on. It’s just the result of, say, a certain change in our outlook. We say we really want to support you; we don’t pressure you too hard; you can have a break and use it to become truly independent media outlets. Yes, I understand it’s very hard. Believe me, I know your newspaper’s economy as well as you do.

The Day: We might as well point out that we have had more than forty inspections in the past three years. But now you are convinced that we are a model taxpayer, aren’t you?

Azarov: I might also add that we submitted a number of proposals for the tax code and other statutory acts. Moreover, I initiated getting back to the presidential edict supporting domestic book publishing. We studied it in order to use it to improve the situation. We discovered that the government, addressed first of all by the edict, for the most part remained inactive. I’d like to draw your attention to this. I think that we should have more Ukrainian translations of Russian and world authors. We must publish them. Whenever I visit Petrivka [Kyiv’s famous flea market with a fantastic assortment of books, video and audio cassettes, CDs, etc.] — and I often do — I see that the most popular books are in Russian. There are practically no quality Ukrainian translations. The more we have them, the more people will read them, of course. I, for one, read a lot in Ukrainian. Recently, I bought a very good collection of modern detective stories. I only wish I could have bought it in Ukrainian! So let us put our heads together and see what we can do about the situation.

Автор Выпуск газеты №: Section