The Ukrayina Movie Theater first showed Jean-Jacques Annaud’s war epic Enemy at the Gate

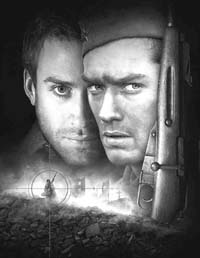

Enemy at the Gate is a film that poses no problems for the audience. This is in fact the end to which it was made. War, love, death, the breathtaking daily routine of snipers, German evil demon Major K Ъ nig, Soviet avenging angel Vasyl, lavish scenery, special effects, and so on leave only one question unanswered afterwards: how many Oscars will this multinational and explosive spectacle win?

The question about Oscars is no accident, for this prize like no other presents a unique global social challenge and points to subjects in demand. Enemy is quite in its element here. For the subject of World War II, shaped in a never-withering genre of a battle blockbuster, has held for some reason a tight grip on US cinema for the past few years. Suffice it to recall the US Motion Picture Academy laurels shared a couple of years ago by Saving Private Ryan and The Thin Red Line depicting the gallantry and sufferings of American GIs in quite different parts of the world. Enemy at the Gate is a sort of counterweight in this line. For, according to Hollywood’s war epics Hitler was bashed and finally defeated exclusively by the formidable Americans with the modest aid of Englishmen. There was not a single word or scene about who made mincemeat of the German divisions on the Volga and near Kursk, who was the first to make the Nazis retreat, and who, after all, stormed Berlin. Enemy at the Gate is a more or less notable attempt to fill this sorely felt gap.

In essence, at first there are even visual parallels with Saving Private Ryan. A classic scene of a front-bound train’s departure, borrowed from Soviet films, is immediately followed by one showing the crossing of a water obstacle and seizing of a beachhead. It is ironic that the Volga should have been reconstructed in Germany, south of Brandenburg. Machine-gun bursts, bodies torn apart, and the battlefield panorama are shown in breathtaking Spielberg style. But actually the plot is based on an idea more rewarding than that of Private Ryan. A duel is a duel. A confrontation of the two giants of sniping is a far more attractive tale than one about a questionable expedition to old Europe in search of an unknown infantryman.

All goes well until the numerous and powerful army of details, the eternal scourge of American films about other countries and remote times, comes into play. What is pleasing is that

Enemy at the Gate does not have many obvious mistakes. Even the Russian inscriptions that catch your eye have been done without mistakes, an unheard-of rarity. But very soon, the historical verisimilitude begins to hit the reefs. It is still a trifle when The Evening Toll, being sung in a battle trench, quickly turns into Steppe All Around. But “Nikita Khrushchev,” a muscular and quite presentable gentlemen, more looks like a hefty US Army colonel than a Communist Party Central Committee Secretary. A simple-minded Urals native, shepherd Vasia Zaitsev (Jude Low), who seems to be making mistakes in writing, thoughtfully pronounces a phrase about the cursed Konig, “He has amazing intuition.” Major K Ъ nig himself sometimes has nothing to do but roam through the ruins of Stalingrad, apparently mined and crawling with other snipers, with the sole aim to vilely kill the Soviet boy. The front-line love affair of Zaitsev and Tania (Rachel Weisz) is rather shown in the glossy-erotic style of Basic Instinct: lice seemed to have no place in the love scene. Then there is political commissar Danilov (Joseph Fiennes) who, disappointed with Communist ideals, heroically commits suicide. And, finally comes showdown as an apotheosis of the fight against unyielding history. The final encounter between the Soviet and German snipers is presented like in the purest Western with capes flying, squinting eyes, and pointblank shots.

On the other hand, Enemy at the Gate could incur the wrath of quite a few in Russia and former Soviet Union in general not only because of gaffes like these but also, paradoxical as it is, because of the historical truth which director Jean-Jacques Annaud also reproduced by some details of a different kind: security units shooting those attempting to run away, one rifle and five rounds for two men so that when one is killed the other picks up his weapon, fear of death without any heartfelt cries of “For the Fatherland, for Stalin,” the half-hearted attitude of commanders to the plight of their soldiers, the many unknown Zaitsevs, Ivanovs, and Petrovs who died for nothing, just obeying inhuman and stupid orders. This is a different war that also raged in Stalingrad, one which no Russian filmmaker has ever shown or will ever show no matter how much the past might be reconsidered.

This is why you feel a lasting sensation that this two-hour film was conceived to save Private Zaitsev as not a hero but an ordinary human being and give him not only a rifle but also a luck which millions of his brothers in arms lacked.

THE DAY’S REFERENCE

Vasily Grigoryevich Zaitsev was born March 23, 1915, in Cheliabinsk oblast, Russia. The grandson of a professional hunter, he participated in building the Magnitogorsk Steel Combine, saw service in the Pacific Fleet, then studied to be a public accountant. Sergeant-Major Zaitsev arrived at the front in September 1942. A hero of the Battle of Stalingrad, he killed 242 enemy soldiers in three months, including eleven snipers sent to hunt him down. He shot down the famed Major K Ъ nig directly in the right temple after an hours-long duel on the Mamai Mound in 1943. Granted the title of honorary citizen of Stalingrad, he was put for life on the list of the military unit in which he served in the war. Afterward he lived in Kyiv, graduated from the Institute of Light Industry, was manager of a farming machinery spare parts plant, the Ukrayina clothing factory, and a light industry college. He wrote two manuals for snipers.

Zaitsev died December 15, 1991, and was buried in Kyiv’s Lukyanivske Military Cemetery.

INCIDENTALLY

Seven years before Jean-Jacques Annaud began work on Enemy at the Gate, the story of famous Soviet sniper Vasily Zaitsev caught the imagination of Yuri Ozerov, the author of monumental war epics Liberation, The Battle of Moscow, and Stalingrad. The latter film, released in 1989, received a chilly welcome from the cinema beau monde then overwhelmed by the euphoria of perestroika. Four years later the director made an original attempt of compilation: having borrowed the Stalingrad scenes from his own movies, he shot a few additional scenes and imbedded them in a new war epic. The film Angels of Death features two snipers, Siberian boy Ivan (Fedor Bondarchuk) and a German ace Johann (Regimantas Adomaitis), who engage in a life-and-death confrontation. A love line is developed alongside. The German is clearly down on his luck: when on leave he finds his wife has been cheating on him. Conversely, Ivan meets and falls in love with a good girl (Yekaterina Strizhenova). However, in the final scene the German major shoots the girl dead but spares Ivan: while the latter is carrying his beloved’s body out; he keeps his sights on Ivan but never pulls the trigger.