WHAT CAUSED THE DECLINE AND FALL OF RUS’?

(Concluded from The Day, No. 8 of March 6)

The principle of dynastic succession at last was established and acquired the status of an unwritten law, marking the beginning of the period of appanage principalities. The tribe, viche, and public opinion as the principal levers of democracy, were now a major obstacle to princely rule.

To the common folk, the very name of the prince was divine, subject to unquestioning respect, because prince meant protector. At the same time, Prince Volodymyr, still regarded as the protector of Kyiv Rus’, made use of both elements of the previous system and principles never before known in Rus’. The principles of Christianity were of a dual nature, symbols of human outlooks and Christian dictates — canons and dogmas.

Evidence of how the father of Christianity in Rus’ treated what was happening in his realm is found in events accompanying the baptism of Kyiv and Novgorod, especially in light of the Commandment, “ Thou shalt not kill.” Novgorod was exposed to terrible ruin and violence, as the people was ruthlessly beaten by Dobrynia and Putiatia acting on Prince Volodymyr’s orders. Meanwhile, the adoption of Christianity was an impetus to the development of architecture, the pictorial arts, and book publishing, with Rus’ being recognized by other countries. And this far from exhausts the list of the results of his step.

What happened in Rus’ under Prince Volodymyr? His elder son Vysheslav was enthroned in Novgorod; Iziaslav in Polotsk (since his mother Rohnida came from the Kryvych dynasty, he was accepted there as a tribal, allodial prince); Sviatopolk in Turiv; Yaroslav in Rostov; Mstyslav in faraway Tmutarakan; Sviatoslav in Smolensk, and Sudyslav in Pskov.

Novgorod was considered the second most prestigious principality after Kyiv. Following Vysheslav’s death Volodymyr had to appoint Sviatopolk in his place by order of seniority, but Sviatopolk was in his father’s disfavor because of his violent character. Instead, Yaroslav was made the ruler of Novgorod and his Rostov seat went to Borys; Murom went to Hlib. In fact, Prince Volodymyr distinguished the two younger sons from the rest and bestowed them with special affection. They were borne by his latest wife, daughter of the Byzantine emperor. There was, of course, the rule of filial seniority as a firmly established tradition, but there was no law on succession. Until the end of Volodymyr’s rule Sviatopolk stayed in Kyiv, closely watched by his father. Later tragic events explain his policy, for Sviatopolk, subsequently known as the Accursed, killed his subsequently canonised brothers, Borys and Hlib.

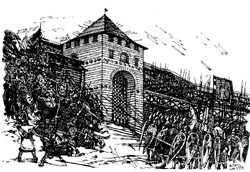

For many centuries no one in Holy Rus’ had encroached on the tribal principles held sacred among the Eastern Slavs. Volodymyr did. Feudal dismemberment of the principalities, struggle for appanages, and rivers of blood were shed by druzhyna corps fighting to protect the interests of allodial princes, at times talented military leaders and brilliant politicians. It was a horrible price to pay by the Slavs and it all ended in the Tatar onslaught and devastation of Kyiv Rus’ in 1237-41.

COULD YAROSLAV THE WISE HAVE PREVENTED THE FALL OF RUS’?

No one knows. Prince Yaroslav had to spend much time on internecine warfare (1015-36). Even the duumvirate with Prince Mstyslav of Chernihiv, Yaroslav’s brother (1026), a very good political move, did not solve the problem entirely. Mstyslav died in 1036, making Yaroslav the Wise the sole ruler of Rus’. Obviously, he must have considered preserving the state’s integrity as his main task.

Suppose we analyze the ways and means he used to do so. In the foreign policy domain, Yaroslav followed in his father’s footsteps, relying more on diplomacy than warfare. He succeeded in getting Rus’ recognized and respected in the international arena. In the Middle Ages, the status of any country was determined by dynastic ties. The more powerful a state was, the greeter the prestige of its ruler and the greater the number of other rulers wishing to establish family ties with him. Almost every Western king considered such ties with Yaroslav the Wise a matter of honor. Prince Yaroslav married Ingigerth (Iryna), daughter of Norwegian King Olaf. Norwegian Prince Harald HМrdrМde (later King of Norway) married Yaroslav’s daughter Elizabeth. French king Henry I married his daughter Anna who, after her husband’s death, became regent to her underage son Philip I. One of his sons, Vsevolod, married Irina, the daughter of the Byzantine emperor Constantine IX Monomachus; Vsevolod’s eldest son Volodymyr from that marriage was named Monomakh after his imperial grandfather.

Yaroslav’s domestic political endeavors resulted in an overall growth and strengthening of the economic and cultural ties between different territories, and by the spectacular development of his capital, Kyiv. His constitution, the so-called Yaroslav Statute or the oldest law code, Ruska Pravda, instituted in Novgorod (1016) as a collection of legal norms of public life deserve separate notice. However, Yaroslav the Wise did not enact a law on succession to the throne, just as numerous East Slavic princes remained adamantly covetous of the Kyiv throne. Again arrows whistled, lances were broken, swords clashed, and the land of Kyiv Rus’ was awash in the blood shed by fratricidal wars.

Yaroslav the Wise died in 1054, leaving sons and nephews among his inheritors, dividing the territories between them. Kyiv, Novgorod, and the Turovo-Pinsk territory went to eldest son Iziaslav; Chernihiv and the Siversk territory went to Sviatoslav; Vsevolod ruled in Pereyaslavl and south part of Left Bank; Ihor in Volyn; Rostyslav Volodymyrovych in Halych; and his third cousin Vsevolod Briachyslavych in Polotsk. His eldest son Iziaslav became the sovereign. Three elder brothers Iziaslav, Sviatoslav, and Vsevolod made an alliance to jointly rule the entire land. This triumvirate lasted for about fifteen years. Volodymyr Monomakh made desperate attempts to keep Rus’ united. Tradition was not the only reason for its fall. Fear of losing power made the princes take special care of prolonging dynastic rule.

Jan Dlugosz, a fifteenth century Polish diplomat and historian (also known as Johannes Longinus), wrote, “After the death of Kyi, Shchek, and Khoriv, their sons ruled in Rus’ for many years as direct heirs, until their legacy passed to two brothers, Askold and Dir.” In his Historiae Polonicae, Dlugosz unequivocally points to dynastic succession as the cause of Rus’ death. Does it mean that none of the princes over the centuries realized or wanted to realize the outcome of this policy? Can one accuse Princess Olha, her son Sviatoslav, Volodymyr the Great, or Yaroslav the Wise of shortsightedness? Perhaps half-and-half. The reason was not only the desire to retain power or political egotism, but also the mentality of the people for centuries rooted in worshipping idols, shamans, princes, and viche-elected elders. And then came the epoch of the absolute supremacy of force. Princely minds remained closed to His commandments about love for thy neighbor and brother raised sword on brother. An eloquent example of princely despotism is found in the poliuddia tribute levied on the populace and forcefully collected by the prince and his druzhyna. Now it was a heavy tax meant to sustain the troops and the severest form of enslavement, as people were made to part with most of what they had or produced.

Human egotism, caring for only oneself, scorn of the laws of society elaborated over centuries, a sharp turn in cultural and religious views, and the people’s naive, unquestioning belief in the rulers were what finally toppled Kyiv Rus’.