Rebellious Anitrevolutionary

This "professional" similarity is mysteriously complemented by their similarity of character, rigorous, even dogmatic, and proselytizing temperaments. They were alike not so much in terms of mentality as Weltanschauung.

Leo Tolstoy at the end of last century argued heatedly with contemporary civilization. Starting with his epic novel which nowadays seems primarily a vicious thrust at the French Revolution and its Napoleonic heritage, he rather quickly moved from the purely literary guild to moralistic, preachy publicist works.

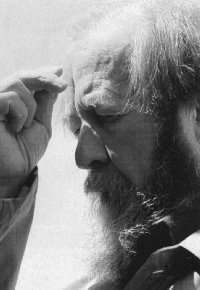

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, born at a time of Eurasian communism, is regarded primarily as that doctrine's most dedicated political accuser. Yet his criticism of communism is only part of that directed against the whole of latter-day European history. He has actually enhanced the anti-Western stand taken by his predecessor, raising it to the extreme.

Christian extremists Tolstoy and Solzhenitsyn radically revised everything attained by the West, from the Renaissance to current developments, and were utterly dissatisfied by what they discovered, be it individualism or socialist projects with their godlessness and mass ideological hallucinations; from various forms of creative culture to technological obsession. Everything was wrong. In fact, the parallels between Tolstoy and Solzhenitsyn are many, so much so they are likely to give rise to countless doctorate theses.

Count Leo Tolstoy, despite his aristocratic descent (and partly because of it) emerges in his outbursts of critique as an ideological inheritor of Russia's age-old rebellion against world realities, history, culture, even nature (e.g., his belated rejection of marriage, eroticism, etc.).

This rebellion dates from Muscovy and stays with Russia, manifesting itself in our current Time of Troubles. The revolutionary is one of the age-old protagonists of the Russian drama. He can come out against God, like Bakunin and Lenin; in defense of God, like Archpriest Avvakum and other Old Believers; against the West, like Slavophiles and Bolsheviks; in defense of the West, like the Westernizers and like-minded people such as Sakharov and Starovoitova. Be it as it may, this revolutionary is first of all a rebel. He denies all set forms and institutions which he stumbles on and follows his own obscure paths, as did both Tolstoy and Solzhenitsyn.

The former referred to common sense borrowed from Jean Jacques Rousseau while the latter hates Rousseau. However, both show an elation in destruction, in laying waste to all they consider unreal, unjust, or unfair. Perhaps this is criticism directed against that which does not exist from the standpoint of that which can never be. However, criticism becomes a reality, wrathful, uncompromising, and fanatically sectarian.

Characteristically, while totally rejecting Russian communism, Solzhenitsyn puts forth its alternative - Russia at the start of the twentieth century. In other words, "the Russia we lost," to quote from a Ukrainian filmmaker, the Russia which Tolstoy battered with such ruthless dedication (and he must have known that Russia much better than all of today's filmmakers put together, and better even than Solzhenitsyn who has dug through mountains of literature about that Russia but finally saw in it only that which he wanted to see).

Indeed, the point is not doctrines or concepts, but a mentality refusing to accept the surrounding imperfect world and perpetually challenging it.

All those "permanent revolutions" are child's play compared to the depth of such rejection. Leon Trotsky believed prior to World War I that the world crisis was primarily manifest in the "cadre," all those at the helm of the "worldwide revolution." Solzhenitsyn's "revolution of the spirit" knows no cadre problems; it proclaims that the world knows no figures capable of carrying out this revolution.

Except the propagator, of course. The propagator points to Stolypin's Russia as his historical ideal. However, The Gulag Archipelago, among other things, tells about fugitives from a Stalin death camp who reached Afghanistan, whence they were returned to the USSR "by the Afghan government, as base as any other government." It would be interesting to hear how such an a champion of absolutist autocracy as Pёtr Stolypin would respond to such an attitude.

Solzhenitsyn was considered a champion of human rights, but then he spoke his mind on Anglo-Saxon civilization, particularly on Great Britain: "Everything has been rotting away there, since Dickens's time." One is grateful for his leaving Dickens himself alone.

Advocating a strong state, Solzhenitsyn simultaneously demands from it a regional autonomy akin to Prince Kropotkin's anarchism. Although the writer proclaims his hatred for Kropotkin's "black flags from out of nowhere," yet his maximalism often comes close precisely to the early twentieth century anarcho-syndicalist when Cuban streetcar drivers wrote to their patriarch at Yasnaya Polyana: "Dear Comrade Tolstoy, we are pleased to report that our strike ended successfully..." Coal miners could have written something like that to Solzhenitsyn from the Kuznetsk coal basin or from Vorkuta, except that they would never mention a successful end.

Rebellion against liberal democracy currently takes place under the guise of conservatism. But once conservatives and reactionaries dare announce that Solzhenitsyn shares their ideas he will "excommunicate" them from his sect, even anathematize them (suffice it to recall his attitude to the last of the Romanovs and all monarchist projects). The Communists in Russia may have counted on Solzhenitsyn as an ally at first, but got only Govorukhin, a person worthy of only a brief screen biography bereft of talent and a petty political careerist.

Hardly any of our contemporaries could withstand Solzhenitsyn's tempestuous all-embracing rebellion whose genealogy reaches back through the mist of national and world epochs when people tended to come out with rash, totally unreal alternatives to the reality surrounding them. The Russian revolution emerged as a local manifestation of that trend, no more and no less.

Yet, there is one thing about this rebellion that is precious in our bloodstained century, something that obviously links Solzhenitsyn to Tolstoy: human life can by no means be thrown on the altar of some rebellious goals or another. Man can only be regarded as an end, not as a means.

Now this is a revolution as such against revolution that never bothered to think of the value of human life. Count Leo Tolstoy argued with Russian revolutionaries as heatedly as he did with the Romanovs. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in his attacks on modern civilization has gone and still goes to extremes and paradoxes that simply do not fit in with the pattern of our modern mentality, shell-shocked by history as it is. However, the revolutionary's final argument, violence, is carried beyond the margins of history. In the heat of the Chechnya War this "imperialist-imperiophile" said that if the Chechens wanted out, well, let them. Get fifty cottages ready for foreign embassies in Grozny, but then leave Russia bloody well alone, too.

Ukrainian patriots, especially those recently surfaced on the wave-crest of history, form a rich assortment of literary Ukrainophobia. Should one protect Solzhenitsyn from them? Should one remind that this "Ukrainophobe" was the first to portray a touching image of a Ukrainian peasant serving under Bandera's banners in one of his samizdat writings? That he constantly stresses his half-Ukrainian parentage? The trouble is that the writer's constant rebellion reduces to dust, in passing, everything that is a strategic obstacle in the road of Ukrainian self-assertion - and any other self-assertion, for that matter.

In the twilight of his mediocre literary career the Russian poet Benediktov

wrote a "long line": "The world fought the serpent's venomous might ..."

I don't know about the world, but Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn indeed fights

the Beast.

Выпуск газеты №:

№45, (1998)Section

Culture