The Dragon’s people

How and why tyranny grows new heads: Evgeny Shvarts’ viewpoint

Eight – not “just” eight but “as many as” eight – revolutionary months, filled to capacity with tragic events, have passed since the victory of the Maidan and flight of the Yanukovych regime’s criminal “leaders” and servants, including embezzlers from among the MPs and law-enforcers. We have seen the presidential and parliamentary elections which official political scientists call an unequivocal success of the democratic pro-European forces. But, for some reason, there still remains a sensation of acute, almost painful, alarm: the battle for an independent Ukraine is not over – on the contrary, it has only begun! And its outcome will depend to a large extent on whether we will understand who our enemy is. Who are we fighting against?

“Who against?” the reader will ask in surprise. Obviously, against the authoritarian Kremlin regime with Vladimir Putin at the head, his mercenaries, his regular army in the Donbas, and the separatists he has let loose. Yet, it is true. To some extent, though. This writer happened to see again the other day Mark Zakharov’s well-known perestroika-era film To Kill a Dragon (1988) starring Oleg Yankovsky as Chief Monster. I was stunned with a suddenly discovered outer and, what is more, inner similarity between a morbid and glassy stare of the “accursed lizard” played by the now late Yankovsky (word has it that the actor had special makeup applied to him), on the one hand, and Putin’s cold, cruel, closed, and relentlessly malicious glance, on the other. I carefully reread The Dragon, a famous “fairytale in three acts” by Evgeny Shvarts, on the basis of which the film was made. Yours truly has already discussed this terrible fairytale-parable (intended for courageous and wise adults) on the pages of Den, but the political, social, and spiritual cataclysms of 2014 make me turn to this subject again. For it is necessary to reconsider them not only in terms of facts, using the instruments of historians and political scientists, but also in a profoundly philosophical way in order to expose the hidden “intertemporal” essence of what is going on. For tyranny, “draconianism,” violence, and aggression have always had similar features. When you take this into account, you understand that the fairytale-parable Shvarts created in 1943 at the height of World War Two, which was immediately banned and never staged in the theater on an adequate philosophical level, is important and valuable today because it makes it possible to see the enemy’s face clearly, catch his morbid stare and the course of his thoughts (here a parable is better than a political analysis), and, what is more, understand who is confronting us.

Actually, it is not so much Putin the Dragon who is confronting us. He can and must be defeated and destroyed, even though at the cost of superhuman all-out efforts, which Lancelot does in Shvarts’ play. Those who confront us are the Dragon’s people “brought up” by the tyrant on his “values.” It is no accident that the monster says proudly: “My people are very scary. Won’t find any like them anywhere. Solid piece of work. Hewn them myself… My dear man, I crippled them myself. Crippled them exactly as required. You see, the human soul is very resilient. Cut the body in half – and the man croaks. But tear the soul apart – and it only becomes more pliable, that’s all. No, really, you couldn’t pick a finer assortment of souls anywhere. Only in my town.”

Putin also has a good reason to be proud. He – in cahoots with his information-propaganda toadies, TV presenters, political scientists, journalists, and actors – has really “hewn” a Dragon’s nation out of a considerable part of the Russians. These people are quiet, meek, scared, spiteful, suspicious, and haughty, for nobody else has a Dragon like “ours” (Shvarts puts it bluntly: “The only way to get rid of the Dragon is to raise one of our own”), and, at the same time, abysmally stupid (Shvarts: “The most tragic thing is that they all keep smiling”). These people kowtow to their tormentor who “eats up” the best of them and robs his slaves of food (Shvarts: townsman Miller “kissed the Dragon’s tail every time they met,” another “citizen,” Friedrichsen, presented the Dragon with a three-stemmed pipe engraved “Yours Forever,” while Anna Maria Frederica Weber said she was “in love with the Dragon” and carried pieces of his talon in a velvet locket around her neck. And the point is not in German names, which is easy to explain as the fairytale was written in 1943, but in the Dragon’s words to his people: “We learned to understand each other from time immemorial.” This is true). And it is not the most terrible thing that the Dragon annually takes a beautiful girl to his cave, where she dies of disgust. More terrible are the words of the Gardener who knows his trade and seems to be an “honest” man. He had recently shown the Dragon a collection of the splendid multicolored roses he bred. “His Excellency” (the Dragon is also called like this) liked the roses very much, and he promised to give the Gardener money for further experiments. But there is a war and a revolution going on, and Lancelot challenges the Dragon to a fight. Nobody cares about roses, and the Gardener is in despair: should the Dragon die in the duel, this will thwart all his plans. And one of the town officials is also deeply distressed: Mr. Dragon has just begun to look into the municipal self-government (although he has been ruling for 400 years), and now this mishap…

VLADIMIR PUTIN AND THE DRAGON (OLEG YANKOVSKY) IN MARK ZAKHAROV’S FILM. THE REAL “BOSS” IN THE KREMLIN AND SHVARTS’ TERRIBLE LITERARY CHARACTER… AT FIRST GLANCE, WHAT CAN BE IN COMMON BETWEEN THEM? BUT LET US NOT JUMP TO CONCLUSIONS / Photo from the website KINOPOISK.RU

The Dragon is really an “expert in communication with people” (as Putin once characterized himself). In Shvarts’ play, he developed a foolproof “triple recipe” to influence his slaves: firstly, if someone refuses to obey, his relatives and friends will suffer (the Monster says bluntly: “I’ll kill them all!”); secondly, “any hesitation will be punished as disobedience” (!); and, thirdly and very importantly, “Mr. Dragon knows how to reward loyal servants.” This is in fact a triune formula of the strong Draconian power: fear, punishment for the slightest hesitation, and reward for loyalty. The history of both Nazi and Stalinist totalitarianisms is ample proof of this. (Stalin’s predecessors in Russia’s tsarist and imperial history also “distinguished themselves,” and their heirs are now “at their best.”)

The linchpin of Shvarts’ play is research into the nature of the people’s “dead soul” and the problems of historical memory. The Dragon has been keeping hold of the people for 400 years on end (Shvarts’ parable repeatedly stresses this; the reader can view the tyrant as not only a concrete historical personality, but also a generalized image; the Dragon’s power also means an unchangingly slavish way of thinking and acting: “This is a very quiet town. Nothing ever happens here,” and obligatory hatred for the enemy (in Shvarts’ play, Gypsies are the enemy, which is in line with realities in Nazi Germany. The Gypsies are dangerous because “they penetrate everywhere,” but today the Kremlin considers Ukraine, Georgia, the US, and quite a few NATO countries in Europe as enemies, and this list is rather “flexible”), and the subservient readiness to “stand at attention” in front of “their own” ogres on the throne (for “as long as we have a Dragon of our own, no other dragons will dare touch us.” That’s the crux of the matter!).

Honoring the traditions of mythology, Shvarts vests the Dragon with hyperbolized scary features in his anti-totalitarian parable: the monster is three-headed (and each cut-off head grows again easily and fast, almost instantaneously), has four paws, each of them having five knife-sharp claws as big as a deer’s horn, breathes out flames which “make the woods burn,” is totally covered with scales which “you can’t cut with a diamond.” He is “as tall as a church.” The Dragon is strong, and everybody considers him “invincible.” The pro-Kremlin media are instilling similar ideas in the “electorate” of present-day Russia: our president is “omnipotent,” he is the guarantor of “Russia’s might,” etc. But let us note a different thing: as many characters of the play say, the Dragon “has been living among humans for so long that he turns into one himself from time to time, and drops by for a friendly visit.” Besides, the Dragon has three different images, three faces. Very interesting! The first image: “An elderly, gray but sturdy, rather youngish-looking man with a military air about him. He smiles widely. In general his manners, while crude, are not without charm” (a curious portrait). The second image: “a somber, reserved, highbrowed, narrow-faced graying blond man,” and finally the third one: “a tiny, deathly pale, elderly man.” Let us put aside all kinds of the likely similarities and allusions but, instead, note that, in the course of many centuries, the Monster has “formed a strong bond” with his people who see him no longer as a monster but as a human. And this is really terrible.

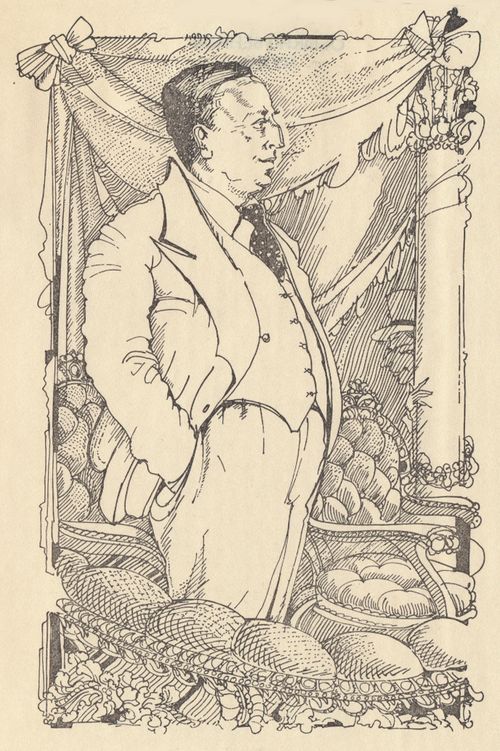

EVGENY SHVARTS (PICTURED). THIS “AUTHOR OF CHILDREN’S FAIRYTALES” PENETRATED IN HIS PARABLES INTO THE ESSENCE OF TOTALITARIANISM AND SLAVISH MENTALITY DEEPER THAN DOZENS OF HISTORIANS AND POLITICAL SCIENTISTS DID / Illustration to Yevgeny Shvarts’ book Selected plays (Chisinau, 1988)

The point is that residents of the “Draconian” city do not play in “manners” and “ideological rituals” (which Shvarts shows very well) – they follow them just because it is the only possible way of life for them. This guarantees the strength of the Reptile’s tyrannical power. But the essence remains unchanged, and after Lancelot slays the Dragon in a duel, he, seriously, almost fatally, wounded, has to leave the city. What happens next? This is interesting and worthy of a special discussion.

The Dragon is called (now that he is dead) “abominable,” “antipathetic,” “inconsiderate,” “disgusting,” “son of a bitch.” Sky-high praises are being sung of the “conqueror of the Dragon” and the “liberator of the town.” But if the reader thinks it is the hero Lancelot, he makes a bad mistake. The townspeople are told that the one who “defeated” the Dragon is the Burgomaster, the slave and sponger of the Reptile when the latter was in power, the Burgomaster who reported daily to the Monster: “Your Excellency, there were no extraordinary incidents within the limits of the town entrusted into my care,” only to hear a curt and extremely clear response from the tyrant: “Get lost!” But now the Burgomaster is the President of a free city, and a high commission (perhaps from parliament) has officially found out that no other than he, the new President, killed the Dragon. The commission established the following: “The deceased braggart Lancelot [in reality, Lancelot was, fortunately, alive. – Author] only infuriated the deceased monster by inflicting a superficial wound. It was then that our former burgomaster, now president of the free city, flung himself onto the dragon and killed him, this time conclusively, while demonstrating assorted feats of courage (Applause). The noxious weed of vile slavery was excised exhaustively from the soil of our collective civic consciousness (Applause).”

The people were thus “liberated.” But, let us recall, they are the Dragon’s people whom the Reptile himself “hewn” in line with his goals. Slaves remain slaves, and we can hear people extol the new ruler (although the service staff explains in detail: “You all know the kind of person the conqueror of the Dagon is. He’s a simple, almost naive, man. He likes sincerity, intimacy”). As for the brand-new President himself, he has excellently learned the “rules” of the disgusting “game” and knows very well how “to address problems.” Here is a fragment from his dialog with Charlemagne, a highly intellectual historian and archivist, the father of beautiful Elsa whom the President wants to be his wife against the will of Charlemagne.

Burgomaster (now President): Elsa’s happy, right?

Charlemagne: No.

Burgomaster: Nonsense. Of course she is. And you?

Charlemagne: I am desperate, Mr. President.

Burgomaster: Such ingratitude! I have defeated the dragon…

Charlemagne: I beg your pardon, Mr. President, but I cannot make myself believe in that.

Burgomaster: Yes you can!

Charlemagne. Honestly, I can not.

Burgomaster: Of course you can. Even I believe it, and so can you.

Charlemagne: No.

Heinrich, Burgomaster’s son: He just doesn’t want to.

Burgomaster: But why?

Heinrich: Trying to jack up the price.

Burgomaster: All right. I am offering you the position of my first deputy.

Charlemagne: I don’t want to.

Burgomaster: Nonsense. You do.

Charlemagne: No.

Burgomaster: Stop bargaining, we don’t have time. Public housing, the apartment is next to the park, near the market, hundred and fifty three bedrooms, all windows look to the south. A fantastic salary. In addition, every time you go to work, you get relocation expenses, and when you go home, you receive a paid leave. Go to a party – we pay you daily allowance; stay home – there’s rent compensation [for the post-Soviet elite, not so much. – Author]. You will be almost as wealthy as I am. Done. You agreed.

Charlemagne: No.

Burgomaster: What is it you want?

Charlemagne: We just want one thing: leave us alone, Mr. President.

Why on earth is the Burgomaster-President so confident in himself (although he frankly confesses to his son when asked “Why are you rubbing your hands, daddy?” “Ah, sonny! Power just fell into them all by itself!”)? And this is what he says himself, answering this question: “Listen, you, my dear! [he says this to Charlemagne after the latter disapproved of his daughter’s marriage to the President. – Author]. You are not getting more. You are obviously after a share in our enterprise, aren’t you? Well, you can’t have it! Everything that the Dragon was brazenly appropriating is now in the best possible hands. That is, mine. And partially Heinrich’s. This is absolutely legitimate. You won’t get a penny of it!” Then goes a retort from Heinrich, which is worth many pages of the text (also addressed to Charlemagne): “What a tiresome mode of bargaining!”

The tragedy of Ukraine is that this is the only way the egoistic, greedy, and complacent Burgomasters, who regained power very quickly after the Revolution of Dignity, can think. The threat to this revolution and the Maidan’s ideas emanates from the same Burgomasters who “address the problems” of politics, the economy, culture, and, what is more, defense (!) in this country by way of “untiring” methods of bargaining – I will give in to you in such and such matters, and what will you give me in return? Those who refer to this “style of management” as “civilized compromises” should understand that it is essentially the Dragon’s style, for even the Monster far from always resorted to the use of force – he often preferred to buy off (suffice it to recall the Gardener).

The crux of the matter is as follows. In Shvarts’ parable, the last, dying, head of the Dragon sighs and hisses: “Let me start this all over! I’m going to squash the lot!” (Incidentally, grinding the claws and smearing them with poison before the fight with Lancelot, the Dragon says: “I won’t say when I will start. A true war begins all of a sudden.” These words are worth paying attention to). The Dragon who really rules the northern superpower is alive and strong, and only the entire Ukrainian nation can be the Lancelot who will defeat him if it reads the following line from Shvarts’ fairytale: “Their souls are straightening out. Why, they are asking, why did we feed and tend that monster?”