The American Kozaks: mission and individuality

Their “empire” embraced various professions, civil and cultural initiatives, but most of all influenced artistic and intellectual life of the Ukrainian community beyond Ukraine

The cultural (and now historical as well) phenomenon of Edward (Eko) Kozak, patriarch of the brilliant artistic Kozak dynasty, restrains in some way from styling his sons Yuri (1933-2001) and Yarema (1942-2016) prominent artists. But in fact, judging by their heritage, that is exactly what they were. Either was conscious of his father’s genius in the realm of graphic art, painting, publishing, creative and intellectual journalism, and first and foremost cartoon, and thus would not disturb the established balance of public opinion of the Kozaks in the history of the 20th-century Ukrainian national culture. Today Ukraine should revere them for what they achieved for their fatherland overseas, in the US, where they consolidated their gifts as artists and revealed them in various branches of art.

Yuri Kozak was born on December 14, 1933 in Stryi near Lviv. His mother Maria (nee Bortnyk) put a lot of effort into bringing up her older son while her husband Edward Kozak’s popularity was growing (he was a graphic artist and editor of Lviv’s most popular satirical magazine Komar (“Mosquito”) and the pupil with no one other than Oleksa Novakivsky self). According to family legend, as a young child Yuri co-authored his legendary father’s cartoons, seated on his father’s shoulders at the writing desk in their modest rented apartment in Piskova Street in Lviv. This undoubtedly shaped the adult Yuri Kozak’s fate.

Yarema Kozak was born on April 17, 1941 in Krakow, Poland, where the Kozaks were forced to move after Lviv was occupied by “the first Soviets.” By that time Eko, who had earned quite a weight in various public, cultural, and artistic circles, had been elected president of the Ukrainian art club Zarevo (“Glow”), which kept functioning in Krakow under the German occupation. Here again, among hardships and threats to family happiness but under the flag of Ukrainian art, yet another Cossack character began to take shape.

In 1949 the Kozaks moved to the US and settled in Detroit, Michigan. This city was to become the seat of the entire American Kozak “empire,” which embraced various professions, civil and cultural initiatives, but most of all influenced artistic and intellectual life of the Ukrainian community beyond Ukraine.

In 1952, after completing high school, Yuri received a scholarship from the Detroit Center for Creative Studies, where he honed his skills in painting, graphic art, and sculpture. After graduation he taught drawing as an intern. In 1957 he married Suzanne Ellis. In the same year he started working at a stained glass studio, executing commissions from various American churches. Later, in other jobs, he also perfected his skills as mosaicist and muralist.

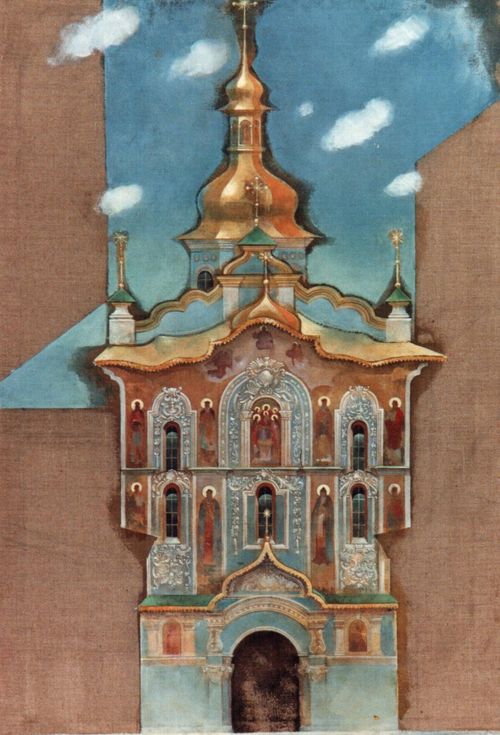

YURI KOZAK. ST. TRINITY CHURCH IN KYIV. 1980s

As a true Kozak and Cossack, as a child Yurko (just like his younger brother Yarema) joined Plast, the Ukrainian scout movement. This patriotic training and spiritual experience had a positive effect on the brothers’ productivity and subject matter of their works. Their father involved them both in illustrating the satirical magazine Lys Mykyta (“The Sly Fox”), as well as children’s magazines and books. Yuri Kozak’s own “portfolio of ideas” was filling as he was turning into an original and often unique graphic artist, painter, and designer.

The Ukrainian artist’s versatility was noticed by General Motors managers, who in 1965 offered him a job as a designer. For over 30 years Kozak contributed to developing new Buicks and led the industrial sculpture (automotive design) department.

YURI KOZAK. THE LEAVES. 1970s

Meanwhile, outside his main job George (Yuri) Kozak was still known as Yuko (this was the artist’s sobriquet, similar to his father’s Eko). In 1959 Edward Kozak involved Yuri into illustrating the children’s magazine Veselka (“Rainbow”), known among the Ukrainian communities of the US and Canada. Since 1961 his drawings became quite bold in what concerns form and style. It is worthwhile mentioning that they appeared in Veselka next to works of such renowned artists as Mykola Butovych, Halyna Mazepa, Petro Andrusiv, Petro Kholodny Jr., Mykhailo Mykhalevych, and of course Eko. Throughout the 1960s and later, in the 1970s and 1980s, Yuri Kozak’s graphic works enriched the artistic and meaningful space of the publication and sometimes even outnumbered his father’s, which enormously pleased Kozak Sr. who was then able to dedicate more time to political satire.

It is noteworthy that in the genre of magazine graphic art Yuko learned from his father to avoid repetitions in his technique and instead modify compositional and formal solutions. That is why his works represent to a certain extent the stages in the development of his creative thinking which was obviously synchronized with his experience as GM automotive designer. Besides, there were other branches of art which proved Yuri Kozak’s extraordinary artistic talent, such as easel and sacral painting. For St. Josaphat Church in Warren, Michigan he made the altar icon and the iconostasis; he completed the decoration of St. Michael’s Ukrainian Catholic Church in Dearborn, Michigan. While sticking to the canonical principles of iconographic types in the Byzantine tradition, he succeeded in enriching the interpretation of sacral sense with individual qualities. He achieved an even more unexpected effect in his series depicting the architecture of famous Ukrainian monumental churches (The Vydubychi Monastery, St. George Church in Lviv, St. Nicholas Church in the village of Kryvka, St. Trinity Church in Kyiv and others). Here he combined artistic and methodological challenges of scientific reconstruction of architectural heritage with documentary graphic art, as well as with the perfectly honed painting technique of a hyper-realistic work, which was a rare occurrence in Ukrainian practice. In the run-up to the Millennium of Christianity in Ukraine, the Canadian Ukrainian Art Foundation from Toronto, Canada commissioned a painting reflecting that pivotal historic event. Today this monumental canvas decorates one of the city’s Ukrainian cultural institutions.

YAREMA KOZAK. A HUTSUL GIRL. 1980s

The heritage of Yuri Kozak (died on January 20, 2001) includes numerous works in other genres of painting, in particular, portraits, historical paintings (Prince Ihor’s Campaign being one of the most famous) and still lifes. He has also executed numerous settings for performances based on American plays and operettas.

Yuri Kozak and his wife had five children. The oldest, Roman, is a priest in the Greek Catholic Church; Stephan is a ceramist and follows in his father’s footsteps as automotive designer, Maria is a stained glass artist, Tetiana is a painter, and the youngest Edward became an automotive engineer.

Moreover, Yuri Kozak was active in maritime branch of the Ukrainian scout organization Plast and was member of the well-known kurin (fraternity) Chornomortsi (The Black Sea Rovers). His younger brother Yarema kept abreast with him. He was as active both as an artist, a public and cultural figure in the US, and a plastun (scout) known in the same fraternity as Sharko. He studied at the arts department of the Wayne State University in Detroit. From 1964 to 1971 he finished college and obtained a PhD. In 1965 he married Khrystyna Baiko with whom he had two children, Ksenia and Irynei.

In 1968-75 Yarema Kozak headed an art school for the youth at the local Cultural Community Club, where he worked with 45 students. At the same time he acquired his individual traits as a graphic artist and painter. His first personal exhibit was held at the library in Hamtramck, Michigan in 1969.

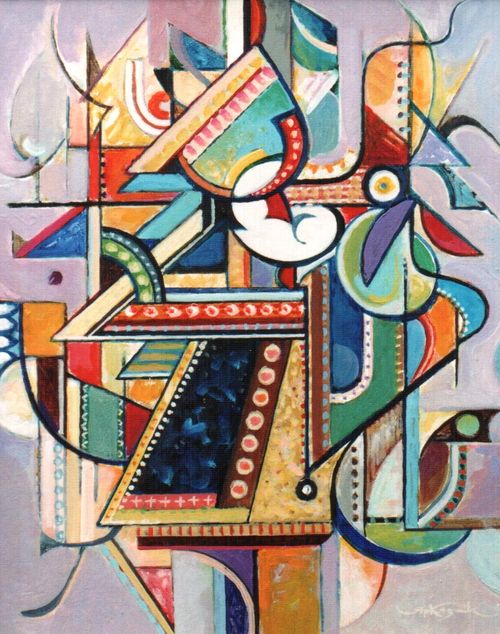

The structure of Yarema’s art somewhat differed from that of his brother’s, in accordance with the context of his training as professional artist at the university, as well as his greater involvement with easel painting. The artist had a finely tuned sense of time, he followed the most recent trends in American and world art and showed interest in abstract art. At the same time, notwithstanding individual paraphrases from Robert Rauschenberg, Jackson Pollock, and other representatives of abstract expressionism, he looked for ways to synthesize modernism with ethnic Ukrainian background (notably, this is exactly what the young Eko did back in Lviv).

The scope of the artist’s expressive means is spectacular: from post-impressionist, post-Sezanne, neo-expressionist remarks to post-structural game of forms. Yarema’s particular emotionality which revealed itself through the choice of saturated, luminous color scheme could be ascribed to the painter’s admiration for his parent’s fatherland (which he physically was never able to see). In his icon-painting the author tried to stick to canonical prototypes, and here his individual style is harder to discern.

The variety of Yarema Kozak’s approaches towards plasticity and form in easel painting still allows to perceive all painting genres (symbolic scenes, landscapes, and abstract images) as an artistic, esthetic whole. However, at the same time he was active in other branches of art, and mostly in graphic art. In 1975, together with his brother Yuri, he illustrated the extensively reprinted publication of the Association of Ukrainians Educators in Canada My First Dictionary, and in 1986, the chrestomathy The Millennium of Rus’-Ukraine, published by the World Congress of Free Ukrainians. In 1989 at a big ethnic art competition (with 300 participants) in Michigan he won the First Prize, and he had received two other decorations before that. Yarema Kozak passed away on January 16, 2016.

Eko, Yuko, and Yako, the famous American Kozak family, were very popular among Ukrainian immigrants. Besides joint exhibits (including one in Lviv in 1990), the Kozaks executed monumental decorative works of art at various sites. One of them is, for instance, a huge map of Ukraine, with motifs from Ukrainian history and national culture at the Wayne University in Detroit. Since then the location is called Ukrainian Room.

Edward Kozak’s daughter Natalia Mordovanets, unlike her brothers, did not follow the artistic path. Nevertheless they, just like Eko’s grandchildren, and later the grandchildren of his children Natalia, Yuri, and Yarema, have always been conscious of their cultural mission to propagate the image of their fatherland in the free world. The versatile heritage of Yuri and Yarema Kozak must at last find recognition in Ukraine and due appreciation in artistic and scholarly circles.

Newspaper output №:

№48, (2017)Section

Close up