The “institution of reputation” as a tool to fight “kleptocracy”

Sergejus MURAVJOVAS:“Previously, Lithuanians believed that no tool could defeat corruption. We do not think so anymore”

On May 31, the National Agency for Prevention of Corruption (NAPC) (a body specially created by the Cabinet of Ministers to check whether officials’ lifestyle corresponds to their declared incomes) made its second attempt to start auditing electronic declarations of the cabinet’s officials.

The first attempt failed, according to the head of the Center for Political Studies and Analysis Viktor Taran, because members of the NAPC and public representatives were given resolution drafts that contained only conclusions (and even those were of questionable quality). Meanwhile, the request for a commission report that would contain analytical information underlying conclusions about the good faith or bad faith of this or that government official was denied.

Civic activists are openly skeptical about the NAPC’s ability to create a more or less clear document that would give a fair assessment of “tons of cash” present in the ministerial declarations, because the Agency has not yet been able to verify top politicians’ declarations for 2015, which they submitted six months ago.

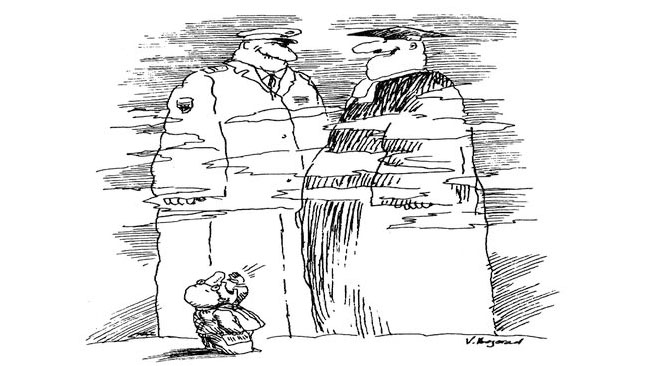

Fabulous riches of top politicians, which are totally out of step with the average citizen’s situation, are a common feature of almost all the countries that were part of the socialist camp once. Kleptocracy is a kind of legacy received from the USSR, and getting rid of it is extremely difficult, but still doable, Lithuanians believe. The Day discussed their success and tools of combating top-level corruption in countries affected by the Soviet machine of political repression with the executive director of Transparency International’s Lithuanian branch Sergejus Muravjovas.

The Transparency International Corruption Perception Index for 2016 saw Lithuania falling down two positions, as it is in the 39th place now. How do you explain this rollback?

“I would not use loaded terms such as ‘rollback’ when it comes to variations amounting to two points. Unfortunately, the result which you mentioned does really show that Lithuania has ‘stalled’ in its fight against corruption. However, let us wait for this year’s result to see if, by chance, it has turned into a trend.

“In Lithuania, we produce many different studies which allow us to assess the progress or regress in the fight against corruption. It is these studies that show that over recent years, we have really managed to break the spine of bribery. Our most important achievement is a change in public attitudes. Previously, Lithuanians believed that no tool could defeat corruption. We do not think so anymore. This is well illustrated by the example of our traffic police. According to the latest data from the global corruption barometer, only 6 percent of people who had contact with the police in Lithuania bribed them. This is four times better than the result we had several years ago. Then, almost one in four Lithuanians admitted that they bribed the police sometimes.”

How have you achieved this result?

“I think it has come primarily because police leadership decided that corruption was a problem to be solved. Secondly, they began to consistently punish those police officers who were caught taking bribes. There were many dismissals and criminal cases. It has made a person who intends to join the police in Lithuania much more aware that bribe-taking does not pay. There are a variety of safeguards that allow us to control the police. For example, a police officer has no right to be in possession of a large sum of money while on duty.

“We do have good results in the police. We need to do the same in the health care industry.”

Photo courtesy of the author

Do doctors take bribes in Lithuania?

“There are such issues.”

And what about civil servants?

“Before we talk about bribe-taking in government, I would like to mention our main problem, which is nepotism. Civil servants promoting their relatives, friends, and acquaintances is a form of corruption, which, according to businesspeople and representatives of civil society, is very common in Lithuania and needs to be addressed. But, of course, it has to be understood that the fight against corruption is not a sprint, but rather a marathon.”

After Lithuania stopped buying Russian gas, has the influence of “the Kremlin money” in Lithuanian politics diminished or not?

“Unfortunately, I am not the best expert on this subject. However, increased activity of anti-corruption bodies sends a signal to businesspeople and politicians alike that they need to start playing by different rules. As a member of the OECD and part of the EU for more than a decade, we must learn to clearly declare our interests and be very careful in dealing with partners.”

However, does Russian corruption still affect your politics today? Or are you not noticing it?

“When commenting on Russian corruption and its impact on Lithuania, I would still like to discuss Lithuanian business activities in Russia. Of course, we in Vilnius cannot be certain that some company of ours which has invested in Moscow or your city of Kyiv will not accept the rules of the local shadow economy. But as far as I know, there have been no recent scandals about Lithuanian companies bribing Russian or Ukrainian government officials. The OECD has very strict rules, according to which we must be very attentive to the behavior of Lithuanian business not only in our country but abroad as well. And I think that our business community is beginning to understand this. How will this affect their activities, is too early to say, but I think they would have to pay more attention to risk management in the markets where corruption indicators are very high.”

We know that Lithuania has a very strong institution of reputation. When a politician has some incriminating information which is supported by indisputable facts appearing in the media, they leave the office. How have you achieved it? Was it the EU that has so affected you?

“We were different five years ago. Today, young people meticulously study the background of the company and its owners before they look for a job with it, and they do not choose a job where there are skeletons in the closet. I think it is only a matter of time before Ukraine becomes like that. The world today is a very competitive place, and reputation is an important competitive advantage. Our politicians did not think so five years ago. Today, they raise this issue all the time, knowing that our age requires it. It is so because people have learned to use reputation when making decisions. If a country’s orientation is to western part of Europe and it wants to belong to the club of world’s democracies, it has to answer the question of suitability for power positions of politicians with a bad reputation and opaque background. Both in Sweden and in England, a politician who cannot answer all questions clearly when caught in an ambivalent situation has to resign. It is also becoming the rule in Lithuania. Not only our politicians understand this, but the public, too, perceives it as something that is inevitable. I think it is good, since otherwise, it is very difficult to know what to expect when you are swamped by years-long court cases.”

The Day published an interview with former Prime Minister of Lithuania Andrius Kubilius a year ago. We talked about his experience of leading the country out of a crisis. Do you see his policy as a success? Was the fight against corruption a key government priority then?

“The conservative government which Kubilius formed took a very important and high-profile step when it revised governance of public companies. It gave quite a significant result for Lithuania, and it did not go unnoticed. However, that government was not as proactive in the fight against bribery. I remember Kubilius saying that he would have paid attention to this problem now, but it is too late, as other people have that job now.

“I am very happy that our government finally pays the fight against bribery in medicine the attention which this problem deserves. We already have an anti-corruption plan, according to which the Ministry of Health needs to reduce corruption in medicine from 24 percent to 10 percent by 2020. This goal, I believe, can be achieved by them. They now have to invent ways of making it happen. However, these are hard numbers which you can go back to in a few years and ask the health minister about his successes on that path.”