Bolshevik coup’s centennial

Russia’s “revolutionary art” as part of ongoing totalitarian propaganda

In the late 1980s, Russia wasn’t sure about officially assessing the 1917 [Russian] revolution. In fact, ex-KGB man and current Kremlin ruler Vladimir Putin hasn’t mustered enough courage up to repeat the main revolutionary slogans. After 17 years in office, his regime is strongly reminiscent of Russia’s monarchy that was overthrown in 1917.

These days, empire-nostalgic Moscow is being aided by the liberal intelligentsia and bourgeoisie in the West, specifically in London, where it has been decided that assessing the Russian revolution can wait. Intellectuals in the West have decided to mark the revolution’s centennial, the path traveled from utopia to the GULAG, by using art, including portraits of Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin, but no portraits of Nicholas II of Russia and his family murdered by the Bolsheviks.

The anti-liberal and anti-bourgeois communists, as well as all those “socialist workers” in the West seem perfectly content with this situation. For reasons best known to themselves, they appear to be unaware of the fact that the Kremlin’s current ideology has nothing to do with communism and keep being at Moscow’s beck and call. The Royal Academy of Arts’ exhibit “Revolution: Russian Art 1917-1932” has been a major cultural event for almost two months, with ads and commercials displayed in double-deckers and Underground. It is also safe to assume that London’s proletariat will not visit the exhibit en masse, considering that the tickets are sold at 16-18 pounds plus transport and other costs.

BUCKETFULS OF BLOOD

Mr. John Milner, one of the exhibit’s curators, readily agreed with me that most of the items on display at the Royal Academy of Arts were undisguised propaganda, but that he would rather describe them as excellent works dating back to horrible times. I told him I thought that portraits of Nicholas II, his family, and house help, murdered by the Bolsheviks, should be displayed, along with the huge portraits of Lenin and Stalin, in order to show the realities at the time. He replied that they could even display bucketfuls of blood, but that this wasn’t the purpose of the exhibit. He sounded reproachful. I said that the pomp served to distract the viewer’s attention from the horrors that had taken place, to which Mr. Milner smiled awkwardly, as though admitting that it was his job to make the project a success.

The items on display are meant to attract each and everyone’s interest. Isaak Brodsky’s Lenin in Smolny (1930) is strikingly photographic and enigmatic, especially the empty armchair. This picture is well known to all who studied at Soviet high schools, but seeing the original explains why those in charge of Soviet propaganda chose it.

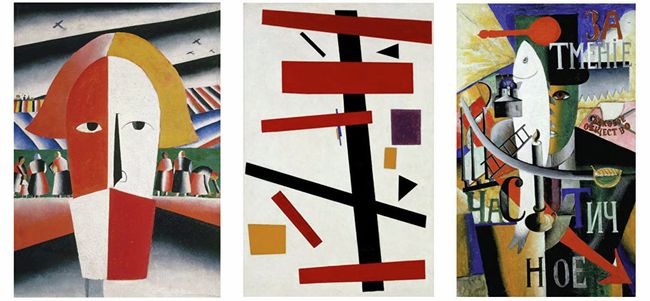

Konstantin Yuon’s New Planet (1921) looks like an illustration for a science fiction novel. There are Kazimir Malevich’s pictures with bright colors and pure forms, Marc Chagall’s flying figures, and Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin’s Bathing of a Red Horse.

FACES OF THE DOOMED

Mr. John Milner said that the excellent works of art on display date back to horrible times, but forgot to mention those on display in the last room, the one the visitors enter before exiting the giant exhibit. This room boasts Soviet photo collages, paintings, and scenes from Soviet documentaries with sports parades. The latter are strongly reminiscent of ones staged in Nazi Germany. There is also a photo portrait of Joseph Stalin that can only be described as sinister. Inside the room, there is a black cube with photos of court rulings, of men and women condemned as enemies of the revolution and communist system being displayed on the inner sides. This is the Room of Memory and I don’t know why Mr. Milner failed to mention it in his interview.

The big question is: What will the visitor remember best after walking out? Several exhibition halls teeming with bright colors and energy or the sinister Room of Memory?

“INTELLECTUALLY LAZY FOR THIS MUSEUM…”

Art critic Jonathan Jones wrote in The Guardian (February 1, 2017): “I came across a room that felt like a pious shrine, a white reliquary containing models of unbuilt architecture, posters for a failed utopia. This was MoMA’s homage to the art of the Russian revolution. Why did it seem so strange? Because here we were on West 53rd street, in the heart of capitalist Manhattan. It struck me as intellectually lazy for this museum, so remote from everything the Russian revolution stood for, to apolitically celebrate its art, as if constructivism and suprematism were just cool aesthetic discoveries rather than utopian projects from an age of struggle and violence. … If the Royal Academy wanted to be honest they might have called it something more like ‘Black Square: The Russian Tragedy 1917-1932.’ The way we glibly admire Russian art from the age of Lenin sentimentalises one of the most murderous chapters in human history. If the Royal Academy put on a huge exhibition of art from Hitler’s Germany there would rightly be an outcry. Yet the art of the Russian revolution is just as mired in the mass slaughters of the 20th century. ... No doubt the [Communist] Morning Star’s art critic will be there in a flash. Me, I will be remembering the kulaks.”

1917 OCTOBER COUP COMMEMORATION GAME

Some believe that this spring’s festival of the Russian revolution in the West is just the prelude, that what will follow will be the more sinister celebration of the Bolshevik coup’s centennial. There is the TUC’s Russian Revolution Centenary Committee, yet one can hardly expect large numbers of TUC activists to attend their events, particularly the jubilee conference, especially people who are versed in the arts and who have visited the gallery exhibits. There will be people like the late British Marxist historian, Eric John Ernest Hobsbawm, member of the CPGB who, when asked in a radio interview why he and his Parteigenossen had failed to condemn mass repressions in the Soviet Union, said simply that they had no such information, adding after a pause that when they had been told about what had happened, they couldn’t believe it, that they probably didn’t want to believe it.

Russia’s “revolutionary art” is part of the Kremlin’s totalitarian propaganda. It is very much alive and kicking. This kind of “art” shouldn’t be admired, rather kept in mind, knowing who has created it, under what conditions, at what price, and for which purpose.

Newspaper output №:

№23, (2017)Section

Topic of the Day