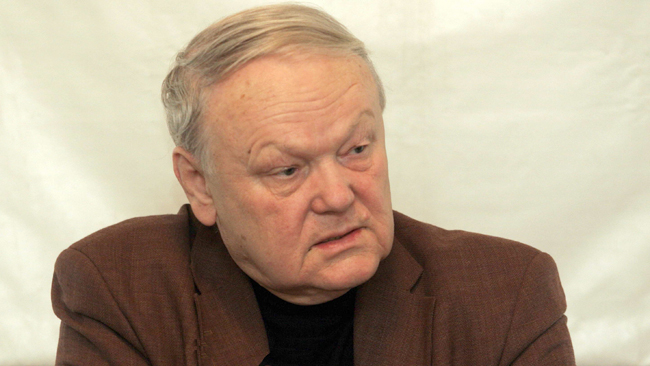

Borys Oliinyk is 80!

His life story is practically a mirror reflection of Ukrainian history over the past 80 years. The Second World War, maturation of the Soviet regime, purges of the cultural elite, Chornobyl disaster, collapse of the Soviet Union, instability, conflicts among its former allies, and the turbulent 24 years of Ukrainian national independence. He has lived through all of this and responded by verse and public activities. He remained an outspoken communist leftist even when events took a course that posed personal danger. He took a firm Ukrainian state-building stand. In May 2008, Den published an interview, quoting Oliinyk as saying, “I am a Ukrainian first and member of parliament second…”

Relying on his long life experience, Borys Oliinyk can easily diagnose all modern social and political ailments. “There are no heroes of mine on that podium [the Verkhovna Rada’s. – Ed.], so I came to join you, not them!” was what he proclaimed from the podium of the first Orange Maidan. Regrettably, his statement holds true ten years later.

In that interview, in May 2008, he made a statement that sounds like a sinister prophesy: “We Ukrainians can operate so well, even brilliantly, in a different, strange system. And we are hard put to build a system of our own, in our own interest… Probably because of this we couldn’t timely plan our national independence strategy, a system of measures that had to be taken – and I mean a system, not a chaotic, nervous search for solutions to problems that keep piling up. One ought to read Lypynsky, Yefremov, Dontsov. Their works outlined our future, even if approximately. When faced with a clear and present danger, we send our young people – actually, children – to the battlefield. Then we knee and pray for their souls…” In a word, he cuts a sophisticated figure. This man is a living reference source of latter-day Ukrainian history, one that can help researchers figure out its whimsical course.

The Editors wish Borys Oliinyk many happy returns of the day, the best of health, creative inspiration, and reaffirm their desire to hear and share with the reader what he has to say on various subjects.

Below are commentaries by Oliinyk’s colleagues, literary critics, friends, and pupils on the role this sophisticated personality has played in Ukrainian culture and history.

ENTHUSIAST, DREAMER AND SAGE

Dmytro DROZDOVSKY, Ph.D. student, Taras Shevchenko Institute of Literature; editor-in-chief, Vsesvit magazine:

“An article on Spanish literature reads that Jose Ortega y Gasset drew lightning to himself the way a big tree does during a thunderstorm. Borys Oliinyk is one of the biggest trees in 20th-century Ukrainian culture. He cuts a controversial figure (well to be expected from any indisputably talented individual). He is an outspoken communist (he holds true the kind of ideals I personally hold for what they are worth: ideals), a knight in shining armor in the Ukrainian cultural domain, a man vested with power, a true poet, a politician who had to grope in the ideological dark, an apologist for the warmth of the human heart and the light of truth. This man has traveled an amazing path in his lifetime. He sought to unite things that rested on altogether different foundations – but only from the standpoint of the proverbial man in the street.

“Borys Oliinyk remains his old communist self, but he is a very special communist, the only kind. Perhaps this is how he should go down in Ukrainian history. The point is that the ‘Moral Code of the Builder of Communism’ contains borrowings from the Holy Bible, many of them, also from German Romanticism. Such lofty ideals were destined to be implemented by ruthless dictators and tyrants their own way (Stalin learned from a fortuneteller that he would become an Eastern Orthodox priest). They all wanted to become political messiahs. Tragically, all those ideas, supposedly meant for the good of man, were carried out by monsters in human form. Borys Oliinyk became a Ukrainian Don Quixote, a sage who can see things the way no one else can. This kind of insight, however, tends to lead one into a maze where one can find oneself even unwilling to find the way out. Borys Oliinyk sees his bright ideals and refuses to see the great damage done by the adherents of the communist system. He is an idealist, a dreamer who sees the shining communist morrow, he doesn’t realize that the communist doctrine is essentially antinational, antihuman. On the other hand, could an orthodox communist proclaim from the rostrum of the 19th CPSU Conference in Moscow, back in 1988, that political repressions in the Ukrainian SSR had started long before 1937, that it was necessary to establish the reasons behind the 1933 famine that had caused the death of millions of Ukrainians, that the names of those responsible for the tragedy should be made public? With that tragedy caused by the Stalin communist regime, there was the communist zealot, Borys Oliinyk, defending all those who had fallen prey to the Soviet collectivization campaign. He was defending fellow humans, human understanding, human rights.

“To figure out this turbulent world, often smeared by politicking, one has to cope with the forces of Evil. Precisely what the Soviet and post-Soviet politics have been all about from day one. Borys Oliinyk was ostracized by colleagues, but he was now a philosopher determined to preserve Ukraine, who did not want to rock the boat, who wanted to build [a nation state] and rally people round his cause. While doing this, serving what is presumably a noble, one is prone to come close to the abyss leading to hell – I mean dealing with politicos. How can you pass judgment on a fellow human who really loves his Fatherland, his native land, who has been following what he still thinks is the right path, who has spared so many dissenters severe Soviet and even post-Soviet legal retribution, let alone persecution? A lot of names come to mind. His memoirs could rate a book on alternative Ukrainian history.

“He was forced to chair the Taras Shevchenko National Prize Committee and reach a compromise with a number of individuals he expressly disliked. The big question is: What would happen to the Shevchenko Prize without Borys Oliinyk? It would have been ruthlessly deformed. I’m personally grateful to him for the ‘Terra Poetica’ International Poetry Festival in 2014, when President Poroshenko was talked into supporting the project.

“There is no denying the fact that Borys Oliinyk is a true Ukrainian. He knows how to rejoice in life; he has empathy, he was the one to help Ihor Pavliuk, currently with Ph.D., who was then forced to spend the nights in a sleeping bag at the Institute of Literature. In a word, he is an enthusiast, dreamer, and sage. He is very straightforward, with an open heart. He feels happy when he can make fellow humans happy – something hard to believe, let alone find among relatives and friends these days.”

LYRICIST STILL TO BE READ BY UKRAINIAN COMMUNITY

Natalia DZIUBENKO-MACE, writer, journalist, widow of Dr. James Mace:

“When discussing Borys Oliinyk as a man, rather than as an author, one tends to refer to his long communist affiliation. He remained true to it even when a number of party functionaries made a political U-turn, building blitz careers under the new democratic mottos while using the good old apparatchik methods. I will never believe that Borys Oliinyk has ever held dear the bulky man-eating communist government machine. Most likely, he never wanted to be in the front ranks of the new flag-waving corruption-rooted patriots. He has never bowed and scraped. For all I know, he is a decent individual revolting against timeservers and timeserving.

“Borys Oliinyk remained a communist even when one could join any other political party, fearing no retribution, and he was a special communist species. He was head of the communist party cell at the Writers’ Union of Ukraine for 11 years. None of the union members was expelled or thrown behind bars during his tenure. He was the one to stop the construction of an industrial facility in Kaniv that threatened the grave of Taras Shevchenko. As a member of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR, he opposed the construction of a bridge across the river Khortytsia. The Soviet bureaucrats had to delay the project. He was the one to hand Soviet Marshal Yazov a letter from the Ukrainian intelligentsia requesting that the premises of the military-political college in Kyiv’s downtown Podil be vacated and used for the reinstatement of the Kyiv Mohyla Academy. Marshal Yazov signed his assent.

“In May-June 1986, he was one of the first to visit Chornobyl and send reports to Central Television in Moscow and the local Ukrainian network. That same year he wrote an article entitled ‘Taking Chornobyl Test’ for Moscow-based Literaturnaya gazeta, exposing the apparatchiks’ criminal timeserving activities. In early July, 1988, he addressed the 19th CPSU Conference in Moscow, dwelling on Stalin’s 1937 purges and said in conclusion, shocking most in the audience: ‘Considering that these purges began in our republic [Ukraine. – Ed.] long before 1937, it is necessary to ascertain the reasons behind the famine of 1933 that killed millions of Ukrainians, name those who were responsible for the tragedy.’ In other words, he was the first to act on an official level, at the Kremlin Palace, back in 1988, and address an issue that would become known as the Holodomor. He proposed to write a ‘White Book’ on the dark deeds of 1932-33. This book was written. He came up with the initiative of preparing and publishing the book Famine-33. This book-memorial contained thousands of eyewitness accounts, compiled by Volodymyr Maniak and Lidia Kovalenko. I was the editor. The names on the editorial board, led by Borys Oliinyk, were deleted from the manuscript shortly before it was to be sent to print. And then it was shelved at the print shop. It appeared in print after the attempted coup against Gorbachev (Aug. 18, 1991). I still don’t know who made the decision, but I know for sure that Borys Oliinyk was among the first to raise the matter of Holodomor on the highest Soviet official level, then in Europe and across the world, as chairman of the Verkhovna Rada’s permanent delegation to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, and later as PACE vice president.

“I first met Borys Oliinyk at the All-Union Congress of Young Writers in Moscow, in 1974. He was there as head of a young and quick-tempered delegation from Ukraine, including Svitlana Yovenko, Liubov Holota, Anatolii Kychynsky, Larysa Khorolets, Bohdan Sushynsky, Natalia Bilotserkivets… That was when pogroms in the Ukrainian literary domain began. Moscow was trying to show that they were taking good care of young talented authors while attempting to assuage political tensions. What was happening was amazing but being done in a youthful spirit, contrary to the party line. Resonant Ukrainian voices were heard. As a resident of Lviv, I found myself being treated in a ‘special way.’ Unlike my colleagues from Kyiv who spoke fluent Russian, I spoke only Ukrainian. When we were having dinner, a group of Russians physically assaulted me, cursing me as a Ukrainian nationalist. I shouted back that they were acting like chauvinists. The situation was getting from bad to worse, but I was rescued by Viktor Astafyev and Borys Oliinyk. They spoke to the men, politely but sternly, and settled the situation. It was with Oliinyk’s blessings that I arranged for an All-Union Writers’ Seminar to be held in Lviv. That was a great occasion. We met and talked with writers from Georgia, Uzbekistan, Lithuania, and Belarus. We would find a secluded spot and discuss matters we would keep to ourselves. Later, our paths crossed in Kyiv, when I edited collections of Shevchenko verse and some of Oliinyk’s books. As an editor with the Radiansky Pysmennyk [Soviet Writer] Publishers, I frequently called him, asking to have the Soviet censors okay a certain book or have an author’s name added to the publishers’ waiting list. He never refused. He always kept his promise. This was very important, especially when it came to Ivan Dziuba’s book, the first one written after a very long pause.

“Our relationships became totally different after James Mace had taken his place in my life. Today you can hear many stories about who and how helped or cared for Jim. I can tell you that Borys Oliinyk helped him with visas and pulled rank to have Jim address international conferences, even the Verkhovna Rada. He would lend Jim a helping hand with all his projects. It was like father and son. On those dark days in May 2004, after Jim’s passing, Borys Oliinyk grabbed his worn portfolio and knocked on every door ‘upstairs,’ called every secure line number only he knew to make the funeral arrangements at the Baikove Cemetery, formally closed as a memorial. He started by telling me it was impossible and then carried out his mission impossible. I will keep thanking him for this until my dying day.

“I regard Borys Oliinyk as a singular lyricist whose creations are still to be read by the Ukrainian community at large. His verse conveys that unique innately Ukrainian message. His is an ironical style, with a touch of Poltava folk humor, complete with the grain grower’s inherent awareness of what is good and true:

My brethren, enemies, scholars,

I shall forgive you all,

I wish you Harvest Home

After a warm rainfall,

But a speck on Shevchenko’s face,

But a broken guelder rose –

This I shall hold in eternal disgrace!”

Section

Topic of the Day