First and second hetmanates in Ukraine-2

Cossacks and state-builders: a breakthrough into the future

(Continued from the previous issue)

The hetman understood that demanding “customary obedience” from the rebellious peasants, i.e., forcing them to do compulsory service in the previous scope, would mean to drastically narrow the new regime’s social basis. This is why, although Bohdan Khmelnytsky issued protective decrees to the nobility, he did not allow large-scale land ownership in Ukraine and opposed excessive growth of class privileges. All the social groups were to do certain compulsory service in the interests of the state – this applied to both the peasantry and the new aristocracy. The estates granted to the starshyna (senior officers) were payment for serving the Zaporozhian Host, where a person held a certain office (rank). Of course, rank estates did not satisfy the Cossack starshyna which strove to obtain rights similar to those of the nobility in Poland and votchinniks (inherited estate owners) in Russia, but the hetman resisted these intentions.

It is due to Khmelnytsky’s failure to establish a hereditary monarchy that the Cossack state was short-lived. The elective nature of supreme power encouraged the domestic conflict and interference of hostile foreign forces – first of all, Russia and Poland.

The new aristocracy not only supported, but also resisted a monarchic transformation of the hetmanite power. Viacheslav Lypynsky notes that it is the “freedom-loving starshyna” that began to put up timid (at first) opposition to the hetman’s monarchic and dynastic intentions. Conflicts in the starshyna milieu had an immediate impact on the behavior of the “Cossack rabble” which revolted against their colonels on the counter-Polish front. The rebels informed the tsar through the Muscovite agent Zheliabuzhsky that they wanted to serve him and no longer wished to obey their officers who began to challenge the tsarist will. It was the “first swallow” of the Moscow-supported ruining process that finally led to the decline and fall of Ukrainian statehood.

Khmelnytsky did not have enough time to finally reinforce the hetman’s power and turn it into a hereditary monarchic institution. On hearing about a mutiny of A. Zhdanovych-led troops in Poland, the hetman suffered a stroke and died on July 27, 1657 in Chyhyryn. “The centuries-old Ukrainian tragedy – stupid and egoistic anarchism of the starshyna, which was unable to self-organize, and treachery of the ignorant ‘rabble’ – killed the greatest statesman Ukraine had ever had,” Lypynsky concludes. “Khmelnytsky fell victim to the many-faced destructive Boor on our unlucky land in the same way as all those who set a lifelong goal, before and after him, to form the Ukrainian nation and state.”

The monarchic nature of the hetman’s power was supposed to become an important factor of the consolidation of Ukrainian society in the course of the 1648-57 liberation struggle, but this did not occur. In the actual situation, the duration and stability of the Ukrainian political system was essentially undermined. Recognizing the supreme power of a tsar enabled Russian centralism to carry out a never-ending offensive on Ukraine’s traditional national institutions and finally do away with Ukrainian statehood.

The Ukrainian elite’s inability to develop and inculcate in Ukrainian society a national monarchic idea created a void in public awareness, which was filled with Russian monarchism. This situation brought forth the so-called principle of dual political identity, where ethnic feelings bizarrely intertwined with allegiance to the Russian Empire and the Russian monarch. At the same time, the Cossack elite ended up devoid of a clear vision of Ukraine’s prospects for independence. Having joined the Ukrainian national renaissance, the Ukrainian nobility (shliakhta) imposed the autonomy-in-federation concept, in the context of future relations with Russia, on the Ukrainian movement in the 19th – early 20th centuries. This concept was supplemented with the ideas of Western liberalism, sociopolitical views of the Cyril and Methodius Brotherhood, and became central in the ideology of the Ukrainian Narodnik movement and, later, in Ukrainian socialist politics. For a long time, this was a leading trend in the Ukrainian movement, characterized by an inconsistent and half-hearted approach to achieving the ultimate goal of political independence.

Mykhailo Drahomanov, who resolutely fought against “Ukrainian separatism” until the end of his life, continued the autonomy-in-federation tradition of the early Narodnik movement. He was trying to persuade Ukrainian politicians to concentrate their efforts on the democratization and federalization of the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires, which he believed would create conditions for a free national development of Ukrainians. For Drahomanov, the ideas of federalism were in the same line with the European ideals of social equality and political freedom, pushing to the background the idea of national independence. This attitude influenced several generations of Ukrainian politicians who fell captive for a long time to Drahomanov’s vision of the national problem, which is bereft of a clear prospect of struggling for national liberation. “Without having this national ideal in their soul,” Ivan Franko noted, “the best Ukrainian forces drowned in the all-Russian sea, while those who continued to stand their ground, fell into disappointment and apathy. It is beyond doubt to us that lack of faith in the national ideal and the related political consequences was the main tragedy in Drahomanov’s life and the cause of the hopelessness of his political quests.”

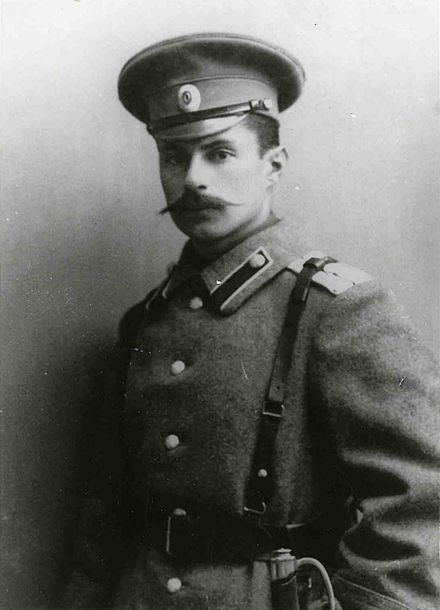

VIACHESLAV LYPYNSKY WAS CONVINCED THAT “THERE HAS NEVER BEEN SUCH A CONSTRUCTIVE, IN TERMS OF THE IDEA AND CONCEPT, ASSEMBLY OF UKRAINIAN PEOPLE AS THE CONGRESS OF AGRARIANS ON APRIL 29, 1918.” IT IS AT THAT CONGRESS THAT PAVLO SKOROPADSKY WAS PROCLAIMED HETMAN OF UKRAINE / Photo from the website wikipedia.org

The absence of clear reference points of Ukraine’s political independence in the Ukrainian elite could not, however, hinder the creation of a strong national-cultural potential, an indispensable groundwork for the national liberation struggle and the existence of a state.

And the 19th century saw the creation of this potential.

The organic resistibility of a considerable part of “the upper crust of Ukrainian society,” as well as of the broad masses of peasants, to Russian assimilative pressure eventually caused independence-oriented trends in Ukrainian society. In 1895 Yulian Bachynsky, a member of the Ukrainian Liberal Party, published a brochure, Ukraina Irredenta, which became a manifesto of the Ukrainian political independence movement. The fact that Ivan Franko appraised this book in 1895 “as a fact of our political life, as a manifestation of national feeling and national awareness” means that this idea had already been high on the agenda in society. He pointed out that “the demand for Ukraine’s political self-sufficiency will come on the political agenda of Europe and will never come off it until it is achieved.”

These ideas of political independence, which can be found in the works of Galician politicians, go hand in hand with the statist concept of Mykola Mikhnovsky in his brochure Samostiyna Ukraina. Thus the idea of Ukrainian independence began to crystallize as a distinct political program on both sides of the Zbruch River. At the same time, as the Ukrainians were becoming aware of the necessity of an independent Ukrainian state, it was more and more clear to them that Ukraine should develop a class-differentiated structure as a prerequisite for an optimal national and political existence. In its turn, a full-blooded national development was supposed to remove social destruction caused by national oppression.

To overcome a simplified view of Ukrainian society, it was necessary to address a higher-level problem – sociopolitical and national reanimation of the higher societal strata of Ukrainian origin, which had thitherto been standing on the Russian or Polish political grounds. At the turn of the 20th century, it was insufficient for the Ukrainian nobility to display a simplified “love for the people” and “love for the peasantry” and spread populist ideas – nobles were expected to take part in the Ukrainian movement, making use of their corporate and class qualities, political experience, and the gift of constructive labor for the state’s sake.

Taking a full-fledged part in the Ukrainian movement, being aware of its exclusive public role, and duly assessing the national creative tradition, this stratum was to have helped overcome certain one-sidedness in the sociopolitical guidelines of Ukrainian citizens.

What brought about an essential shift in the Ukrainian conservative milieu was the activity of Lypynsky who made a major contribution to the ideological an organizational consolidation of this class in the Ukrainian movement. At the same time, Lypynsky resolutely broke with the tradition of branding “lords” as enemies of the people. In his opinion, coming back to their national “ego” from the Russian and Polish camps, they brought their cultural, economic, and administrative experience, intellectual and material values into the process of Ukrainian renaissance, essentially reinforcing the positions of Ukrainian citizens.

Throughout the 19th century, the Ukrainian aristocratic class underwent a difficult and contradictory process of national reawakening on both sides of the Zbruch. The proof of this were, particularly, changes in the socio-national awareness and political orientation of representatives of the ancient Ukrainian noble and magnate families of Puzyn, Sanhushko, Sapiha, Shumliansky, Sheptytsky, Fedorovych, et al. in Galicia. In Greater Ukraine, the Halahans, Tarnavskys, Miloradoviches, Kochubeis, Tyshkevyches, Skoropadskys, Khanenkos, Lyzohubs, and others underwent a similar evolution. Despite the monopoly of liberal democracy and socialist trends in the Ukrainian movement, this evolution of the nobility’s public awareness showed an aspirations for balancing value-related ideological and political attitudes in the Ukrainian movement and a desire to overcome what Lypynsky called “fatal one-sidedness of the nation” caused by the weakness of its right conservative wing.

Interesting in this connection is the appraisal of the political behavior of Galician aristocrats in the joint Ukrainian-Polish section at the Prague Slavic Congress in 1848 by Antoni Zygmunt Helcel, the chief figure of the Krakow school of Polish conservatism. “A half of the Galicians are Ruthenians,” he noted. “Therefore, Slavophiles are supporting again the intentions of these Ruthenians to break away from Galicia and constitute a new Little Russian state composed of parts of Poland, Russia, and Hungary.” What also confirms the attempts of the Ukrainian historical aristocracy to play an independentist role in the political process is the intention to bestow the royal crown of a “Kyivan Kingdom,” planned by Eduard Hartmann and Otto Bismarck in the 1980s, on Prince Lev Sapiha. In the years of World War One, the idea of a constitutional monarchy formed the basis of the political platform of the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine that consisted of politicians from both Galicia and Greater Ukraine.

The emergence of a monarchic concept in Ukrainian political life meant that liberal democracy, Narodnik and socialist trends in the Ukrainian movement were gradually losing their monopoly. This showed that Ukrainian society was able to adequately respond to the challenges of time and was seeking a balance of value-related ideological and political attitudes.

National radicalism of most of the participants in the Ukrainian movement alienated the conservative-minded Ukrainian nobility, a part of which found themselves in Russian monarchic organizations and parties. However, this departure of the nobility was not final – rather, it was a step aimed at self-preservation and protection of their socioeconomic interests. The conservative forces that were not declassed, although they broke with the Ukrainian liberal radical movement, did not lose their national instinct which particularly made itself felt after February 1917.

GERMAN KAISER’S TROOPS IN KYIV, 1918. PAVLO SKOROPADSKY SAYS IN HIS MEMOIRS THAT IT WAS VERY LIKELY THAT, IF THE HETMANATE HAD NOT BEEN PROCLAIMED, THE GERMANS WOULD HAVE MADE UKRAINE AN ORDINARY GOVERNORATE GENERAL WITHOUT ANY RIGHTS / Photo from the website vakin.livejournal.com

The activation of the main conservative components of the Ukrainian countryside – the nobility and the well-to-do and medium-scale peasantry – proved the vitality of the hetmanite tradition in Ukraine. One of many slogans at the thousands-strong Ukrainian manifestation in Kyiv on March 19, 1917, was unexpected for the then leaders of the national movement: “Long Live Independent Ukraine with a Hetman at the Head!”

This activity prompted Lypynsky and other representatives of organized conservatism in Ukraine to search for viable political structures that could resist the ever-deepening class confrontation and challenge the Central Rada’s policies, particularly in agriculture and state formation. It is first of all about the Ukrainian Democratic Agrarian Party (UDAP) and the All-Ukrainian Union of Landowners.

By contrast with the autonomy-in-federation program of liberal democrats and socialists, the UDAP set itself a goal to struggle “for the political sovereignty of the entire Ukrainian people all over Ukraine.” This demand was “the most important reference point of our [UDAP’s. – Author] program.”

What brought about essential shifts in the Ukrainian conservative milieu was participation of Pavlo Skoropadsky and the Ukrainian People’s Hromada he set up in the political struggle. The Hromada was supposed to unite “all owners, irrespective of the shades of color, in the struggle against destructive socialist slogans.” Skoropadsky set a goal – contrary to the positions of traditional Ukrainian political parties – to carry out a program of transformations that was devoid of demagogy and populism and was aimed at building a socioeconomic system based on private property as a foundation of culture and civilization.

After the Peace Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed and German troops were invited to Ukraine to fight Bolshevism, the political doctrinairism of Central Rada leaders brought the UNR to a political and economic abyss. The German military command less and less reckoned with the Central Rada’s weak institutions and was establishing an occupational order. Failure of the government to cope with the situation in the country and stop the chaos caused by the land socialization law eventually endangered the very existence of Ukrainian statehood and did not rule out the likelihood of declaring German-occupied Ukraine a part of Russia. Skoropadsky was very well aware of this. He wrote in his Reminiscences, appealing to “those who call themselves Ukrainians”: “Remember that if I hadn’t taken power, the Germans would have placed an ordinary governor-general in Ukraine a few weeks later. This would have been quite in line with the occupation and, naturally, would have had nothing to do with Ukrainianness.” The disarmament of the “Blue Coat Division” by the Germans was a warning to Ukrainian statehood.

In this connection it is worthwhile to criticize the attempt to make Ukrainian society believe that centuries-old democratism and rejection of authoritarian institutions of power, which run counter to national mentality, are allegedly inherent in Ukraine. Incidentally, authoritarianism is in no way a despotic institution of power and is often a viable method of establishing positive social trends, an important consolidating factor. This fully applies to the Khmelnytsky era, when the hetman’s government carried out a number of extremely important social transformations. It is particularly about Cossack land ownership which was based on waged labor and, accordingly, was bringing about bourgeois relations in Ukraine. It is also worth recalling the great importance of Khmelnytsky’s efforts to rally Ukrainian society around the hetman.

The situation in Ukraine in the spring of 1918 showed inability of the Central Rada, guided by the programs of political parties, to perform a consolidating function for Ukrainian society. This mission could only be accomplished by an uncommon personality who was not guided by socialist slogans but was prepared to realize the positive historical tradition of state-formation in the new conditions. Pavlo Skoropadsky was this kind of political leader, for he was closely linked with the hetmanite tradition and its most prominent bearers – the Cossack starshyna families of the Kochubeis, Miloradoviches, Miklashevskys, Tarnovskys, Apostols, Zakrevskys, et al. On his initiative, a congress of agrarians was convened in Kyiv on April 29, 1918, which announced restoration of hetmanship and establishment of the Ukrainian State.

Analyzing the social ground on which the Ukrainian State emerged, Lypynsky noted that the April 29 congress was attended by grain-growers, mostly descendants of the Cossack starshyna, “the most senior politically and the most experienced stratum in the given historical minute.” They were joined by “the most businesslike and wisest part of the Ukrainian medium-scale peasantry.” But Lypynsky also points out that the clergy, the Ukrainian-born career officers of the Russian army, industrial, financial, and commercial circles, and a part of the intelligentsia, were also taking interest in the congress, although they did not participate in it directly. Therefore, the Congress of Agrarians represented the most influential economic, political, and cultural strata of Ukrainian society at that time. “If we do not take into account the time of the flourishing Kyivan Rus’-Ukraine,” Lypynsky wrote, “there has never been such a constructive and far-reaching, in terms of the idea and concept, assembly of Ukrainian people as the Congress of Agrarians on April 29, 1918.”

The scholar focused his attention on the fact that, for the first time in Ukrainian history, the source of power “proceeded out of tradition, not out of a rebellion,” and “the word ‘Ukraine’ began to mean something of a whole in all the strata and classes – not just one ‘appanage’ of society or just one of its ‘faiths.’” Hence, the very list of the “creators” of the Second Hetmanate showed that there were prospects for the formation of a consolidated society in Ukraine and the cessation of social destruction on the grounds of class and interethnic struggle.

Despite the boycott of Ukrainian socialists, a very short (seven and a half months) existence of the Hetmanate was filled with an extremely intensive and fruitful formation of a Ukrainian state. This process embraced all the spheres of public existence – from the foreign policy, military buildup, administrative or land reform to opening Ukrainian universities and the National Academy of Sciences, and restructuring the Ukrainian school system.

Well acquainted with the practice of public administration in tsarist Russia, Skoropadsky knew that it would only be possible to cement Ukraine’s independence in spite of the destructive forces if the state managed to form a battleworthy regular army and the state apparatus, establish diplomatic relations with as many states as possible, revitalize the economy and finances, and introduce the public funding of educational, research and cultural institutions.

Skoropadsky was creating Ukrainian statehood under extremely difficult and contradictory political circumstances. They demanded clear and concrete actions to form various governmental institutions. And many of them were established in a very short time – in fact from scratch. By contrast with Ukrainian socialists, who pronounced catchy slogans instead of doing concrete work, Skoropadsky was guided by pragmatism aimed at restructuring the state in earnest. His success was caused, to a large extent, by an effective job-placing policy which made it possible to recruit officials not on the basis of their party affiliation or ethnicity but, first of all, on the basis of their professionalism and true attitude to Ukraine.

This approach made it possible to form the state apparatus on a regular and efficient basis. Ministries were organized and manned very quickly, Ukraine was rationally divided into governorates and districts administrated by starostas. As a result, all the laws and instructions of the central bodies of power were much more effectively observed in the provinces instead of remaining declarative acts, as was usually the case with the Central Rada.

The establishment of the State Bank and the Land Bank, the streamlining of the budgetary process, the extremely rapid creation of a stable monetary system, and a high exchange rate of the Ukrainian currency (60 percent of the golden franc) helped revitalize the financial system and the entire socioeconomic life of the country.

On June 22, the military administrative personnel began to undergo essential changes. It was planned to establish a system of military schools to train officers of all branches of service, and the State Military Academy began to be organized. The law on compulsory military service was announced on July 24. Under the law, 85,000 men were to be mobilized in October 1918 and another 79,000 by March 1. A 5,000-strong Guards Division – supposedly, the model of the future Ukrainian army – was formed in July.

By all accounts, the formation of the Ukrainian armed forces in the Hetmanate was put on a regular basis, and it was based on the latest military achievements of the then civilized world.

Yurii Tereshchenko is a Doctor of Sciences (History) and a professor

(To be continued)

Newspaper output №:

№29, (2018)Section

Topic of the Day