Public icon

Viktor SHYSHKIN: “I’d suggest that those who are drafting amendments to our Fundamental Law first read Pylyp Orlyk’s Constitution five times”

The Constitution of Ukraine was ratified on June 28 nineteen years ago. Off and on over the past years the need to make amendments has been discussed. Amendments were made in 2004, in the aftermath of the Orange Revolution; in 2010, under President Viktor Yanukovych (involving the Constitutional Court), and in 2014, after the Euromaidan. Further amendments are being worked out by the Constitutional Commission of the President of Ukraine. What is wrong with the Fundamental Law? Why should it be amended? Below Viktor SHYSHKIN, one of its authors, currently justice of the Constitutional Court, shares his ideas concerning this issue, also the reform of the courts and prosecutors, and the high-profile Gongadze-Podolsky case.

Not so long ago we watched Samopomich faction leader Oleh Bereziuk ask ex-President Leonid Kuchma to sign a copy of the Constitution in parliament. He later explained that he’d done that for his lawyer friend, considering that the Constitution’s ratification in 1996 was to be credited to the second president. Indeed, there is a story about Kuchma allegedly forcing the MPs to vote for it on that “Constitutional Night.” The question is: What did actually happen, considering that you are one of its authors and were present then as a member of parliament?

“First, the Constitution is a political and legal document. It reflects the political doctrine, the development of our society and our state. Second, the allegation that the Constitution was ratified overnight is an overstatement, mildly speaking. In fact, nothing could be further from the historical truth. Let me remind you that the Constitutional Commission (I was its deputy chairman) was formed in 1991 and the Constitution was adopted in 1996. In other words, the constitutional process lasted for several years and involved various working groups. As a result, nine drafts were prepared, including by a number of political parties, among them the Christian Democratic, the Communist, and the Socialist Party. The main setback at an early stage was that different parties held different views on the Constitution.

“Also, the Verkhovna Rada of the first convocation had 75 percent communist MPs. The percentage was officially lower in the second convocation – simply because many communists had parted with their membership cards. MP Ruslan Bodelan, for example, was not listed as a communist in the second parliament, although everyone knew that he had held the post of the first secretary of the Odesa regional party committee. Therefore, it is safe to assume that the first two parliaments were dominated by the communists. Under the circumstances, it was impossible to adopt a true national democratic constitution. One had to find a compromise, a draft that could serve as the basis of the Fundamental Law. By the way, on the night of June 27-28, 1996, more than 40 articles of the Constitution had been agreed upon during the previous two weeks, so the casus belli was in the articles on the language, land, property, and political system, including the Autonomous Republic of Crimea. Frankly speaking, I was against the autonomy back in 1991 and now we can see the outcome. We could have made do with a Crimean Tatar autonomy rather than that of the entire peninsula.

“About the then president. Leonid Kuchma may have acted as a catalyst at a certain point, but he never played a major or outstanding role in the [constitutional] process, and forget about forcing anyone [to say yea] on that ‘Constitutional Night.’ In fact, the Supreme Council of Justice of Ukraine was formed on the model of the Conseil Superieur de la Magistrature (Higher Council of the Judiciary) of France. MP Novykov and I had come up with the idea. In France, the Higher Council is headed by the President and we proposed the same in Ukraine, but the MPs hated Kuchma’s guts and deleted the clause at the last moment.

“If I were that MP who asked Kuchma to sign a copy of the Constitution, I wouldn’t have mentioned Kuchma’s outstanding role in its enactment. One shouldn’t spread myths like that. Kuchma actually had nothing to do with the working out of the current Fundamental Law. Mykhailo Syrota and Vadym Hetman did, God rest their souls. Kuchma didn’t even know that the Constitution would be on the agenda. When he learned the news, he got so scared he raced to the Verkhovna Rada in time to watch us adopt the closing chapters. It was [Speaker] Oleksandr Moroz who said no one would leave the premises until after voting on the Constitution. He even ordered the MPs who weren’t in attendance summoned to the Verkhovna Rada.

“I might as well tell you that my only government award is the title ‘Merited Lawyer of Ukraine’ conferred on me in recognition of my contribution to the drafting of the Constitution. That’s what the presidential edict reads, signed by Kuchma who knew I was his enemy.”

The newly adopted Constitution had a good press as one of the best in Europe. Is that right?

“The European experts agreed that it was a quality document. The French said we had made the best kind of the Higher Council of Justice – they knew what they were talking about, being the founding fathers of such institutions – in the sense of representing various legal strata. Our Supreme Council of Justice is made up of seven ‘flows,’ with six being formed by election and the seventh an ex officio one. There are no analogues. The only critical remark the French made was that our society is not yet mature, that the Soviet hangovers are still strong, and that we may fall prey to our own wishful thinking. And that was precisely what happened. Remember Comrade Serhii Kivalov’s antics? Our draft was absolutely correct in terms of doctrine. It was a good constitution. However, we all know that our biggest problem is learning to implement it instead of constantly changing it. Look at the Americans. They haven’t changed their Constitution, only amended it. Amending is not changing articles.”

The Brits recently marked the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta which isn’t a constitution but which they have used as one for hundreds of years. What’s the secret?

“The secret is that they adopted what is theoretically known as the social contract. They simply agreed among themselves to carry out their decisions. The Brits raise their children to treat the written law with respect. Of course, they’ve had problems, some of their kings wanted laws written to serve their interests, but society wouldn’t let them. Sir Winston Churchill said, ‘When our kings are in conflict with our constitution, we change our kings.’ This is precisely the task facing our society, considering that whoever comes to power wants to change the Constitution. This was practiced by the Soviets when each general secretary [of the only ruling communist party] would adopt or prepare a constitution of his own; very much the same is being practiced in independent Ukraine, with each president trying to make changes to the Fundamental Law. Constitutional commissions have been set up by Viktor Yushchenko, Viktor Yanukovych, and Petro Poroshenko. Do we need these commissions? Let’s first learn to carry out what is already written and then make changes if we really have to.”

What’s at the root of this problem?

“Bad legal manners. We fail to see the Constitution as a public icon – and this is precisely how it should be regarded. If changes are in order, they must be made very carefully. It was with reason that the authors of the Constitution set forth such complicated amending procedures in HYPERLINK "http://www.rada.gov.ua/const/conengl.htm" \l "r13#r13" Chapter XIII. Haven’t the Americans had their own problems in that department, including the Watergate scandal when Richard Nixon was impeached, and when Bill Clinton found himself on the verge of impeachment?”

Objectively speaking, does Ukraine have to change the Constitution?

“Probably, if we’re talking unbalanced branches of power. The 1996 Constitution provided for a balanced political system, except that not all wanted to adhere to it. The thing is, whatever you write, if there is someone who wants to grab the biggest piece of the pie, no organizational formulas or statutory acts will stop him. Changes to the Constitution in 2004 caused a degree of imbalance in the President-Cabinet-Parliament triangle of power. To be frank, back in 1991 when we chose presidential-parliamentary governance, I didn’t like it. I am a Germanophile, so I prefer the parliamentary system, with the Federal Chancellor, Federal President, and Parliament, with each and everyone acting in accordance with the Constitution, with no one trying to grab the biggest piece of the pie. No one has tried to destroy the foundations of government in Germany the way it has been done in Ukraine. I welcomed the changes to the Constitution in 2004, in terms of doctrine, but I also criticized the way they were drawn up and enacted because it ran counter to set procedures. In 2006, after Yushchenko was stripped of some of his presidential powers, he set about inventing various [legislative] techniques. The current situation also makes me wary. Could Petro Poroshenko be following in his footsteps? I wonder whether those who are drafting changes to the Constitution now will comply with them afterward.”

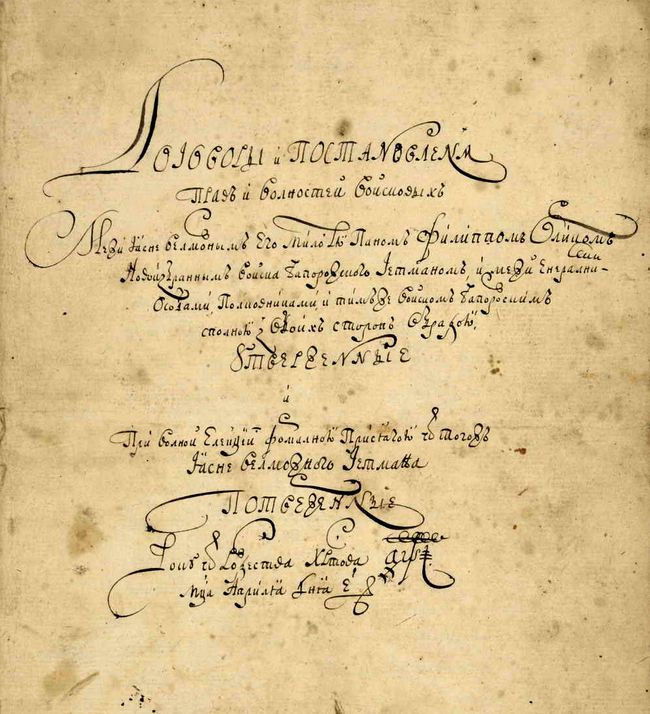

There are different views on the legal document Pylyp Orlyk drew up back in 1710. Do you think it could be regarded as the first Constitution of Ukraine?

“I do. No one says that such a document must have the kind of format we’re used to these days. Proceeding from its main clauses, Pylyp Orlyk’s document can be regarded as a constitution. The language and style may not meet the modern standard, but the same is true of the American Constitution. One ought to consider the stages in scholarly progress. Pylyp Orlyk’s Constitution was drawn up relying on the intellectual potential of society at the time. The document actually has an article on legislature (the Cossack Council), one on the president (Hetman), and one on the judiciary (Justice General). The Hetman, among other things, had no right to meddle in the affairs of the Justice General. We find a similar clause in the American Constitution that was written 70 years later. The 1710 Constitution also provides for social rights. For example, the children of fallen Cossacks were to be sustained by the Zaporozhian Host. There are anticorruption clauses, too. I’d suggest that those who are drafting amendments to our Fundamental Law first read Pylyp Orlyk’s Constitution five times. The hetmans of Ukraine were well-educated individuals, graduates of reputed universities who knew five to six languages.”

JUNE 28, 1996. IN FRONT OF THE VERKHOVNA RADA BUILDING / UKRINFORM photo

You are being critical of the current Constitutional Commission. Why?

“Because it’s a fake. They can beat the bejesus out of me for this, but that’s what they’re all about to me.”

Are any of the commission members having consultations with any justices of the Constitutional Court to avoid further problems or inaccuracies? Is there cooperation?

“There is, involving retired CC justices, including, from what I know, Mykola Koziubra and Ivan Tymchenko. No current justices can be involved. We have no right to be involved.”

The Constitutional Court is known to have passed rulings that seriously damaged its reputation. In 2010, the CC helped Viktor Yanukovych reinstate the 1996 Constitution. Any comment?

“I have a dual attitude to the 2010 CC ruling. On the one hand, I believe that the 2004 law amending the Constitution had to be nullified because it had been enacted counter to constitutional procedures. The Constitutional Court established the fact and passed the right kind of ruling. But if it had had the guts to proceed to abolish the bills passed by the MPs who rigged the vote, this would have made things much better, considering that they had actually violated the constitutional voting procedures. No matter how many MPs pressed the yea or nay button; if a single one breached the voting procedure and it was an established fact, the entire vote should be invalidated, even in the presence of 245 MPs’ responses.

“On the other hand, the CC failed to determine who should do what under the circumstances. In my judicial opinion [dissent] I stressed this failure, but the Court passed a different ruling. The politicians took advantage of that ‘quilted’ constitutional approach. Even though the CC never authorized the Presidential Administration to publish the 1996 Constitution, Minister of Justice Volodymyr Lavrynovych did just that. Clause 3 read that all executive bodies had to bring legislation into conformity with the ruling of the Constitutional Court. The CC ought to have specified that, should the Verkhovna Rada put a resolution to the vote, it would have to do so in keeping with the constitutional procedures.”

Our Prime Minister Arsenii Yatseniuk said even before his appointment that the Constitutional Court should be disbanded and its authority transferred to the Supreme Court. Other politicians have made similar statements.

“Such statements are irresponsible. They are made out of either infirmity or ignorance. Churchill said they change their kings, not their constitution. Therefore, politicians who do not understand the construction of government should be replaced. One has to be familiar with jurisprudence and works by 20th-century European lawyers, among them the Austrian jurist, Hans Kelsen, the founding father of constitutional justice. By the way, his grandparents came from what is now Lviv oblast. Constitutional justice must be kept functional. Under the continental European doctrine, the Supreme Court cannot discharge the functions of the Constitutional Court because the former is tasked with acting in accordance with – and applying – the law while the latter passes judgment on the law. A single court can’t discharge all these functions. That’s at the root of the Kelsen Doctrine presently accepted all over Europe, even in Central Asia (exactly how it is being applied is a different story).”

Are the politicians exerting any influence on the Constitutional Court? If so, how do you feel about that?

“They are and the recent early replacement of the CC membership is proof enough.”

Recently, the Constitutional Court issued findings on the constitutionality of the bill on amendments to the Constitution regarding the immunity of MPs and judges, precisely whether it ran counter to Articles 157 and 158 of the Constitution, as requested by the Verkhovna Rada. The findings read that the bill did not. We know that you issued your judicial opinion. Would you care to describe it?

“Section 2, Article 157, reads that the Constitution cannot be changed in conditions of martial law or in an emergency situation. Of course, martial law or an emergency situation are the President’s prerogative; his edict to that effect is subject to approval by parliament. However, Section 2, Article 157, indicates not the fact of the President’s proclamation of martial law or an emergency situation, but the presence of circumstances under which this proclamation can be made. A tentative list of circumstances for imposing martial law is found in Article 1, Law of Ukraine “On the Legal Regime of Martial Law” (enacted May 12, 2015), namely: (1) the presence of an armed aggression or a threat of attack on the government; (2) a threat to the national independence of Ukraine and its territorial integrity; (3) vesting relevant public authorities, military command with the powers required to address the threat and ensure homeland security; (4) temporary restrictions on the constitutional rights and freedoms of citizens and the rights and legitimate interests of legal entities, effected when faced with aggression or a threat of attack on Ukraine; (5) timeframe of the restrictions.

“All these circumstances are present in Ukraine, except that partial mobilization could be added in the face of Russia’s undisguised aggression against Ukraine. Several rounds of this mobilization have been carried out, on the President’s orders. The Constitutional Court doesn’t have to consider the presence/absence of such executive orders to issue a ruling on the presence of circumstances warranting martial law. Martial law can be imposed considering that (a) the Russian Federation invaded Ukraine, occupying and then annexing the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, also the city of Sevastopol as part of its territory. The Russian Federation’s authorities, namely the President, Parliament, and the Constitutional Court, took part in the annexation procedures by issuing pertinent acts. This is evidence of the presence of one martial law component; (b) there are a number of political appeals and statements, legislative and statutory acts by public authorities that testify to the fact of an armed aggression on the part of Russia and a clear and present danger to the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Ukrainian state; (c) it was in the presence of circumstances warranting martial law, rather then after passing the bill, that the Verkhovna Rada resolved to consider the possibility of imposing temporary restrictions on human rights in Ukraine.

“In view of Russia’s armed aggression against Ukraine, involving regular Russian troops and unlawful units of militants formed, controlled, and funded by Russia, the Ukrainian parliament passed an unprecedented resolution on May 21, 2015, announcing that Ukraine, faced with foreign aggression, had to make a derogation from the obligations assumed by it as a signatory of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, namely from Articles 5, 6, 8, and 13 thereof. In peacetime such a resolution by the Verkhovna Rada would suspend or even terminate Ukraine’s Council of Europe membership for failing to meet its commitments. Relying on the above analysis of the legal framework made up of the statutory acts submitted by public authorities after Russia had invaded Ukraine and annexed Crimea (an internationally recognized part of Ukrainian territory), the Constitutional Court had enough legal opportunities to systemically and objectively assess the situation that had developed and recognize the presence of circumstances warranting martial law and denying the possibility of amending the Constitution of Ukraine.”

You are the first Prosecutor General of independent Ukraine. How do you feel about the reform of the public prosecutor’s office? The pertinent bill has been twice put off in parliament, the last time until July 15, 2014. What’s the problem? Do you think this bill will actually help change that office for the better?

“Honestly, I haven’t read the bill, but you can leaf through the copies of Vidomosti Verkhovnoi Rady [Verkhovna Rada News] of the 1990s. You’ll see that our parliament would first pass a resolution approving the concept of a bill, showing us the direction, and then the bill would be actually prepared. Today those who draft the laws don’t seem to know what they’re writing about. I haven’t seen the concept of a new public prosecutor’s office; I have no idea what role it will be assigned in our legal and political system. There are two models of this office in Europe, the French and the German one. The Russian and the Soviet empires practiced the German model. It was undemocratic but there was a certain structure. I mean we have first to determine the concept. If it is French, then you will be part of the judiciary (the Higher Council of the Judiciary in France has jurisdiction over the prosecutors); if it is the German model, you will take orders from the Ministry of Justice. The same is true of the American model. What about our public prosecutor’s office? I have no idea.”

How do you assess our parliament as an MP of the first three convocations?

“No offence meant, but from the standpoint of professionalism, the way they prepare bills, I’d grade their performance D minus.”

After the years, after various events in Ukraine, could you say that this country is getting closer to the rule of law?

“I don’t think so. Rubber-stamping laws does not indicate the presence of a country ruled by law. Among the indicators should be true justice and knowledge of law. We have lots of law schools that produce lots of graduates, but to little avail. We have no quality law schools. There is little knowledge of law. Why are our courts of law packed with cases still to be heard? Because our officials know next to nothing about law; they lack proper training. And so our citizens keep filing their complaints with the Strasbourg Court.”

The judiciary reform is one of our highest priorities. Much has been said and written about it. Our parliament has repeatedly adopted changes to legislation and we’ve heard from four MPs and experts that this will essentially improve the situation. No such improvement with the passage of time, with most courts remaining at someone’s beck and call, corrupt. As a professional, do you think that we are moving in the right direction? What kind of reform do we really need?

“The problem with our courts of law is not organization, considering that the Constitution and pertinent laws are correct. The problem is judicial personnel, selecting and appointing bona fide professionals. I’d be hard put to say whether the High Qualification Commission of Judges of Ukraine is helping with this problem. My professional experience says the root of the problem is right there – and the same is true of the manpower policy in Ukraine.

“Several months ago I got in touch with the Presidential Administration and requested an appointment with the head of state. First, I had become a member of the Constitutional Court as a presidential appointee. Second, my tenure was expiring in six weeks. I haven’t heard from the PA to this day. The President could’ve publicly declared something like Mr. Shyshkin’s tenure is nearing its end, so I propose the following replacements and I would like to hear public opinion. Perhaps you have your own nominees. That’s what glasnost, contact with the people, is all about. That’s what we don’t have. Another problem with the judiciary is found in the process per se, especially when hearing criminal cases. Administrative cases, lawsuits are more or less OK. But the Criminal Procedure Code (prepared by our working group) was mutilated owing to the dedicated effort of Comrade Andrii Portnov. By introducing his changes he created problems for both the investigators and judges. All these mistakes have to be rectified.”

The Gongadze-Podolsky case is a graphic example of the inadequate status of our law enforcement and judiciary. The Kyiv Court of Appeal has for the past two years been preparing to hear the appeals regarding the life sentence of the chief perpetrator in the case, ex-General Oleksii Pukach. In a recent hearing, victim Oleksii Podolsky’s representative in court, Oleksandr Yeliashkevych, requested that the court summon Justice Viktor Shyshkin of the Constitutional Court as an expert. This request made headlines. What is your stand in the matter?

“First, in the fall of 2000 I was deputy chairman of a parliamentary commission tasked with investigating high-profile crimes, including the attacks on MP Oleksandr Yeliashkevych of the second and third convocations, public activist Oleksii Podolsky, and journalist Georgy Gongadze. Of course I have a stand in the matter, particularly in regard to the CC ruling in 2011 – I mean the admissibility of evidence in court. Oleksandr Yeliashkevych had contacted me on that issue. Also, I had something to say in court concerning the Podolsky-Gongadze case. The two crimes were interrelated and so they were made a single case. There are Melnychenko’s tapes and the chief perpetrator in both cases, Oleksii Pukach.

“However, the problem was not only the CC ruling (it could be defective, like some other rulings because of political bias), but also the way we had placed certain clandestine agencies under control, including surveillance. By way of example, compare Melnychenko’s tapes with a DVR any car driver can have. Can DVR data serve as evidence in court? It can. Then why not Melnychenko’s audio tapes? They should be allowed as evidence, the way the footage of the Maidan massacre was allowed. How do you distinguish between authorized and unauthorized evidence? DVR data is unauthorized yet legally acceptable evidence, considering that an ordinary car/truck driver doesn’t work for a law-enforcement or clandestine agency. But evidence provided by any such agency is accepted only if authorized (previously by a public prosecutor’s office, now by a court of law). In other words, such agencies are kept under control lest they use their authority for their own or someone else’s benefit. The next question is: Who bugged the President’s office? Melnychenko? Did he have the authority? If he didn’t, he ought to have requested authorization. Surveillance wasn’t part of his duty. Consequently, he didn’t require such authorization. Consequently, he hadn’t violated any laws. Consequently, his audio tapes could be used as evidence in court. Moreover, the court had to assess that evidence because it was as good as an eyewitness testimony.”

This high-profile criminal case is still to be resolved, despite the repeated changes in government, Prosecutor General’s Office, judicial board. Nor have the findings and recommendations of the parliamentary commission (of which you were a member) been complied with. Most importantly, those who ordered the crime haven’t been brought to justice. Why?

“Because many individuals – the powerful of this world – were involved in or with these crimes. Leonid Kuchma wouldn’t want to see this case solved in the first place, because his involvement would become clearly apparent. The trouble is, many other functionaries were involved. Why wasn’t the case solved after the Orange Revolution in 2004, after Viktor Yushchenko became president? Because during the campaign ‘Ukraine without Kuchma’ (in which I took an active part) the activists were condemned by characters like Pliushch and Yushchenko, almost to the point of being accused of having turned traitor to Ukraine; because Yushchenko was also involved with Kuchma. He told Lesia Gongadze he’d see the case finally solved, cross my heart and hope to die, but never did. Parallels could be drawn with some members of the current administration. The Gongadze-Podolsky case is high-profile and multifaceted, involving many people, spelling corruption, falsification, intimidation, newly classified data, new deaths – after all those years no one is willing to solve the case. We’ve repeatedly requested final conclusive tests run on the Tarashcha headless corpse. Our task force had submitted to the Prosecutor General’s Office Georgy Gongadze’s true genetic code, so the body could be properly buried because the situation was getting from absurd to morbidly grotesque. Now is the time for your colleagues, media people, to get active and lend a helping hand.

“Legally speaking, this is just another criminal case, even if high-profile. From the political and social points of view, it is as high as Mount Everest, considering that the outcome will show whether Ukraine can finally cleanse itself and proceed to change for the better or we will continue to waste time, lose parts of our territory, and let fellow Ukrainians die. Tertium non datur – a third is not given. Our government must remember that its attitude to this case is a test of its viability, that the result will affect the future of Ukraine.”

Section

Topic of the Day