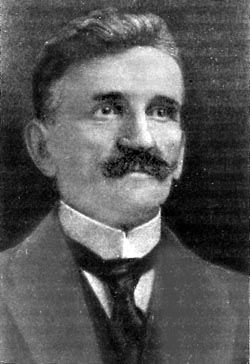

President of “Eastern Switzerland”

Yevhen Petrushevych’s political profile

He was a typical maximalist and an uncompromising politician— hence he followed an unrealistic political course. He is the most tragic figure in Ukraine’s recent history — this is how President Yevhen Petrushevych of the Western Ukrainian National Republic (ZUNR) and his life were described by his contemporaries Lonhyn Tsehelsky and Sydir Yaroslavyn. Indeed, this charismatic politician experienced the joy of the state-building process in 1918-19 and the bitter political fiascos of the mid-1920s.

The future ZUNR leader was born on June 3, 1863, in Buzke, near Lviv, into the family of a parish priest and a dean in the Greek Catholic Church. His father was elected deputy chairman of the county council of Kamianka-Strumylova. He was well-versed in history and literature, embraced a broad range of cultural and spiritual views, and had a keen sense of national identity. He raised three sons and three daughters.

After graduating from the Academic Gymnasium, Petrushevych enrolled in Lviv University’s Law School. As a student, he became one of the leaders of the youth movement and was president of the Academic Brotherhood. After obtaining a Ph.D. in Law, he receiving training under the able guidance of Dr. Stepan Fedak, director of the Dniester Society, and then opened a law firm in Sokal. He proved himself a talented organizer of sociopolitical, cultural, and educational life in that remote county.

He headed the county branch of the Prosvita educational society, organized the Narodny dim (People’s House), was among the organizers of the county’s savings bank, and headed the struggle against the Russophiles who had a fairly strong position in the county of Sokal at the time. He made a name for himself as a lawyer and was favored by the public at large for his skillful defense of their rights against the local authorities’ arbitrary rule.

PARLIAMENTARIAN DEFENDING UKRAINIANS IN GALICIA

In December 1899, Petrushevych joined the newly established Ukrainian National Democratic Party (UNDP). Among his fellow party members were Mykhailo Hrushevsky, Kost Levytsky, Ivan Franko, Yulian Romanchuk, Vasyl Nahirnyi, and other noted politicians.

In May 1907, during the first parliamentary election (after the adoption of democratic legislation in Austria-Hungary), the talented lawyer was elected to the parliament as a representive of the large Sokal-Radekhiv-Brody constituency. He became a leader of the Ukrainian Club (on a par with Levytsky).

In 1913, he was elected vice president, and in 1916, chair of the Ukrainian Parliamentary Representation in Vienna. Petrushevych’s speeches at the sessions were goal-oriented and deep reasoning. He criticized the way the Austrian government handled that nationality issue, constantly drew parliament’s attention to the negligent official attitude to the Ukrainian language and interests of the village poor, and urged for reforms.

In 1909, Yevhen Petrushevych moved his law firm to the highland town of Skole, where he soon became governor. In 1910, he was elected delegate from the Stryi electoral district to the local Galician Diet, the highest elective body in the region. At the first session in September, 1910, he spoke on behalf of the radical wing of Ukrainian delegates as part of a heated debate about the new Diet election bill.

The Oct. 30, 1913 election to the Galician Diet saw 32 Ukrainian delegates get seats in parliament, among them Sydir Holubovych, Ivan Kurovets, Teofil Kormosh, Ivan Makukh, Roman Perfetsky, and Lonhyn Tsehelsky. The Ukrainian Club’s leadership went even further. After receiving the key posts on the commission set up to revise the new law on elections, Petrushevych and Levytsky succeeded in having the Ukrainian quota in the Sejm raised to 62 seats (out of 241). This decision was adopted by the Diet on Feb. 11, 1914.

Furthermore, after years of struggling with the Poles, a resolution was passed to open a Ukrainian university in Lviv. Petrushevych also filed an interpellation concerning the government’s repressive measures against the rural populace and measures aimed at curbing Ukrainian labor emigration. At the time he was often in contact with political emigres from Naddniprianshchyna, members of the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine (SVU, founded Aug. 4, 2008).

Petrushevych was also an active member of the Austrian Parliament. Together with Levytsky, Tsehelsky, and Teofil Okunevsky, he prepared the booklet What Did Our Delegates Do in Parliament? The Manifesto of the Ruthenian (Ukrainian) Parliament Club (1911). It read that the Ukrainian faction found itself in a very difficult situation because it had few members, but that the MPs made every effort to improve the status of the Ukrainian populace and gain respect for it in other groups in parliament and the government.

At the peak of the First World War, Petrushevych took over Levytsky’s post as head of the Ukrainian Parliamentary Representation (UPR). The struggle for Ukrainian interests intensified after the imperial decree of Oct. 23, 1916, allowing the Poles to restore their statehood and actually placing Galicia under Polish rule. This caused a real war between the Ukrainian MPs on the one hand and their Austrian and Polish counterparts on the other. Petrushevych met with a number of influential Austro-Hungarian figures and made several well-substantiated public statements, defending historical justice in regard to Galicia as an ethnic Ukrainian territory and its people, who had the same right to have a nation-state as did other people of the empire.

On May 30, 1917, the head of the UPR made a statement in parliament, demanding that the state of Galicia-Volhynia be restored and the [Austro-Hungarian] government observe the principles of self-determination which can be used by oppressed people. Using strong arguments, including the participation of Ukrainian Sich Riflemen (USS) in the war on the Austro-Hungarian side and the anti-Russian stand adopted by the General Ukrainian Council (ZUR), the Ukrainian delegates led by Petrushevych and Levytsky succeeded, in the fall of 1917, and the persecutions of the Galician populace on the part of government officials and the Polish administration somewhat slackened.

Now more Ukrainians were appointed to important offices on the local and regional level. In fact, Ivan Horbachevsky was appointed Minister of Healthcare (1917-18) and Yosyp Haninchak became Prosecutor General of Austria. They even succeeded in having the pro-Polish General Diller replaced with General Karl Georg, Graf von Huyn as Governor of Galicia, who was known for his more considerate attitude to the Ukrainian populace. Although he opposed Petrushevych in certain important issues, Levytsky had to acknowledge the man’s commendable performance: “Yevhen Petrushevych displayed a great deal of energy in the most trying periods in our liberation struggle. Among the delegates he was on the more outspoken side,” he recalled in 1937.

At the international conference in Brest-Litovsk in February 1918, Petrushevych headed the Galician delegation. Although the latter was barred access to the debate, it facilitated the inclusion of a secret addendum to the treaty between the Central Powers, UNR, and the Bolsheviks. It included Austria’s obligation to grant Galicia an autonomous status before July 20, 1918. As it was, the Polish MPs in Vienna Parliament torpedoed the ratification of the Brest-Litovsk accords that protected Galicia from Warsaw’s encroachments, and were, in fact, a step toward the restoration of Ukrainian statehood there.

Petrushevych responded by working out — in collaboration with Czech and Slovak MPs — a plan for the restructuring of Austria-Hungary and submitted it to Kaiser Karl. His concept was that the empire had to be transformed into a federation of free peoples, with the prospect of creating nation-states in alliance with Austria. On Oct. 16, 1918, the Kaiser signed an edict proclaiming Austria’s status as a union state and the right of its people to self-determination.

TIME FOR CRUCIAL CHOICE

Aware that the Habsburg monarchy was on the verge of collapse, the Galician political leadership, led by Petrushevych, resolved on Oct. 10, 1918, to convene the Ukrainian Konstytuanta (Constituent Assembly, the supreme political council) in Lviv on Oct. 18 in order to decide on the future of their land. On Oct. 19 this assembly, attended by the Ukrainian members of parliament, those of the Galician and Bukovynian Deits, bishops, representatives of political parties, organizations, and societies resolved to form an independent state in the ethnic Ukrainian land, after electing the Ukrainian National Council (UNRada) chaired by Petrushevych. Tsehelsky noted that its members included “intelligent people worthy of their rank and position, wholeheartedly dedicated to their people’s cause. Each was a gifted orator and parliamentarian.” On Oct. 21, Petrushevych addressed a meeting of representatives from all parts of the region in the People’s House and, in the presence of Metropolitan Andrii Sheptytsky, read out his [draft of the] UNRada Statute, explained his plan for a legitimate takeover plan. He took these documents along to Vienna where he tried to speed up the Austrian government’s decision to let the Ukrainians come to power.

UKRAINE IN THE WHIRLWIND OF THE 1918-20 WAR. COMBAT ACTION CHART.

Taking over political power in a peaceful way did not work in Galicia. Lviv’s UNRada delegation, led by Levytsky, and the Military Committee, led by Dmytro Vitovsky, carried out a successful coup d’etat in Lviv (Nov. 1, 1918) and also in Galicia and Bukovyna. A Ukrainian nation-state [Western Ukrainian National Republic, ZUNR] was proclaimed on Nov. 1, 1918. The State Secretariat was formed on Nov. 9. The state-building process spread throughout the region.

The war started by the Poles, the fierce battles in Lviv and Peremyshl, and the revolutionary events in Hungary prevented Petrushevych from going there. Instead, arrangements had to be made for the return of Galician officers and men from the Italian and Balkan fronts forthwith, while persuading Austrian officers to join the Galician army and handling the legal aspects of property left after the liquidation of the monarchy.

He came to Stanislav, where the ZUNR government had moved, only toward the end of December 1918. On Jan. 3, 1919, he presided over the first UNRada session in the concert hall of the Austria Hotel, where the government officials were accommodated. This session unanimously passed a resolution uniting the ZUNR and the UNR. It read: “The Ukrainian National Council, in exercising the right of the Ukrainian people to self-determination, hereby and as of this date, solemnly proclaims the union of the Western Ukrainian National Republic and the Ukrainian National Republic, as a single, solid sovereign National Republic... Until such time as the Constituent Assembly of the Republic is preserved, the Ukrainian National Council shall exercise legislative authority on the territory of the former Western Ukrainian National Republic. Until this time, the State Secretariat, established by the Ukrainian National Rada as its executive body, shall exercise civil and military administrative authority on the said territory.” This fateful document was signed by Petrushevych, Horbachevsky, and members of the UNRada’s Vydil (Executive Board). Toward the end of the session Petrushevych, the newly elected UNRada President, invited council members to “witness a torch march, and when the brass band struck up the march Hei, ne dyvuites, dobrii liudy, shcho na Vkraini povstalo!, there were tears of joy in the president’s eyes.

After the ceremony of proclaiming and adopting the Act of Unity in Kyiv (Jan. 22, 1919), Petrushevych became a member of the UNR Directory, but he wouldn’t take part in any sessions until summer. He met with Symon Petliura on Feb. 27, 1919, in Khodoriv, in the course of the Polish-Ukrainian talks attended by Eugene Bartholome, the head of the Central Powers’ mission. In fact, it was then that their views on Ukraine’s geopolitical course drifted apart. Petrushevych criticized the Chief Otaman who was considering the possibility of drawing the demarcation line along the Buh River and essentally accepting that the Lviv and Drohobych-Boryslav oil basin (yielding five percent of the world output) may be annexed to Poland.

Tsehelsky noted that the UNRada “worked like a real parliament: its members had accumulated experience as members of Parliament, Diett, and county councils under the Austrian rule. The sessions of the Rada were usually open to the public, so anyone could access the public gallery.” As President of the UNRada, Petrushevych more often than not fulfilled representative functions. However, under the Interim Fundamental Law, he had no authority to actually implement his views on the country’s domestic and foreign policies. His excessive parliamentarism and constitutionalism would now and then impede the decision-making process. But Petrushevych’s political culture, parliamentary experience, and personal tactful attitude had an impact on the course of political events. Under his guidance, the UNRada acted as a real parliament in which the atmosphere of democracy and freedom of speech dominated.

In its three sessions in Stanislav (Jan. 2-4, Feb. 4-5, March 15-April 15, 1919) the UNRada worked on a number of bills that were urgently needed, ones that regulated Ukraine’s sociopolitical and economic life, laid its legal foundations, and met the aspirations of the masses. Thanks to this circumstance sharp social conflicts were successfully avoided. In contrast with Naddniprianshchyna and Bolshevik Russia, the ZUNR left no room for anarchy, otamanshchyna (local leaders’ arbitrary rule), or other phenomena that pose danger for newly established states.

Petrushevych supported the signing of the Polish-Ukrainian agreement on bilateral sanitary efforts, POW and internee exchange (Feb. 2, 1919). Pursuant to this agreement, 1,149 Polish inmates were released from internment camps — most of them cripples, women, children, men aged over 50, and parish priests. The Ukrainian side insisted on the quickest possible release of the Ukrainian inmates from the Polish camps (in Lviv, Baranow, and Dabie).

Petrushevych did not mind the activities of Polish civic organizations that remained loyal to the government, like the Polish National Committee and Polish Railroad Workers’ Committee in Stanislav. He facilitated the publication of Polish newspapers and trilingual ads. He was happy that the Jews officially took a neutral stand during the Polish-Ukrainian conflict and that they were increasingly favoring the Ukrainian side after the pogrom in Lviv on Nov. 22, 1918. At the beginning of 1919, they even manned the Galician Army’s Jewish Company.

DISCORD AS THE CAUSE OF FIASCO

In May-June 1919, the Polish troops, assisted by the Entente Powers, seized most of Galicia, and Romanian troops seized Bukovyna and Pokuttia. Threatened with a political crisis, the UNRada called an emergency meeting at the Basilians’ Monastery in Buchach on May 9 and vested dictatorial powers in Petrushevych: he was now both president and head of government. The functions previously fulfilled by the State Secretariat were now transferred to the authorized representatives (upovnovazheni). Thus, Holubovych was now the authorized person for internal affairs; Viktor Kurmanovych, for military affairs; and Stepan Vytvytsky, for foreign affairs.

Galician society largely approved of this decision, but the UNR leadership regarded it as undemocratic and perceived separatist trends behind it. Petrushevysh was then ousted from the Directory. In order to retain control over the region, the UNR government established the Ministry of Galicia headed by the Socialist Semen Vityk on July 4.

As a result, the relations between Petrushevych and Petliura deteriorated. There was even a (futile) attempt to arrest the Dictator with the help of I. Siiak, commanding officer of a detached railroad company (later he was a diplomat of the Ukrainian SSR in Warsaw).

The Soviet Ukrainian government tried to take advantage of the situation. Khrystian Rakovsky, who headed it at the time, offered Petrushevych to form a military alliance against Poland, with the sole condition that he sever contact with the Directory. However, Petrushevych’s interest in united Ukraine eventually prevailed. After the failure of a military operation at Chortkiv, toward the end of June 1919, he accepted Petliura’s proposal to the Galician army to the UNR Armed Forces in order fight the Bolsheviks jointly.

General Mykola Kapustiansky, who took part in the talks with the Dictator [Petrushevych], noted later: “We were all very much impressed by Dr. Yevhen Petrushevych. His was a big, dignified figure and his face was thoughtful. His firm, well-developed chin and the proud look in his eyes were proof of strong willpower. He treated every matter with the utmost care. One could sense that this man was fully aware of the burden of responsibility he was shouldering.” On July 16-17, 1919, Galician government structures and brigades crossed the Zbruch and deployed in the vicinity of Kamianets.

Despite the resistance of some of the Galician officers, Petrushevych supported the idea of having a joint command of both armies in the form of the Chief Otaman Headquarters headed by General Mykola Yunakiv. In the second half of August 1919, the united army commenced combat operations in Left-Bank Ukraine and briefly liberated Vinnytsia, Zhytomyr, and Kyiv, although Petrushevych had planned to seize the Black Sea coast (including Odesa) first, and then advance to Kyiv.

Starting with Sept. 24, the army was fighting on two fronts, against the Bolsheviks and Denikin’s troops. During the war, the UNR leadership held repeated separate talks with the Poles. Exhausted by a typhus epidemic, left without practically any boots to weather the autumnal drops in temperature, the only way to survive for the Galician Army was a truce, which its commanders signed with Denikin at the train station of Ziatkivtsi. On Nov. 7, Petrushevych learned the news and grew anxious. In fact, when he was shown the text of the Ziatkivtsi agreement at the Derazhnia station the next day, Petrushevych started crying. That same day, an angry Petrushevych fired Galician Army Commander Myron Tarnavsky and his Chief of Staff Colonel Alfred Schamanek for signing of the agreement with Anton Denikin’s Volunteer Army without Petrushevych’s approval.

The Chief Otaman demanded that Petrushevych have the dissenting general shot by a firing squad, but the Dictator resolved to have the case handled by court martial. The latter, presided over by Otaman S. Shukhevych, heard the case on Nov. 13-14, with Captain A. Shalynsky as the attorney, ruled that Tarnavsky’s actions, albeit unauthorized, were justifiable under the circumstances. The general got away with a demotion and was assigned command of the Second Corps.

Meanwhile, Petrushevych started receiving numerous accusations against himself: betraying the UNR, conspiring with the enemy, and sabotaging joint military operations. The situation was aggravated by the attempts of the Naddniprianshchyna government to force Petrushevych to surrender his post as commander in chief of the Galician Army in favor of Symon Petliura. Finally, on Nov. 12, a distraught Petrushevych adamantly refused to place the Galician brigades under the UNR Army HQ command.

That same day he called a meeting of the Galician government in Kamianets-Podilsky, inviting people who represented civic and political organizations, among them Directory member A. Makarenko and UNR War Minister Volodymyr Salsky. The latter confirmed to Petrushevych that the situation was hopeless: “The war is over for us. We’re defeated by typhus and not by the enemy’s military prowess. The Naddniprianska army can’t meet basic supply requirements; it can moutn no resistance [to the enemy]. The Galician army is in the same condition. It is mostly surrounded [by hostile forces].”

Under the circumstances some suggested that Petliura should be ousted from his office as commander, in view of his incompetence in the military field. Petrushevych took the floor in the end and what he had to say left the listeners speechless: “We must abandon our ideas of independence and seek a way out with Denikin. The Directory’s political course, the single-handed approach, is a risky path. Russia is not as frightful as Poland. We must agree to an autonomy because we are not mature enough for independence. The Ukrainians lack education and culture to build their own state, so discussing an independent Ukraine today is just fiction!” In other words, the Kamianets council was proof of the cardinal discrepancies between the Galician and Naddniprianshchyna leaderships on how to continue the war against the White Guard and on the prospects of the national liberation struggle. Petrushevych also realized that the Galician army, surrounded and unfit for action, had no alternative. Unless it refused to side with the White Guard, it would be captured.

On Nov. 14, Petliura made the last attempt to convince Petrushevych to surrender UGA command to the UNR, but Petrushevych refused to even discuss this sore issue. In the evening that day he was informed about Petliura’s arrangement for the Polish troops to occupy Kamianets. For him this was final proof of the Chief Otaman’s treachery.

He effectively allowed the Galician brigades to side with the armed forces of Southern Russia to wage a joint military campaign against the Bolsheviks. According to the new agreement (Nov. 17, 1919), the Galician Army retained administrative and organizational autonomy, the right to do official paperwork in Ukrainian; and the right to mobilize and reinforce its manpower by enlisting Galicians who reside in other countries. Petrushevych retained the authority to supervise and monitor what was happening inside the army. After Polish troops entered Kamianets (Nov. 14), Petrushevych left for Vienna through Romania. Meanwhile, the White Guard pledged to accommodate all ailing Galicians in their hospitals and they kept their word.

Needless to say, Galician riflemen’s switchover to their recent enemy could not but produce strong social reverberations. UNRada Vydil’s Social Democrat Semen Vityk condemned Petrushevych’s actions. In 1930, platoon commander Dmytro Paliev, Tarnavsky’s adjutant and a supporter of the alliance with the White Guard, stated: “This was a political blunder that shouldn’t have been made, even in the most critical periods.”

EXILE

As an emigre, Petrushevych campaigned for the restoration of the ZUNR. In November 1919, the Entente Powers presented to the Galician delegation in Paris a draft [agreement] that stipulated Galicia’s 35-year state autonomy within federative Poland. Petrushevych did not support it (although some Galician politicians, among them V. Paneiko, Ye. Levytsky, Holubovych, L. Levytsky, and Tsehelsky were prepared to accept the compromise).

Petrushevych felt hopeful about the treaty between the Entente Powers and Poland signed in Spa on July 10, 1920 because it allowed for the Curzon Line to be drawn in Galicia, which coincided with the ethnic Ukrainian-Polish borderline and would leave Eastern Galicia outside Poland. This treaty also provided for delegates from Western Ukraine to be invited to the future conference.

In August 1920, the government in exile was quickly reorganized. Now it boasted such experienced statesmen as Kost Levytsky, Volodymyr Sinhalevych, Stepan Vytvytsky, Yaroslav Selezinka, Osyp Nazaruk, and others. Above all, this government tried to prevent the League of Nations from adopting any legally binding decisions transferring Eastern Galicia to Poland. The head of the government dispatched Ukrainian missions to international negotiations in Riga and Geneva. Serious attention was being paid to relations with the United States. Petrushevych’s letters of protest were received by the Secretariat of the League of Nations, the Council of Ambassadors, and the President of the United States. Petrushevych did not rule out the possibility of allowing US concessions to come to the future Galician Republic.

In 1921, the League of Nations recognized Poland as a temporary invader of Eastern Galicia provided that the sovereign authority here belongs to the Entente Powers, and recommended the Council of Ambassadors representing the latter to consider the Ukrainian issue. In order to clearly define the aspirations of Ukrainian Galicians, Petrushevych’s government worked out and submitted to the allied countries a draft Constitution of the Independent Galician Republic. It was oriented toward Western democracies and provided for extensive rights and liberties for all ethnic groups.

At the same time, on the government’s initiative, the Polish parliamentary election and the conscription campaign were widely boycotted in Galicia. Finally, the Galician issue was placed on the agenda at the international conference in Genoa (April 1922). Petrushevych personally headed the Galician delegation which also included Levytsky, S. Rudnytsky, and Nazaruk. However, the discussion of Galicia’s future was thwarted. It was there in Genoa that Petrushevych first contacted representatives of Soviet Ukraine, specifically Rakovsky, who favored the confrontation between the ZUNR government and Petliura.

In the summer of 1922, Petrushevych held talks in Vienna with the Soviet [Ukrainian] diplomat Yurii Kotsiubynsky. The Bolsheviks aimed at splitting the Ukrainian-mostly anti-Soviet-emigre communities in Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Austria. Still supported by the Entente Powers, Warsaw launched an equally active diplomatic campaign to retain control over Eastern Galicia. In September 1922, its leaders took a series of measures intending to influence the international community. These included the passage of a bill on Galicia’s voivodeship autonomy, the foundation of a Ukrainian university in Lviv, and a statement inviting Petrushevych to launch negotiations.

On March 5, 1923, the ZUNR government sent a formal message to the Entente Powers with a draft solution to the Polish-Ukrainian conflict. The draft, however, envisaged that the full authority over Eastern Galicia would be transferred to the emigre government. It also said: “The Galician state will be ... the necessary and sole foundation for the consolidation of Great Ukraine.” However, the arguments presented by Petrushevych and his government in favor of creating something like “Eastern Switzerland” fell on deaf ears.

Nine days later, on March 14, 1923, in Paris the Council of Ambassadors went against the wishes of Ukrainians and passed a resolution annexing Eastern Galicia to Poland. The ZUNR leaders immediately filed protests to the Council of Ambassadors and the League of Nations. After publicizing these protests, in May 1923 Petrushevych disbanded the government in exile and closed diplomatic missions abroad. Galician statesmen and politicians returned to the region and engaged in legal activity. Petrushevych moved to Berlin where he continued to carry out diplomatic and propaganda campaigns, speaking in defense of his downtrodden people.

During his stay in Berlin, when he was bereft of moral support from his associates and found himself in financial hardship, Petrushevych succumbed to the illusion that the Soviet government had changed its nationality policy for the better, especially during the period of “Ukrainization.” He attended receptions at the Soviet embassy, met with Ambassador M. Krestinsky.

The Ukrainian Military Organization (UVO) was among the first ones to condemn his pro-Soviet attitude. The newspaper Ukrainskyi prapor (Ukrainian Banner) promptly responded with a series of articles criticizing the UVO. Soviet secret services tasked with monitoring emigre attitudes recorded in a 1923 memo: “Among the members of the ZUNR National Council are national democrats, radicals, and socialist democrats. The National Council is the ZUNR’s supreme government body. Its objective is to achieve independent for Eastern Galicia, which, in the opinion of the National Council, must serve as the foundation for ‘Great Ukraine.’ The ZUNR National Council has an executive body — or government — known as the Dictatorship headed by Petrushevych.

“There are constant discrepancies between the ZUNR Dictatorship and [Yevhen] Konovalets’ group, although both are dreaming of forming ‘Independent Great Ukraine.’ The main discrepancy between them is that the Dictatorship wants to gain independence first for Galicia, as the springboard for organizing all-Ukrainian forces and launching a struggle for united Ukraine.

“The Konovalets group believes that Ukrainians should acknowldge, for the time being, that Galicia is under Polish control. This will bring them amnesty from Poland and enable them to return to Galicia, join the ranks of military insurgent detachments, and penetrate Ukraine in order to create a Ukrainian state. Galicia’s independence should be considered only after this state is built... The Ambassadors’ decision should not be saddening or dispiriting; on the contrary, it should gear them up for combat... This is Petrushevych’s swan song, which is actually proof that he must have been led by the nose and otherwise deceived by various international swindlers... The time is coming for the Galicians to make their final choice of the path to follow — the Polish or the Soviet one?”

In 1925, a group of Petrushevych’s supporters led by O. Dumin split the UVO and formed the Western Ukrainian National Revolutionary Organization which fell apart shortly afterward. The pro-Soviet sentiments of Petrushevych and many of his fellow countrymen vanished in the early 1930s when Ukraine was swept under the tidal wave of GPU-NKVD repressions and terror. Petrushevych’s subsequent years as an emigre were grossly aggravated by financial problems.

Petrushevych died on Aug. 29, 1940, and was buried in the cemetery of St. Hedwig’s Cathedral in Berlin. The funeral arrangements, including the installation of the gravestone, were made by UNO people. In 2002, Petrushevych’s remains were transferred to the Lychakivsky Cemetery in Lviv and buried in the UGA soldier memorial.

Dr. Mykola LYTVYN, Ph.D. (History), heads the Research Center for Ukrainian-Polish Relations at the Ivan Krypiakevych Institute of Ukrainian Studies, the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine