“To Understand Ukrainians, You Have to See Ukraine...”

...through the eyes of Dmytro Klochko

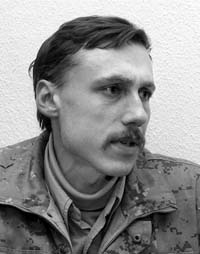

Dmytro KLOCHKO is a photographer, who specializes in portraits of Ukrainians and Ukraine. In search of the sites that he captures on film, he travels the country from east to west and north to south. Most of these sites are still little known or completely unknown to the public. Taras Kompanychenko, a professional kobzar and friend of The Day, arranged for Dmytro to meet with The Day’s editors, as he believes that Dmytro’s works are an organic extension of the newspaper’s column and book series entitled Ukrayina Incognita.

“Dmytro, what does photography mean to you? Would you tell us something about yourself?”

“I was born into a family of archeologists in Kyiv. As a child I traveled on various expeditions with my parents. In my adolescent years I discovered an interest in history. At that time I also took a fancy to photography. Early after enrolling at the journalism department of Taras Shevchenko National University, I understood that it was not my calling. For my diploma thesis I even selected a topic that had more to do with history. I never really practiced journalism. For me photography is a longtime hobby and profession. One of my main themes is Ukrainians and Ukraine, an extremely interesting and little-known country. Why stand in long lines in hopes of receiving a visa to travel, say, to Syria to see the Crusaders’ castles, if you can drive 200 miles outside of Kyiv and discover a marvelous work of architecture?

“I have visited many European countries: Italy, France, Switzerland, Lichtenstein, Croatia, Slovenia, the Czech Republic, etc. Comparing different nations and places is a thankless business. The whole world knows about Stonehenge in England, a circle of Druid stones. Researchers believe that it is a solar calendar. Yet we also have many impressive sites, such as megalithic structures, ancient stone sites. Recently, an expedition organized by a club of archeology lovers in Luhansk, headed by a retired school teacher, Volodymyr Paramonov, unearthed a megalith dating from the pre-Scythian period a short distance from Alchevsk, Luhansk oblast. According to one hypothesis, it was a temple or shrine, because metal and earthenware artifacts of the pre-Scythian and Scythian periods were unearthed nearby. With enough funding an archeological exploration of the site should begin this year. A similar site was discovered in Central Asia.

“Let me give you another example. The town of Oster, Chernihiv oblast, is home to the oldest Ukrainian monument dating from the Kyivan Rus’ period. This is the so-called St. George Chapel, which was built at the same time as the Church of the Tithes in Kyiv. Apparently, one part of the chapel collapsed into a nearby ravine, and the other part is neglected and in ruins. It is perched on the bank of the River Desna. The chapel was destroyed back in the 12th or 13th century, after which time it was never rebuilt, like St. Sophia’s Cathedral was. It is a piece of living 10th-11th-century history that you can touch. And it is a mere thirty kilometers outside of the capital. I felt a holy presence among these ruins.”

“Does it appear in guidebooks?”

“The chapel, of course, has architectural monument status, but no official plaque to confirm this. The St. George Chapel is featured in guidebooks on Chernihiv oblast, but I have never seen it mentioned in national guidebooks.”

“How long have you been making these photographic pilgrimages?”

“I have been traveling throughout Ukraine for a long time, but my professional trips with a camera began in 2002. I spent the whole of 2003 traveling, and made stops in Kyiv only to develop films. Last year my son was born, so I didn’t have a chance to visit any new places.

“I recall my first trip to Pereyaslav-Khmelnytsky in Kyiv oblast. I went there together with Taras Kompanychenko, who even gave a concert at a local music school. The town has 18 museums, but we decided not to visit them. More than anything, we wanted to see the old cemetery, which is 1,000 years old. Next to it is a 10th-century barrow. There I took an interesting photograph of four aligned grave crosses, two dating from the mid-19th century, one from the early 20th century, and the last one from the late 20th century, as though it belonged to a single family. According to locals, a Cossack judge is buried beneath the threshold of the local St. Michael’s Church.

“I was impressed by the patriarchal and archaic ambience of the town. It was early March, and people were burning beet tops in their vegetable gardens. The smoke had an unearthly smell. In the mornings, half of all Pereyaslav residents flock to the bazaar. Bazaars in raion centers are a unique phenomenon. My God, how they bargain there! It is nothing short of Gogol’s Fair at Sorochyntsi and Nechui-Levytsky’s Kaidash’s Family.

“To understand Ukrainians, you have to see Ukraine. Of course, stones have their own story to tell, but they also absorbed the spirit of those who built these edifices, laid siege to them, or betrayed, loved, and prayed in them.”

“Your thematic series “Ukrainian Families” and “Ukrainians” are reminiscent of postcards from the early 1900s series called the “Views and Characters of Little Russia.”

“In my opinion, this is a very successful stylization made to resemble this series. We produced these photographs especially for the folklore band Hurtopravtsi. Ethnographers have described the ancient clothing and dwellings of Ukrainians. But such houses are no longer built, while the few of them that have lasted to this day are rarely used as dwellings.

“Books offer different regional recipes, say, for borshch. I recently pondered the notion of Kyiv cuisine. After all, cuisine is also an element of national identity. The metropolis has always been multinational, and Kyiv cuisine is an interesting symbiosis of mostly Ukrainian and Jewish cuisines.

“I want to fathom all the mysteries of Ukrainian antiquity.

“Some of these photos were taken using prewar equipment. I collect ancient photographic equipment. Most of the items in my collection are in working condition, but I had to restore some of them. I bought them at Kyiv’s Sinny Market.”

“Why do you use monochrome film to capture such picturesque landscapes?”

“In my view, black and white photographs are better suited for capturing time and going back in time. I also like the play of light and shadows, hues, shades, and halftones. What’s the use of color in a photograph of Cossack graves? The stone cross itself is very detailed in terms of graphics and texture. All the focus is on it. Behind it is silence, in which some will hear the howling of the wind or the neighing of a horse. Such historical reprieves from the bustle of life are needed from time to time. Color conveys the mood and state of nature. I used to be obsessed with black and white photographs.”

“How do locals treat their architectural monuments?”

“It depends on the location. In Kremenets in Ternopil oblast, for example, they treat them respectfully. Many foreigners come to see the town with all of its architectural finesse. Meanwhile, sites located off the beaten path and which are not included in guidebooks are worse off. Locals graze their cattle on these sites, and holiday-makers come there for picnics, drink alcohol, and leave behind litter.

“There was a time when Ukrainians knew how to protect their shrines. A woman from the village of Harbuzyn, Korsun-Shevchenkovo raion, Cherkasy oblast, once told me an anecdote about some members of the Young Communist League who came to burn down their old wooden church. This happened before World War II. The church warden drank them under the table, and they forgot why they had come; they remembered only on the third day, after their heads cleared. Before their second visit, the warden ordered the villagers to stockpile their wheat and rye in the church, since nobody would set fire to a church full of wheat. That’s how they protected their church. We also have to know and study our national methods of resistance.

“Old people in villages told me that wooden churches were hardest hit in 1962, in Nikita Khrushchev’s time. In those days these monuments were burned down en masse. To save their churches, people would often convert them into warehouses. What is happening to our historical memory now?

“Mind you, Kyiv is becoming less and less Ukrainian. This is neither good nor bad; it is merely homage to fashion. Likewise, Warsaw can be hardly called a Polish city. Its architecture and ambiance reminds me of North America, at least a part of it. In effect, all megalopolises are very much alike. There are colorful Ukrainian elements in the capital, but they have undergone major transformations. Meanwhile, you can feel the primeval and authentic spirit of the Kyivan Rus’ princes, Cossacks, Ukrainian noblemen, and aristocrats primarily in villages and small towns throughout Ukraine.”

“Where are you headed in the near future?”

“Most of the time it happens like this: I plan my destinations in advance, but en route I come across many interesting places and people. Once, when I was returning from Volyn, I came across an estate that belonged to the famous Tereshchenko clan, in the village of Tryhirya, Zhytomyr oblast. It was built in the modern style at the turn of the 20th century. The latest technology was used in its construction: mortar brickwork and stucco finish, which was of much better quality than what they produce now. The estate had a tower, which probably served as an observatory. The building was destroyed during the Second World War. I never had time to learn more about it. I will have to go there some time and tell The Day’s readers about it in more detail.”