Cloak and Dagger Fantasies

Vladyslav Yavorsky chose a markedly modest, almost clichО title for his personal exposition at the Lavra’s Koliory Gallery: Landscape, Portrait, Still Life. This is poor self-advertising, of course, and Boris Zakhoder once complained that Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was too unpretentious; why not title the book something like Alice in Fantasyville or Alice in Nonsenseland? Be it as it may, such a sober-minded and outwardly neutral title (after all, the exposition is made up of works representing precisely these genres) betrays a touch of innocent coquetry.

Landscape, Portrait, Still Life is a new exhibit, of course, as most works are on display for the first time, but future researchers of Yavorsky’s heritage will have a hard time sorting out the dates, because every exposition unites works dating from different periods, from the earliest to the latest. In fact he regards the current show as belonging to a period long since past. The artist has never been the way he is now; his Koliory appearance is that of a romantic.

After graduating from Kyiv University he took up biology, but ended up an artist, painting glimmering magic, even scary but always captivating cityscapes. Most often they are not just empty but lifeless, at times crossed by rushing human shadows with dogs (as a special subgroup of the local fauna) or just dogs and demoniac cats (some of them are included in the current display, such as A Gloomy Morning and A Lonely Tree). Then there was the still life phase. His were mostly expressive (also present at Koliory), followed by biblical themes, executed with jeweler’s precision and unexpected sincerity.

Romantic?

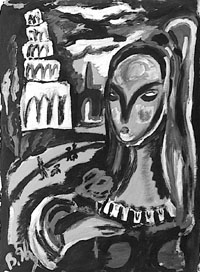

His fantasies have a boyish touch, subtly reminiscent of books we all read years ago, as in his

Hidalgo, Lady with Flowers... (the Leaning Tower in the background is not all that important), Don Quixote (obviously), Man Wearing a Fan (almost from Treasure Island), and Three Men in Top Hats (Dickens, of course). But there are different cases when the character is immediately recognized, but the subject- matter remains obscure: a high- handed scoundrel but with a pair of helpless eyes (Man with a Medal), a charming female captive, fragile yet courageous (Portrait of a Woman), a proud lonely Amazon (Lady with a Fan). At times this extravagant romantic seems to ridicule himself, and his sudden cloak-and-dagger fantasies (Bluebeard) or, in a desperate rather than brave gesture, turns his romantic dream into a cheap market show farce (Harlequin after the Show).