Hans BOLAND: “It was Russia that was born out of Ukraine, and not the other way around”

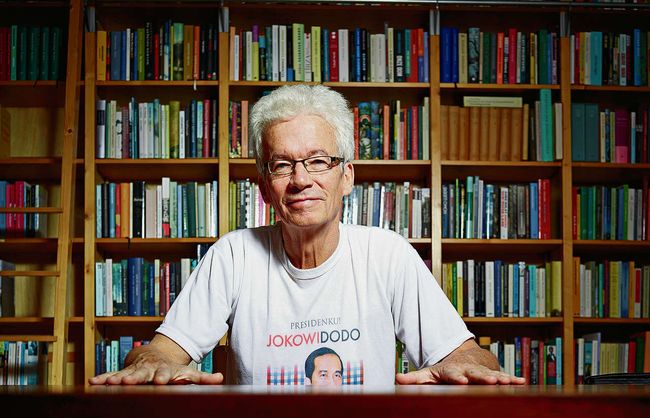

The Dutch translator who knows Shevchenko’s Testament by heart, shares about his love for Pushkin, revulsion towards Putin, and demythologization of the “Russian soul”

Russian literature, and Pushkin first and foremost, fills Hans Boland’s whole life. The well-known Dutch translator, Slavic linguist, and writer has translated almost all lyrical works by the “main Russian poet.” Moreover, he has acquainted the Dutch reader with Akhmatova and has worked with the texts by Dostoevsky, Lermontov, Mandelshtam, Nabokov, Shalamov, and many others.

However, the professional interests have not biased his civil stand and his set of values. In August 2014, when Boland was honored with an invitation to the Kremlin, to receive the Pushkin Award from the hands of Russia’s president, he refused the medal without hesitations. “I would receive such an honor with the greatest possible gratitude were it not for your president, whose behavior and way of thinking I despise and hate,” wrote the Dutch translator in his letter to the cultural attache at the Russian Embassy. “He represents a very great danger to freedom and peace on our planet. May God grant that his ‘ideals’ meet with swift and total destruction. Any relationship between him and me, between his name and Pushkin’s, is disgusting and unbearable to me.”

At the 22nd Publishers’ Forum in Lviv, Hans Boland will present the Ukrainian translation of his autobiographical book My Russian Soul, printed by Zhupansky Publishers. On the eve of the event, the famous translator gave an exclusive interview to Route No. 1.

After your refusal to accept the Pushkin medal from Putin’s hands, Russian media dragged your name through the mud. As far as I know, you even considered taking legal action. Did anything come out of it? How did the conflict with the Kremlin regime affect your perception of Russian literature?

“It is always hard for an ordinary man to fight the lawlessness of the state. It is hard in a democratic country, but even more so when a state is based on lawlessness, when lawlessness is its main driving force. Such things are even more disgusting when it comes to Russia, because the mixture of loutishness and cowardice, typical of Putin and his associates, traditionally urges them to avoid an open battlefield. Their instinct is to respond with meanness to an act of decency. Putin has always remained a miserable petty spy, molded by the USSR. It is this pettishness that differs him from his inspirer, Stalin (and even from Hitler). You might wonder who would care to fight such a worm? Personally I am ready to fight the evil, of which Putin is one of the most eminent representatives. Because of my love for Pushkin, Akhmatova, and others. Authority is temporary, while poetry is eternal.”

“I WANT THE UKRAINIAN READER TO FEEL THAT HIS COUNTRY IS FOLLOWING THE RIGHT PATH”

There has appeared a certain tendency in the West to draw a line between the attitude to Russian authorities and to Russian cultural heritage. Russian culture has traditionally been pictured as opposing the regime. Is this approach justified, in your opinion? How do you account for the fact that most artists in today’s Russia support the Kremlin’s aggression against Ukraine?

“And Pushkin, in his time, supported aggression against Poland! I will adduce only two examples, I think they will be quite opportune here. Take two contemporaries, Dostoevsky and Dickens, both great writers. And compare the desperate, desolate, almost inhuman state of mind in almost all characters of the former author with the light, loving, humane spirit of the latter’s positive figures. Whereas Dostoevsky hardly has any likeable characters to offer, Dickens has a crowd of them. And mind you, both authors’ novels feature people with huge problems in their lives.

“Another example: Tolstoy and Multatuli [a Dutch writer, whose real name was Eduard Douwes Dekker, 1820-87. – Author]. They are also both great writers and contemporaries. Multatuli has earned a place in eternity with his prophetic exposures of Dutch colonialism. Meanwhile, Russian colonialism (probably the only one still flourishing in our day) never sparkled resentment in Count Tolstoy, or any other Russian writer. Multatuli writes about women with respect, with deep belief in the equality of sexes, while Tolstoy describes the wretched, useless, boring, and sinful existence of Anna K.! I realize that it is not quite the answer to your question, but I hope that these two examples will help ponder over it.”

At the Publishers’ Forum you will present the Ukrainian translation of your book, My Russian Soul. What makes it valuable for you personally? Were any other of your works translated into Ukrainian before?

“In My Russian Soul (the title is an irony!) I described my 35-year-long relationship with Russia (the book was published in 2005), starting with the study of Slavic languages at the University of Amsterdam during the Cold War until my 6-year-long stay in St. Petersburg as the associate professor of Dutch in Yeltsin’s wild times. A trip across Putin’s Russia concludes the autobiographical part of the book. The core theme is the demythologization of the commonplace term, ‘the Russian soul.’ In a sense, it is also an attempt at ultimate judgment of the most important part of my own life. This is the first translation of my book ever, and I am proud of it particularly because it appeared at such a pivotal and tragic moment. I really want the Ukrainian reader to feel that his country is following the right path, the path leading from oppression and darkness to freedom and light.”

“THE RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN UKRAINE, LIKE NO OTHER TWISTS AND TURNS OF HISTORY IN THE PAST, OPENED THE DUTCH EYES TO THE ESSENCE OF THE RUSSIAN NATION”

In one of your interviews, you mentioned a visit to Kyiv in the 1970s. Did your personal or career path ever bring you to Ukraine after that?

“My first visit to Kyiv was in 1978. I wrote then that its atmosphere resembles rather the light-hearted Amsterdam than the gloomy Moscow. I remember the green chestnut trees, the imposing Maidan and Khreshchatyk and, of course, the magnificent Dnipro. I came back after Ukraine threw down the Soviet yoke. I have traveled across western Ukraine some five times. I have been to Crimea three times. I picked up some Ukrainian: a beautiful, rich, interesting language. I have read Shevchenko’s poems. An unmatched poet. I learned Testament by heart.”

French philosopher Philippe de Lara stated in an interview to The Day that Ukrainian culture in the West has been mostly ignored: it was either unknown, or considered as part of Russian culture. Do you agree with this opinion?

“Unfortunately. Until 1991, the Dutch hardly knew anything about Ukraine. Of course, one has to look for the causes in the notorious Russian messianism, the desire to rule the world and lead the mankind. Sometimes this desire rises to the level of psychic disorder. In Ukraine, it led to the oppression, often quite violent, of all things Ukrainian: the language and literature, the religion, the traditions. Catherine II and Stalin were probably the worst oppressors. It happened so that although it was Russia that was born out of Ukraine, and not the other way around, due to systematic distortion of historical facts to serve ideological needs (just consider the concept of ‘great Russia’) the entire world (alas, including Ukrainians themselves) grew to believe in this distorted picture of history and culture, believe in the ‘big brother.’ But Volodymyr the Great, Baptist of Rus’, Volodymyr Monomakh, and many other ‘founders of the Russian nation and culture’ were of Ukrainian, not Russian origin! And what about ‘the mother of all Russian cities’?

“These circumstances had two fatal effects: the unbearable arrogance of the ‘great brother/foe’ and the inferiority complex in the oppressed Ukrainian people. Fortunately, over the past years the Western mind has undergone great changes. Truth be said, so far they concern mostly political developments. Surprising as it is, but it is the recent developments in Ukraine that more than any other twists and turns of history in the past, opened the Dutch (and European) eyes to the essence of the Russian nation. We must be grateful for that. Now Ukrainians come to the Netherlands quite often, and it is great, because nothing arouses the most sincere interest like live communication does.”