Olena Honcharuk on decommunization...

Program “Cult or culture: development of participation practices in museums” is one of the most important events in the museum sphere this year

In the framework of this program, museum staffs from Kharkiv and Zaporizhia oblasts were trained to interact with visitors. These particular regions were chosen exactly due to their situation (close to the front) and the urgent need to speed up the processes of co-creation, gradually transforming the population from a passive electorate into active citizens. This program, realized by the Ukrainian Center for the Development of Museum Industry and sponsored by the Goethe-Institut, united top-notch experts from Germany, Finland, and Ukraine. Among them was Olena HONCHARUK, expert on PR and advertising, who has worked as PR coordinator for the National Art Museum of Ukraine (NAMU) for the past three years. We discussed the most successful exhibits at the NAMU of the recent years, the processes of decommunization, and the reasons for each and every museum to strive to become a star.

“THERE IS A CERTAIN HISTORICALLY DEVELOPED STEREOTYPE OF A MUSEUM AS A DEPOSITORY”

Any museum collection is something linked to our memory, be it personal memory or the one on the level of civil society and the nation. This memory could be someone else’s, or it can resonate with certain political or social developments. How can a museum become a resonator, what instruments one can find for this?

“I think this is something we will learn. Museums are good at collecting and preserving objects, and telling valuables from second-rate stuff. However, we still need to learn to work with memory. Before Maidan (I can judge about the time since I have been working at the museum) we did not pay a lot of attention to this. The NAMU implemented grandiose artistic projects, but now I realize that they could have produced more.

“When in February 2014 we came to work asking ourselves, ‘What to do?’, the first project with which the museum opened was the ‘Mezhyhiria Code’ – an exposition of artifacts which used to belong to Yanukovych. It was working live with things which were sinking into memory, it contained a crucial analytical moment, an attempt at reflecting society. Our major goal was to make the visitors see themselves in the exposition. And in that situation, the museum worked as a resonator: some resented us, the others, on the contrary, admired the powerful work, but at any rate we succeeded to move the public that never visits museums at all: the dwellers of dormitory suburbs, old ladies, and so on. At the same time, in front of the museum building, a project by French photographer Eric Bouvet, (R)Evolution, was opened. Bouvet photographed the events in downtown Kyiv in the winter of 2013-14 (he visited in late December, and a second time when the shooting started). That were two different series: one named ‘Kyiv’s Fatigue,’ with pictures of tired, exhausted people, and the other captured Maidan’s culmination. When people went to the museum to look at Yanukovych’s ‘treasures,’ they walked down an alley with those photographs displayed. From the very start, the viewers were inspired by the documentary photos. Curiously, before the closing of the exhibit someone cut the photos from the banners and took off the pictures hanging on the fence along Hrushevskoho Street. Perhaps this was done by those for whom the pictures were part of their personal history.

“The project ‘Heroes’ can be considered a kind of culmination. It was quite highly praised by international museum experts.”

I would like to touch upon this project in the context of decommunization, a painful process in our country. How do you think a museum should work with the artifacts dating from the Soviet time. Should their artistic value be emphasized or not?

“It seems to me that decommunization offers us a wealth of material, and a reason to talk. The museum’s mistake (or maybe a lack of competence) is that we are too slow to react to the messages from the outer world. After Maidan we were more dynamic, as we realized that a war was going on and we had to justify our routine, peacetime work. That was when the charitable project ‘Lions Do Not Abandon Their Kind,’ which allowed us to pull ourselves together, mobilize our resources, and offer emotional support to the troops and their kin and kith. The exhibit titled ‘Identity,’ held in the spring of 2016, also turned out to be topical. But on the whole, society offers challenges on a much more frequent basis. And this is when the museum must join in and have its say. At the National Art Museum not a single Lenin statue or portrait was destroyed. In our storerooms we have images of Stalin and other party functionaries. If a museum keeps this, it is its duty to get a message over to society: why it does not get rid of what is today considered outdated ideological rubbish.

“I would like to illustrate my thesis with the example of the monument to Cheka agents, the one which was dismantled on Lybidska Street. There was opinions split: some said that it was an interesting piece of sculpture and should not be destroyed, the others believed it was rubbish, and the more such rubbish a country has, the more brainwashed its people are. It seems to me that we should have used the situation and transformed this place, so it stopped being purely decorative. The monument has lost its symbolic nature, but it could have become didactic material. A museum (not necessarily the NAMU) could have entered public space and influence the decision as to making this place into, say, an alley of remembrance of the NKVD victims. So that a person could approach the monument feeling the absurdity of it: here is a monument to murderers, but it is very professionally executed.”

You formulated it very aptly: erasing the symbols of the communist epoch is like erasing memory. It is one thing when you reinterpret these things: they remain artifacts, yet you can work with this horrible past. And another, when you simply try to delete it and do as if it had never existed.

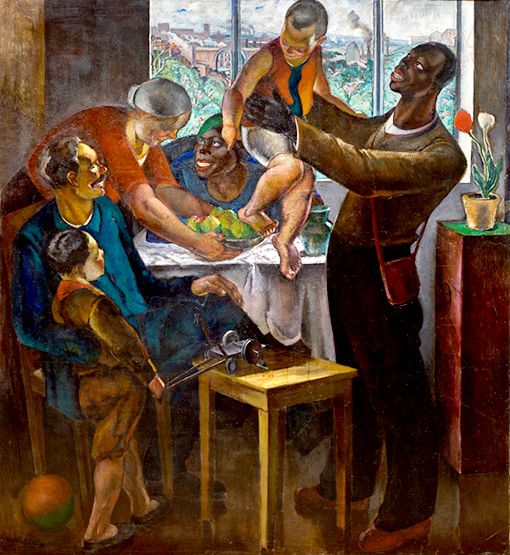

“In this respect, project ‘Spetsfond’ (special depository) is indicative. It comprises the artworks gathered in 1937-39 throughout the country – the works by too creative artists who painted ‘in the wrong way,’ contrary to the then official ideology. Fortunately, not all artists had to suffer, but they were forced to radically change their approaches to art. Some moved to other Soviet republics or abroad, some stopped painting, some took up teaching, but anyway, since 1937 their paintings were locked up in the museum’s store room. They saw daylight in the late 1970s, if I am not mistaken. After bans were lifted, research was done on those works. Miraculously, the special depository in Kyiv survived, while in Lviv such a depository was destroyed. And here is an interesting paradox: we are now looking at the paintings of the 1920s and 1930s and we realize that artists made a comeback there in the 1970s and 1980s. Tradition will survive anyway, it will grow through the modern forms of culture. So if there was a trauma, I support the idea of interpreting and embracing it. Otherwise, society will never be insured against a comeback of the past. Even if the commissaries will be wearing Ukrainian embroidered shirts instead of leather jackets.”

To me the museum’s prestige seems a very important moment. In order to discuss important issues with society, the museum must be a translator of ideas. How can prestige be built up?

“It is one of key questions, indeed. There is a certain historically developed stereotype of a museum as a depository, and that is where it is expert in, yet it is not seen as an idea-forming institution. For instance, the NAMU was created in the late 19th century in two steps. At first its creation was advocated by intellectuals, university professors, but at that time there was a lack of finances. Later it was also problematic until one of the mayors got interested in the issue, philanthropists joined in, and business owners supported the project (financially as well). And then the museum became an institution, a meeting place, a club. In the Soviet time it turned into an instrument serving the ideology. Back then, only those museums had a chance to remain interesting which had a good collection, or could afford decent expositions, like natural history museums. But today we see that even at those museums the exhibits wear out and gather dust, so even children are no longer interested.

THE SPETSFOND PROJECT THE NATIONAL ART MUSEUM OF UKRAINE DISPLAYED IN JANUARY 2014 TO APRIL 2015 COMPRISED THE ARTWORKS GATHERED IN 1937-39 THROUGHOUT THE COUNTRY – THE WORKS BY TOO CREATIVE ARTISTS WHO PAINTED “IN THE WRONG WAY,” CONTRARY TO THE THEN OFFICIAL IDEOLOGY

“Another question is, if a museum wants to influence, who will translate its views? No doubt that first and foremost this is the task of the museum staff. However, here we are not talking about emotional statements. It is consistent cooperation with the community, mass media, and educational and cultural establishments.”

“OVER THE RECENT THREE YEARS, OR EVEN FOUR OR FIVE, OUR VISITORS HAVE GROWN YOUNGER”

For a certain segment of society (and quite a considerable one) a museum is a sort of recreational vent. In music they speak of “philharmonic grandmas,” older ladies who visit all the concerts. There must also exist “museum grandmas.” Has the age composition of museum-goers changed over the recent years, or is there a stable nucleus?

“Over the recent three years, or even four or five, our visitors have grown younger, not in the least thanks to the efforts of the educational activities department which has launched various programs. For one, children’s birthday parties. No cake or juice is served, but children can play, do handiwork and quests. Our colleagues invent scenarios in such a way as to link them with collecting. There is a three-year program ‘Strategies of Visual Thinking’ which implants critical thinking so discouraged at school. At school there might be only two opinions, the teacher’s and the wrong one, and no one cares about what the child really thinks. Meanwhile here the moderator stimulates children to discuss, substantiate their opinion, and learn to listen to the others. Children-oriented programs allowed us to involve parents as well, who bring the kids aged three and older to us. In principle, this is a marketing approach. Lots of brands begin hooking their audiences while they are still very young.

“Another qualitative shift in the public happened when we started holding related events, such as concerts or book readings. Actors or performers attract their own audiences, and a part of them cling to the museum. Basically, I noticed that personality factor plays a great role in a museum. A lot of my acquaintances say, wow, since you came to work here, you breathed new life into the museum. I reply that it is only because I started writing about the museum’s events; it had been as interesting here even before me, but you did not notice it. If I am a convincing interlocutor and can engage people, or if someone finds me likeable, they will most likely transfer these feelings onto the institution, they will come and see.”

Another, very important moment concerning “sliding into pop-culture.” Is it something to be feared? Maybe the public who waited in queues to see the “Mezhyhiria,” will keep visiting other, not so much touted exhibits?

“It shouldn’t be feared, but it should be kept in mind. The risk is out there. We realize that we are forced to flirt with the public. But flirting can be done in a variety of ways. It is the question of your inner culture: how far will you go to get the visitor interested. You can hold an exhibit of fur coats, mantles, and jewelry in order to appeal to the visitor. But then a question arises: will it be a one-time favorite, or is the viewer going to ask for more? Too many ‘luna parks,’ and you will soon get a burn-out. The project ‘Lions Do Not Abandon Their Kind’ was a very useful experience, which helped rehabilitate in a complicated moral situation, but the formats and inner resources exhausted, and the work with the collection faded into the background…

“No doubt that some basic things, necessary for the creation of comfort, have nothing to do with ‘sliding into pop-culture.’ If a visitor can drink a glass of water or a cup of coffee, or sit and rest for a quarter of an hour, or thumb through some books, they could spend more time at the museum. If there is a room where children can do some fun activities, mothers could look at their favorite works.”

What do you think drives people to visit a museum?

“They seek to change the environment, to switch their thoughts over to other things. Or just follow the stereotype that ‘all cultured people do so.’ It is important for many to emphasize their status of cultured, worldly people who follow all the latest trends. Some museums are visited when people need to extend their knowledge on certain subjects. Or to spend time with friends or family. But in most cases I think they come just because it is interesting, or just for a kind of mental spa.”

What opportunities do Ukrainian museums (the NAMU in particular) have to advertise themselves? Where can that be broadcast?

“Besides our website and Facebook page, we normally send updates to various media and privately to individuals who leave their contacts in order to receive information. It seems to me that the city lacks a space where culture-bound organizations could promote themselves. Its appearance would be much-needed, for this would shape the city’s cultural image, people would get there information about various museums and their activities. Nowadays tourists are much more likely to go to the Jewelry Museum at the Lavra than to find the Lesia Ukrainka Museum. I think it would be wise to initiate a project to lend advertising space to museums and design a uniform bill. This would be a source of information, because direct advertising costs too much, museums cannot afford that without a partner. Meanwhile, it would be wiser to spend the proceeds from ticket sales in a more practical way: on educational programs or to create a comfort zone for the public.”

In our society, worth is measured only in terms of price. What those natural history museums must do which do not have a Mona Lisa in their collections? Is there an alternative to a price tag?

“There are in fact even virtual museums, which practically do not have any collections. I think there will always be a collection that might cost a lot in money equivalent, yet nothing is valued as high as live stories and the gift to tell them. The collections’ stories are just as unique as those of people. Our partners from the Ukraine Crisis Media Center are actively involved in supporting the museums in the east of Ukraine. They told about the museums of enterprises which produce tiles or some metal parts. Maybe, you can find millions of those parts worldwide, but these particular ones are precious because they are linked to the history of this place, to the histories of people. The histories of the people who created, collected, preserved, and studied the artifacts, make them one of a kind and give a voice to them.

“Any museum and its attractiveness could be assessed in a variety of practical criteria: the richness of the collection, the modernity of the exposition, high profile exhibits, well-thought navigation and viewer comfort, engaging guides and original formats, fun adverts and delicious coffee… Yet there is something elusive, unexplainable, and thrilling that attracts visitors to a museum. This is the magic that makes the hearts of both the visitor and the staff beat faster. This is the feeling of being part of a mystery, a presentiment of discovery, a forerunner of love. This magic is the key to success and progress of museums.”

Newspaper output №:

№73, (2016)Section

Culture