Crowned with imagination

May 11 marks the 110th birth anniversary of surrealism genius Salvador Dali

The life and destiny of the master, full of inevitable transformations, is duly reflected in his pictures and autobiographical books. In his 85 years, Salvador Dali worked his way up from a phobias-ridden, bashful, obstinate, and egoistic boy (the only son in the family of a Catalonian notary public) to a most scandalous artist who was even turned out of a left-wing society of his surrealist colleagues. The home stretch of this road was triumph of the true freedom of an acclaimed genius who found faith in God.

Salvador Dali was born in the town of Figueres, province Girona, Spain. He studied fine arts in a municipal drawing school and then at the Colegio de Hermanos Maristas. In 1921 he moved to a student hall of residence for gifted young people (Residencia de Estudiantes), where he met Luis Bunuel, Federico Garcia Lorca, and Pedro Garfias.

The young and eccentric Dali enthusiastically experiments with such vogue trends as Dadaism and cubism, but he is soon expelled from the academy for a cavalier attitude to instructors. Yet he continues to entertain his ideas: after meeting Pablo Picasso in Paris, Dali creates bold canvases that show influence of Picasso and Joan Miro. At the same time, he meticulously studies the works of Sigmund Freud – he employed the method of psychoanalysis in his later oeuvre.

In the late 1920s, the young Dali’s talent gains strength: he writes, in co-authorship with Luis Bunuel, the script of the surrealistic film Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog). Dali’s rich imagination and passion for profanation and scandal strikes roots in the Dadaist and surrealist milieu: he paints pictures that mirror his subconscious fears and dreams.

Andre Breton defined surrealism as “psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express – verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner – the actual functioning of thought in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.” However, Dali’s typical position of a solo leader is incompatible with the limitations that are natural in any artistic field and are indispensable for integrity of a specific group with its own manifesto. He scandalously abandons his friends and colleagues, stating categorically: “Surrealism, it’s me!”

Yet the very proximity to the milieu of surrealists laid the groundwork for Dali’s artistic future – he consistently developed this trend in all his lifetime, adding to this his own invention: paranoiac-critical method.

Dali also found his Muse – Gala (a.k.a. Gradiva – “the woman who walks”) – in a surrealist society, when she was the wife of poet Paul Eluard. He would begin to sign his pictures with her name, dedicate poems to her, and call all his experiments in her honor – from jewelries to fantastic cars – and finally, as an apotheosis of their long and hard way, he would present her with the beautiful castle Pubol.

During World War Two the Dali couple had to leave Spain – they first stayed in Europe and then, in 1941 to 1944, in the US. Here the Avida Dollars (“he who is after dollars,” as Andre Breton mockingly called him, misplacing the letters in his name) rapturously opened up the new horizons of his talents. He sells paintings to his aristocrat friends for handsome money, writes an autobiography, The Secret Life of Salvador Dali, and advertises his surrealistic vision of the world by way of provocative press reports. For example, The Times Herald which has a huge readership, publishes a sensational article, “One Day with Dali, or a Cow in the Library.”

As universality and businesslike spirit are quite in the American style, Salvador Dali receives various cooperation offers. He provides both the set design and the libretto for the ballet Labyrinth, and the Monte Carlo Russian Ballet stages it at New York’s Metropolitan Opera.

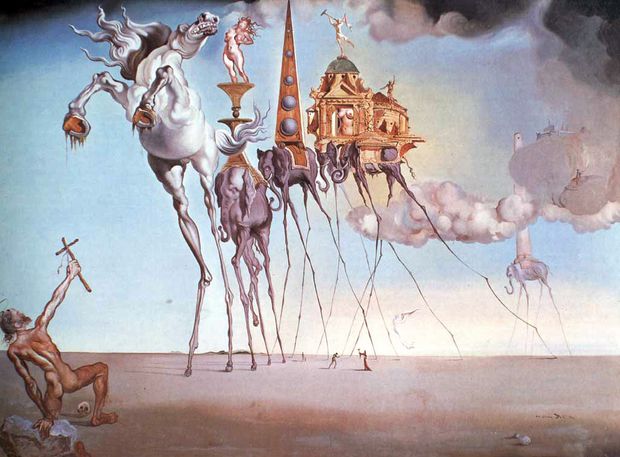

THE TEMPTATION OF SAINT ANTHONY, 1946

Together with Duke Verdura, Dali creates some stunning valuables inspired by “nostalgia for the Renaissance epoch.” He brilliantly plays on surrealistic figures in Vogue advertisements, makes astonishing shop window dummies, and creates, in cooperation with Elsa Schiaparelli, a particular beauty of madness in Shocking perfumes. Although being a few centuries away, William Shakespeare was also lucky to cooperate with Dali – in 1942 the artist makes set design sketches for the ballet Romeo and Juliet and paints a few easel pictures on this subject.

In the mid- and late-1940s Dali gets back to the legacy of old masters, and his painting technique noticeably changes. He studies the paintings of Renaissance titans and gives preference to the genius of Jan Vermeer and Jean-Francois Millet. In those years, Dali created the pictures Leda Atomica and the initial version of The Madonna of Port Lligat, the masterpieces that strike one with their inner silence and grandeur and are full of compositional austerity and the beautiful nobility of color.

Dali often turned to the subject of faith, creating Nuclear Cross and Corpus Hypercubus with a crucified Christ, the mural Last Supper after a fresco by Leonardo da Vinci. Experimenting with materials in book graphics, Dali executed watercolor illustrations for Dante’s superb Divine Comedy published in 1960-61 by George Foret.

The indefatigable Spaniard also enthused about science, particularly quantum physics and cybernetics, invented the Dalimobile, showed interest in binocular vision and the possibility of painting separate, almost identical, pictures (for the spectator’s right and left eye). A good orator, he willingly shared his innermost feelings with audiences, claiming that nothing was more sublime for him than the human DNA. Dali instilled his ideas in well-grounded research treatises and published Ten Recipes for Immortality in 1973.

The pictures of Salvador Dali who was called upon, in his own opinion, “to save painting from vandalism,” keep drawing grateful audiences not only in Europe and the US, but also in Japan.

Worldwide painting art, cinema and literature, the art of jewelry and design, were enriched with the discoveries of Dali’s genius, for he could see what others did not want to. Letting his imagination run wild and playing, he invented such things as “rainy taxi,” “lips sofa,” “lobster telephone,” a throbbing mechanical heart made of genuine rubies, and sliding cabinets in an erotically-attractive torso of Ancient Roman Venus. Breaking unceremoniously the stereotypes of thinking and the inveterate academic standards, the Spanish master created a world in which rapid-eye dreams and secret desires, fantasy and imagination occupied the most honorable place. He tried to achieve perfection in everything he was doing and rewarded his ancestors with masterpieces that remain topical as before even a hundred years on.

The Spanish master’s grandiose heritage has survived to this day mainly thanks to the Gala-Salvador Dali Foundation established in 1983 as well as private collectors and big museums all over the world. It is also possible today to plunge into the capricious and fantastic atmosphere, which the Great Surrealist personally created, by visiting his house-museum in Port Lligat or the theater-museum in Figueres. Also noteworthy is the Gala Castle in Pubol, where Salvador Dali spent his last years.

Olena Shapiro is an art historian