Two stories

Story one. The schoolteacher

The Day’s editorial team appreciates the fact that some important and interesting stories come from our readers. Though sometimes lacking in rigor, these stories are captivating because they are sincere. Our list of amateur contributors includes Serhii Hlushchenko (Zaporizhia), Tamara Orlova (Odesa), Mikhail Falagashvili (Irpin), and Myroslava Burlieieva (Vinnytsia), to mention but a few. The two-volume Extrakt 150 and Extrakt +200 of Den/The Day’s Library Series have chapters entitled “Den’s Mailbag,” that stress the fact that Ukraine’s latter-day history is being written by journalists as well as readers who contribute their impressions, emotions, and thoughts.

Not so long ago, The Day received a very interesting letter from Oleh Matiiuk, an engineer in Mykolaiv. This letter contains stories about several extraordinary individuals. Below are two of his stories.

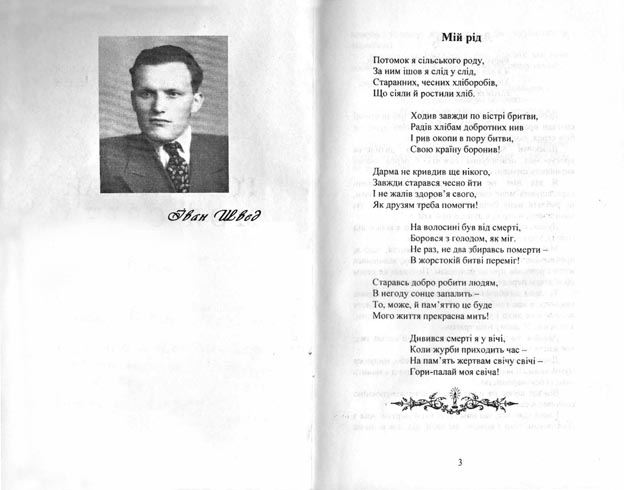

Pnivne is a village in Volyn. One of its residents is a retired schoolteacher by the name of Ivan Shved, currently 87. He is held in esteem in the raion and oblast. I can only thank God for having studied at a school whose principal — and Ukrainian teacher — was this man, a WW II veteran (who volunteered to join the [Soviet] Army and fought all the way from Korsun-Shevchenkivsky to Prague). He was born in Vinnytsia oblast, graduated from a local seven-grade school (with honors), then from a teacher training college in Berdychiv (cum laude) “to the accompaniment of Luftwaffe air raids”; ditto Berdychiv and Zhytomyr pedagogic institutes (1947-50 and 1950-53, respectively). He was a correspondence student at Moscow’s Institute of Foreign Languages (1948-50), but was barred access to exams because he wasn’t a member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The same happened with Moscow’s Institute of Literature.

Ivan Shved survived the 1946-47 famine by landing a job in Volyn, in 1946, among the thousands who migrated to the west of Ukraine in search of a living. At the time, Donbas mines used timbering from the Carpathian and Volyn forests. I have a photo of my grandfather, then a forest ranger, standing by a Studebaker truck loaded with timber. I was a kid, on my way to visit relatives in Stepove, a village not far from Mykolaiv, when I heard the wagon driver tell about his family having survived the famine by catching and cooking ground squirrels. Viktor Spytsia, a good friend of mine, a co-founder of the Ukrainian Language Society of Mykolaiv, told me, bitterly, that in the winter of 1947, the pigs at a collective farm, at the village of Bohdanivka, had been supplied makukha — press/oil cake — and that he had asked the farm manager to let him have a handful, to make his ailing mother happy. The manager had rudely refused. Spytsia had sent a story about this to a local newspaper later, but it was never published.

Ivan Shved was the principal of Pnivne’s grade school for more than 21 years, since 1948. He was fired one year after I graduated, because he wasn’t a party member. I still vividly remember the way he taught Ukrainian, his unconventional approach. He would give us unexpected, interesting assignments. Once he showed the class a picture of a bedridden, mortally-ill Ivan Franko and told us to describe what we saw in writing. Later he said my composition was the best. I still treasure the memory. He gave us compound Ukrainian sentences to analyze that were real brainteasers. He made us think things over, he instilled in us a love of Ukraine, its literature, language, and culture. He encouraged us to take up sports, dancing, music, explore exhibits — you name it. In 1964, marking Taras Shevchenko’s jubilee, we each received metal badges with an image of the poet and a line from his verse (I still remember it). The Shveds would turn every New Year’s Eve into a fairy tale for us at their place. His twin sons, Volodymyr and Ihor, my schoolmates, would often play their button accordions at the village club, including Oginski’s Farewell to Fatherland. This melody has since remained one of my favorites. I believe that our school’s teaching staff was formed at the time not only as assigned [by the local education department. — Ed.], but also as selected by the principal. They were good teachers who helped us find our bearings on the vast expanses of life.

I re-discovered Shved as a great teacher during a reunion marking the school’s 140th anniversary in 2003. We, former graduates, were addressed in refined Ukrainian by a man we had long known as a close friend. After that I corresponded with him. Among other things he sent a parcel with the book Keep Burning, My Candle (Kamin-Kashyrsky, 2008). In my opinion, this book ranks with Ukraine’s greatest publications.

It reads: “This comes from my soul tortured by a lasting pain. I vividly remember my barefooted childhood and all those hair-raising famine scenes. I’m haunted by these memories; they make me toss and turn in bed. The Lord must have allowed me to live this long, after surviving the living hell of the Holodomor, to relate the story to the descendants…”

His poems are a mirror reflection of Ukraine’s tragic lot. Reading his Poetic Reminiscences of the Holodomor, one is outraged by current realities, by the cold-bloodied cynicism, indifferent, scornful attitude, and outright incompetence of those in power, by their refusal to recognize the Holodomor as an act of genocide against the Ukrainian people.

I am enclosing herewith several Shved’s poems. He is the one to speak the truth about horrendous periods. His poetic insight is unique, for it reflects the tragedy Ukraine has sustained. And there is this painfully piercing footnote: “This publication has appeared in print at the author’s expense.”

My mother, also a schoolteacher and born in Vinnytsia oblast, survived two Holodomor famines. In 1945, she was sent to teach at a school in Volyn. She told me later about the trip: in a boxcar, all their ID papers impounded for the duration of the trip, forbidden to leave the boxcar. She vividly remembered the death of her brother’s family in 1932-33; as a child, she was horrified for life to watch her uncle’s wife commit acts of cannibalism — the woman was starving to death and knew not what she was doing. In 1946-47, she saved her mother and two sisters from death by starvation when she had them sent from Mykolaiv oblast to Vorokomle, a village in Volyn where she was working.

Ivan Shved’s poetic reminiscences urge the living to honor the memory of all those innocent victims of the Holodomor: “All we can do now, /To vent our feelings at heart, /Is to light a wax candle, /Keep it burning, /Sharing its tears with us…”

In early October 2010, I visited the home village to attend the wedding of my relative’s daughter. Lots of guests, festively laid tables, video cameras, a local rock band, the hard-working parents on both sides, happy and fatigued by preparations, the bride’s four younger brothers…

Each such visit charges me with creative inspiration, for on each such occasion I meet with relatives, former schoolmates; I see the autumnal forest with its fragrance of mushrooms, the old pond; I can smell the apples from what used to be my father’s little orchard… I visited my teacher, Ivan Shved. He was still in his small home, with his wife Halyna. Once again I enjoyed their delicious homemade dishes, along with Ivan’s strong 40-year-old herbal liqueur.

Ivan Shved also paid for the publication of his book In Merry Orbit (Kamin-Kashyrsky, 2009), dedicated to his long-suffering mother Viktoria Voloshyn.

The following lines from his poem “Parliament Fights” sound rather topical: “The courts of law, all statutes keep mum, / So does the Constitution; /None heed the people’s moans; /None want to hear them…/Law and truth are absent, / For want of people with any brains. / Who will be there to teach us reason? / Ukraine is sinking, overcome by grief, / With no one smart enough to save this ship. / Will there be a Washington to save her? / Or shall we have to follow in Moscow’s well-trodden step?”

His bitter-sweet verse about past Soviet and current realities in the Ukrainian countryside. Shved has another book ready for publication, but he isn’t sure about the project. Personally I can sign under every word in his poem My Birthday’s Toast: “People say you live just once; /I hear them, I’m living once…”

I wish him and his wife a hundred years, so they can keep their children, grandchildren, and former students happy…

Summing all this up — perhaps overstating it — my impression is that the younger generation tends to show a simplified attitude to the past, overlooking a number of grim aspects, including ignorance, the destruction of national traditions. Our young people appear indifferent about the language of instruction, with Ukrainian being officially substituted by Russian; about monuments to Russian tyrants being erected in Ukraine, including the statue of Joseph Stalin, that “leader of all peoples,” in Zaporizhia, the man who ordered millions of Ukrainians, descendants of the glorious Cossacks, jailed and killed for the sake of that shining communist future.