The stormy day

The second Kamianets-Podilsky period in the life of Volodymyr Svidzinsky (1918-1925)

(Conclusion)

The second part of this article does not answer two questions. First, why did Volodymyr Svidzinsky stress that he was a Soviet civil servant? Similar documents from that historical period state that this was not necessary. Second, why did he have his daughter baptized in church, considering his status as a “Soviet civil servant”? The former may have been caused by his fear for his life, but this assumption is not borne out by the facts. After the fall of the Ukrainian National Republic, most students and lecturers had left Kamianets-Podilsky for Prague. The Svidzinskys stayed in Soviet Ukraine despite the events that were taking in the surrounding world.

Those events were anything but hope-inspiring. There could be no question of euphoria under the Soviet regime. All around famous and ordinary Ukrainians were starving, as evidenced by questionnaires filled out by university lecturers and associates during this period. The terror of the dictatorship of the proletariat had reigned since the early 1920s. These events are thrown into vivid relief in documents stored in the archival fonds of Kamianets-Podilsky University and the Kamianets-Podilsky City Militia, including the following document from a file entitled “Secret Correspondence on the Search for Various Persons” [the language of all original documents is Russian]:

Ukrainian SSR

District Extraordinary Commission

For Combating Counterrevolution, Speculation, Abuse of Office, and Banditry

Kamianets District Executive Committee

12/VII/ 1921

Top Secret

Attention: Chief of the City Militia

The Information and Statistics Department of the Kamianets District Extraordinary Commission hereby requests urgent measures with regard to the search for and detection of the following persons on charges of various criminal offences...

19. Vrublevsky, Georgii Petrovich, former county commissioner under Petliura and the Hetman, citizen of Nemirov, Bratslav district.

On the strength of Cheka District Subcommittee Memorandum No. 12689 dated June 24. Case card No. 4302.

21. Shilmanovich, former minister of education under Petliura; available sources indicate that he is working at a Soviet institution in Kamenets-Podolsky.

On the strength of Memorandum No. 4582, Chief of Special Border Guard Division No. 5, dated June 26. Case card.

Head of the District Cheka Department

Chief of the Information and Registration Division

Head of the Search Service

Of course, there is no way to establish whether Volodymyr Svidzinsky was personally acquainted with any of the abovementioned people and many others who perished in the tidal wave of terror during the first years of Soviet rule in Podillia, but he had to have known what happened to them; he could not have failed to see what was happening around him.

There are other documents in the secret correspondence file that testify to the nationwide scale of the hunt for enemies in the Soviet Union:

Ukrainian SSR All-Ukrainian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counterrevolution, Speculation, Abuse of Office, and Banditry [VUChK]

6 Mironositskaia Square, Kharkov,

1926 Attention: All district Cheka Departments, Crimean Regional Cheka Department, DTChK [Road and Transportation Cheka], Special District Border Guard Divisions, Criminal Investigation Divisions, with a copy to the VChK [All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counterrevolution and Sabotage].

The Operations Department of the VUChK, reporting about persons involved in various criminal offences, requests immediate measures for their search, arrest, and transfer to the interested institution, with due notification of the VUChK.

These events could not have been unremarked by the poet or left him unaffected. His post as archivist, which Svidzinsky obtained with the agreement of the research institutions without coordinating it with the VUChK, made his position in the new social situation uncertain. After all, the poet and his wife Zinaida came from clergymen’s families. Counter to the family tradition, their parents allowed them to choose their own path in life, as evidenced by documents in the archives “Podillia Religious Consistory,” particularly the file “Service Records of Clergymen and Church Employees of the Podillia Eparchy. 1912” with the following entry regarding the poet’s wife:

Register, Church of the Kamenets-Podolsky Prison Castle. Senior Priest Iosif Iulianovich Sulkovsky, 57.

Children: 1. Boris, b. April 30, 1881. Currently staff captain, 34th Sevrsky Infantry Regiment; continuing his military education at the Nikolaievskaia Imperial Military Academy of the General Staff. Married.

2. Vasilii, b. Feb. 5, 1883. Graduate of Kazan University. Married. Works in an excise department.

3. Yevgenii, b. Feb. 5, 1883. Teacher at a one-grade parish school in Miksha Kitaigorodskaia. Married.

4. Nikolai, b. April 29, 1890. Assistant land surveyor on a land planning commission.

5. Zinaida, b. April 25, 1885. Graduate of Higher Women’s Courses, Moscow. Teacher at a boys’ high school in Alishki, Tavria gubernia.

6. Vera, b. Aug. 24, 1887. Graduate of Mariinskaia Women’s Gymnasium.

The poet’s wife was an extraordinary individual. We have discovered documents confirming that at the age of 18 she was a teacher’s assistant at a women’s high school in Kamianets-Podilsky. None of Volodymyr’s brothers followed in their father’s footsteps. Considering Volodymyr and Zinaida’s parentage, we can, of course, imagine how they felt living in Kamianets-Podilsky in the early 1920s, with the world of their childhood and youth, a world of values that they understood, collapsing around them.

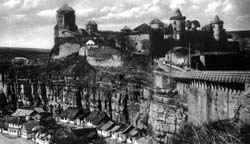

Documents from the archives of the Kamianets-Podilsky City Militia report on both human losses and the destruction of shrines of all religions without exception. Of course, the family was especially shocked by the destruction of the prison castle church in December 1921, in which Zinaida’s father had served as a priest for so many years.

In our opinion, Volodymyr and Zinaida remained in Ukraine because they wanted to — it was their conscious choice. The times were hard. In the early 1920s Podillia shared the grief and sufferings of the Ukrainian people. Did they accept the Soviet regime? Did they stand apart from social and historical events? One has to take into account the factor of real time; when people live amid stormy events they have a limited choice and are unable to withdraw from the course of events, even if they do not like them, and “switch seats” to a different and more comfortable one. People are destined to experience certain events, and Svidzinsky was no exception from the rule.

Since his birth Svidzinsky’s life had coincided with various global changes. His father was born in the age of serfdom. Orthodox clergymen were legally protected in tsarist Russia; their financial status fluctuated, but they were always free. But words about all people being equal, spoken from the pulpit, lost their meaning outside the church.

Then, starting in the 1860s, the peoples’ consciousness experienced an upheaval caused by the reforms in Russia. The peasants obtained their freedom and the right to own land. The process of mass land purchases in the western gubernias of Russia, including Podillia, began when the elder Svidzinsky brothers, Hryhorii, Volodymyr, and Vadym, were still young boys.

A year after Volodymyr stopped studying at the gymnasium an event took place that changed the surrounding world: the revolution of 1905. Its consequences for the Russian empire are generally known. Naturally, it had a profound impact on the mind of the 20-year-old young man. Then there was the 1917 revolution. Volodymyr was than 32. As a mature individual, he assessed it in the light of his own life experience. Volodymyr also witnessed three wars: the Russo-Japanese War, World War One, and the Civil War.

At this time, with the terrible life experience of the early 20th century behind him, Svidzinsky published a collection of poems entitled Lirychni poezii (Lyrical Verse, 1922). It was noticed by critics whose opinions ranged from approval to scolding. Was this Volodymyr Svidzinsky’s “optimistic tragedy”? The poet survived this trying period thanks to his wife. In fact, his creativity may be divided into two large periods: before and after her death.

Is it not worth examining his creative legacy as a reflection of the entire surrounding world? The difference between a genius and a hack is that the former reaches the summits of global generalizations while allowing the reader to find in his works motifs concordant with concrete events in the author’s life and ours.