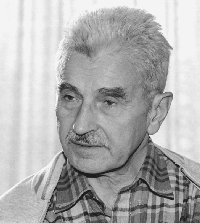

Diogenes in Twilight

"Like the Wandering Jew I am outside of time, building campfires of my memories," Yevhen Sverstiuk wrote already in exile. At a time when an anti-intellectual elite reigned everywhere this proud intellectual tried to return the world its original sense, defending age-old values. A cultural nonconformist, author of the rebellious essays "Ivan Kotliarevsky is Laughing" and "Cathedral in Scaffolding," his books, Shevchenko and Time, and his most recent, soon to be released, he cautions the contemporary against Pyrrhic victories and the pitfalls on the road to progress. He discusses the anthropological crisis, soberly pointing out that "the postcommunist world is going nowhere."

Yevhen Sverstiuk, however, can by no means be described as another professional Ukrainian mourner. Rather, he is a stoic. While championing Ukrainian spiritual rebirth, he treasures live personal religious feelings above all and denounces Pharisaic church ritual and pious spiritual mortification. In an isolated Ukrainian society where oligarchs seem determined to utilize not only the intelligentsia, but also any vigorous thought, Yevhen Sverstiuk, Ph.D. in philosophy, President of the Ukrainian Pen Club, and editor of the newspaper Nasha Vira (Our Faith), uphold the dignity of thought, emphasizing time and again that it is not worth trying to build another Tower of Babel, albeit this time a horizontal, virtual reality one. As did Taras Shevchenko, he would like to have The Word guard Ukraine. As an intellectual, he is convinced that poetry with its irrational insight is capable of dispersing the darkness of existentialism. He believes that true life is still ahead of us.

He is interesting with his ability to think, always a rare gift and especially now. Martin Heidegger wrote that thought soft-spoken, yet it leaves its distinct trace on the monolith of historical chaos and antithought. Now that the cultural symbol of our times is the "new Ukrainian" riding in his BMW with a loud horn, some say pessimistically that true thinkers again have to go hide in the catacombs, but not Sverstiuk. He will never hide anywhere, because he does not believe in man's solitude. "Suddenly the mob became visible and took the best places in society," wrote Jose Ortega y Gasset. How is one supposed to resist this process? Sverstiuk believes that the only way to retain one's ethnic individuality and remain true to one's moral principles.

"Sverstiuk does not use accidental sentences or unnecessary words. His style is concentrated energy of thought, reaching high aphoristic density," noted another man of the 1960s, Ivan Dziuba.

People visit Yevhen Sverstiuk from all over the world. One can meet him in New York, Paris, a village church somewhere in Volyn, or on the grounds of a former Soviet prison camp in Mordovia. He meets with the Pope, Vaclav Havel, Zbigniew Brzezinski, discusses Ukrainian literary news with George Shevelov and George Luckyj, and Russian literary life with Andrei Bitov.

His is a harmonious combination of innate aristocratic courteousness and deeply rooted democratic approach to people, because he sincerely loves his neighbor without making a big deal of it.

A priest is asked in one of Camus's books: "Don't you think that the efforts you make during the day vanish in the end, that they are wasted?"

"Yes, I do," he replies, "That is why I start everything anew the following day." This fully applies to Yevhen Sverstiuk's current approach.

He was born in 1928 to a peasant family. "We had a home with a big orchard. It was our plot dating to my great grandparents. We grew our own grain and we even had a small forest, a blue spot on the horizon, always beckoning to me to set out I knew not where." In 1952, he graduated from the psychology section of the Department of Philosophy. In the General Pogrom of 1972, he was arrested the first time. The investigation established that a well-known samvydav work, "Ivan Kotliarevsky is Laughing" (the essay has retained its topicality, by the way), and others were "documents created and disseminated... for the purpose of undermining and weakening Soviet power." He received seven years in a hard labor camp in the vicinity of Perm (Russia) plus five years of exile in Buryatia. He became an honorary member of the International Pen Club in 1978. Ironically, that same year he received his last "diploma" at the prison camp: a certificate attesting to the bearer as a "stoker of steam boilers."

At seventy, writer Yevhen Sverstiuk remains true to his stoic and romantic

self. In this sense he is a time-traveler on a visit from the age of chivalry,

gothic castles, self-sacrifice, and heroism. His invincible figure towers

over the rotting deck of our rusty ship as it feebly struggles amid the

giant waves. The hull is giving way, the water gushing in through cracks

in the hold, the crew and passengers are panic-stricken. And only the gray-haired

captain remains as calm and polite as ever, firm in his belief that the

ship will weather the storm.

Newspaper output №:

№46, (1998)Section

Culture