Post-Yugoslavian space and terror of little differences

Miljenko JERGOVIC: “Croatian politicians will realize that the war is close only when a bomb hits their bed”

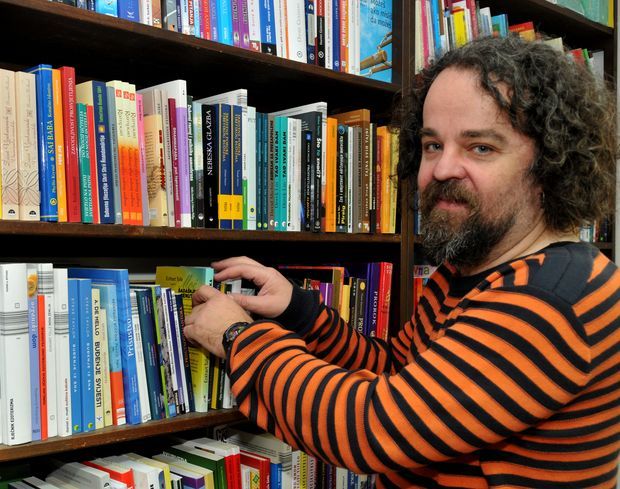

His texts have been translated into 20 languages, he is considered to be the most successful writer of Western Balkans. Last year he won the Angelus Central European Literature Award and literary critics predict that he will become a Nobel laureate. In his books Miljenko Jergovic describes the Balkan experience of war, “subtly operating everyday realities, which under his pen turn into powerful symbols” (from a book annotation). Poetess Kateryna Kalytko whose translations of Jergovic’s books were published in Ukraine says that Miljenko Jergovic’s main weapon is surgical humanism. “He is adored or hated, people start the day with his stories and cannot go to sleep, he describes the war in his native Bosnia in a penetrating way and prevents the national Croatian conscience from drowsing,” Kalytko writes. “He works equally subtly with collective memory and family history, equally impressively describes the estrangement and hostility, which breaks out from a tiny flash.”

Miljenko Jergovic authors five poetic collections (the first one was published back in 1988), six short stories, nine novels or stories, numerous essays and even a play. Translations of his books The Mansion in the Walnut, Inshallah Madonna Inshallah, Ruta Tannenbaum have been published in Poland and Belarus. In Ukraine, the ice was broken by Tempora Publishing House. In 2013 his Price o ljudima i zivotinjama/Sarajevski Marlboro+Macka covjek pas (Stories about People and Animals), a literary reflection dedicated to Balkan conflicts of the end of the 20th century and life after war translated by Kateryna Kalytko saw the light in Ukraine. This year the Ukrainian readers have an opportunity to read Srda Sings, in the Twilight, at Pentecost, for which Miljenko Jergovic has won the Angelus Award. Like the annotation reads, “This is a panorama of modern Zagreb; via the life of the main characters, intricately intertwined around the central plot, the author reveals the mentality and complexes of present-day Balkan country.”

Why are we speaking about Miljenko Jergovic as actually a Western Balkan author, not simply Bosnian or Croatian? The reason is that Miljenko Jergovic is a representative of both literatures. Born in Sarajevo, during the several-year Serbian siege in 1992-95 Miljenko Jergovic had to move to Zagreb, thus finding himself on both sides of the conflict. There are people who tell him to leave Croatia and not to “dirty the home nest,” dooming him to migration. How does the writer overcome this estrangement? Having met Miljenko Jergovic at the Forum of Publishers in Lviv, where he was invited as a special guest (it is worth adding that owing to the forum Miljenko Jergovic came to Ukraine for the first time), we had an opportunity to talk about double identity and how the war changes people.

Mr. Jergovic, Kateryna Kalytko calls you a man with two identities. How do you identify yourself?

“Identity is a complex thing that is changing on an everyday basis. For example, today I feel differently than seven days ago. So, my identity has changed over these seven days. But the fact is that I was born and grew up in Sarajevo, where mostly Serbs and Muslims live, and now I am residing in Zagreb, where the most of population are Croatians. And I was born in a Sarajevo Croatian family. Living in Zagreb, I feel more a Bosnian than when I live in Sarajevo where I mostly feel as a Croatian.”

In a preface to the book Srda… you write that people often tell you to leave Croatia. How do you overcome this estrangement?

“Yes. In Zagreb people whom I scarcely know tell me to get out of Bosnia. In a certain way I take this as a compliment. This means that I infuriate people whom I need to infuriate. In such a way I practically exposed fascists among ordinary citizens, because if a person says to someone in the street, ‘Go away!’ or ‘Go there!’ it means that this person is a fascist. On the other hand, it is even pleasant to feel as a foreigner in Sarajevo and Zagreb. I think that it is not bad to be a stranger everywhere.”

The religious and mental space of former Yugoslavia is very versatile. How is national cooperation built among these countries? How do they establish dialog?

“They either establish it, or not. Like it was before the war. The multinational regions that are living in such a conglomerate are interlaced by love and hatred. I take interest in common language areal. Because most of people from former Yugoslavia understand one another. Or, actually, speak the same language. This is what makes this region in a certain way unusual and interesting. And this is what sociologists call terror of small differences. This is hatred caused not by great differences, but namely by the lack of them.”

You have survived the war. How did it change you psychologically?

“Of course, the war has changed me. For me the time before the war and after it are two different lives. And I was the one who chose the way for the war to change me. After the end of the military actions I refused to live in the state of hostility to other people. For example, I still reject the idea that the Serbs should be considered enemies. I reject it out of many reasons. The main one is that I don’t want the fact of the war to change my personality, its structure, and my life. How has the war changed me? For example, whereas before the war if I met at one table with a radical nationalist who would say that all Serbs must be killed, I would consider him a fool. After the war I consider him my enemy. Now I see him as a person I must fight against. Previously I thought that such people cannot have any influence. Today I am much more interested in fascists who can be found among your own people, rather than fascists of other nationalities. You can fight only against your fascists. This is the main difference between war and peace. For peace usually lasts longer than the war, fascists from your own people are much more dangerous.

“In my opinion, literature where the writer chooses one side of the conflict cannot be literature. I take interest in individuals, their argumentation. I don’t take interest in collective things.”

In June this year in your column you emphasized that Ukraine cannot be far for Croatia and Croatian politicians in particular. In your opinion, have they realized that this war may touch everyone?

“Unfortunately, not. Croatian politicians will realize that the war is close only when a bomb hits their bed. Apart from that Croatian politicians are the silliest type of nationalists. They verbally support Ukrainians only because Serbs verbally support Russians. And what is good for Serbs is bad for Croatians. And vice versa. So, they don’t know anything about Ukraine and don’t want to know. This is terrible. The governmental policy of Croatia concerning Ukraine is a policy of the American State Department. Everything is decided for them by Obama and his government officials. If Obama likes Ukrainians as ‘good guys,’ it is good for Croatian politicians respectively. This is very insulting for me. Not only because Ukraine is very close to Croatia. Not only because part of Ukraine for 100 years has been a part of the same state as Croatia has been. As for me, the fact that Croatian politicians don’t find it necessary to think about such big and terrible thing as Putin’s policy concerning such a big European country as Ukraine is inadmissible. In such a way Croatia shows itself as a miserable American corporation. However, Serbian love to Russia has the same reasons, manifestations, and results. It is idiotic, only in some other way.”

The war in Ukraine and former Yugoslavia is often mistakenly compared. For there is no civil war in Ukraine, there is Russian invasion. What is your attitude to this? Do you think that post-Yugoslavian experience can teach Ukraine anything?

“In Yugoslavia the war was not purely civic, but there were signs of this. I basically don’t like the comparison of so different situations. People use such comparisons as a rule when they know nothing about the real state of affairs. But there is one thing which should be mentioned today. In 1992 the international community promised Bosnia and Herzegovina to protect it. And it did not fulfill its promise. In a similar way the international community, Europe and America are promising something to Ukraine. In fact they are waiting for what will go next, and hope that Putin’s appetite is not too big, they pin hopes at his reason. Like they used to pin hopes at Slobodan Milosevic’s reason. I think this is the only possible comparison.

“Today as a small private civil person whose opinion is absolutely unimportant on the scale of the planet, I can say openly that I support Ukraine, but not in the way the Croatian government does. Unlike them, I am in no way attracted to the American policy. I support Ukraine because it is decent and that’s how it should be. I think no one can seize anyone’s home land. Now the world badly needs human solidarity.”