<i>The Day</i> and the National Television Company of Ukraine present

We would remind our readers that the National Television Company of Ukraine has launched two projects commemorating the 20th anniversary of the Independence: “Twenty Years to the Dream” and “The Faces of Ukraine.” The short reels about the outstanding historical figures are developed on The Day’s pages. The project was opened by the insights into biographies of Kateryna Bilokur, Mykola Amosov and Oleksandr Dovzhenko (see The Day No.41). Today we suggest our readers recalling Hryhorii Skovoroda, Viacheslav Chornovil, Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny and Valerii Lobanovsky.

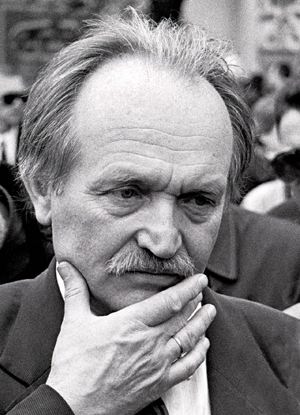

VIACHESLAV CHORNOVIL: “…I WOULD HAVE CHOSEN THE LIFE I HAVE LIVED”

“If you asked me if I regret about my life, about 15 years in prison, I would answer: not at all… If I had had to start from the very beginning and make choice, I would have chosen the life I have lived.” The evidence of the sincerity and firmness of these words were all the heroic deeds of the politician, writer of political essays and journalist Viacheslav Chornovil. He was born on December 24, 1937, in the village of Erkiv in Cherkasy oblast in a family of teachers. In 1960, he graduated from the department of journalism at the Shevchenko Kyiv State University. He worked on the television, radio and in the newspapers, particularly, in Moloda Hvardia.

In 1965, during the premiere of Sergei Parajanov’s film Tini Zabutykh Predkiv [Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors. – Ed.] at the Ukraina movie theater Ivan Dziuba, Vasyl Stus and Viacheslav Chornovil told the audience about the secret searches and arrests of the intellectuals in Ukraine and Moscow. The unrest in the cinema was liquidated by the KGB workers. In April 1966, during the trial of his confederates Horyn brothers in Lviv he took another courageous step: he refused to testify since the session was closed and therefore illegal. For this Chornovil was condemned to three months of forced labor.

The same year he edited the book called Gore ot Uma [Woe to Wit. – Ed.]. The author agreed to send the typescript abroad. He was given the International Journalism Award for this work but the Lviv Regional Court “awarded” him on its own: he was condemned to three years of prison for the anti-Soviet activity. In 1969, Chornovil was amnestied and released and started actively participating in the publication of the magazine Ukrainsky Visnyk. In January 1972, there was a new wave of dissidents’ arrests in Ukraine and Chornovil was in the prisoner’s box again. He endured six years in camps in Mordovia and Yakutia, three years of exile in Chappanda, the new accusation and the new sentence. Only in 1985 he came back to Ukraine where there was the period of perestroika. He resumed the publication of Ukrainsky Visnyk which shortly after acquired the status of the official press organ of the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union. The outstanding politician was one of those who created the political party Narodny Rukh Ukrainy [People’s Movement of Ukraine. – Ed.] in 1989 and headed it since December 1992.

In 1990-92, Chornovil headed the Lviv Regional Council and the Regional Executive Committee trying to carry on the democratic reforms in the oblast. In 1991, he became the MP and was a chairman in various Parliament committees and the fraction of the People’s Movement of Ukraine. During the presidential campaign of 1991, Chornovil ran for president as a representative of the People’s Movement of Ukraine. He took the second place then and received 23 percent of votes. On March 25, 1999, Viacheslav Chornovil tragically died in a car accident whose mysterious circumstances are still being investigated. For his selfless work for the independence of Ukraine and his fight for the rights and freedom of the Ukrainian people he was decorated with the Yaroslav Mudry Order and the Taras Shevchenko State Prize. In 2000, Chornovil was posthumously awarded the title “Hero of Ukraine” and the State Order.

HRYHORII SKOVORODA: “CRYSTAL-CLEAR CONSCIENCE”

“I was born poor to poor parents; I made my bed of poverty and covered myself with it.” These words exactly characterize the life of the most outstanding Ukrainian philosopher of the 18th century, enlightener, writer, teacher, musician and singer Hryhorii Skovoroda. He was born in December 1722, in the ‘sotnia’ town [town for billeting. – Ed.] of Chornukhy of Lubny regiment in a poor Cossack’s family.

When he was 16, Skovoroda entered the Kyiv Mohyla Academy where he studied poetry, philosophy, rhetoric, theology, learned the old and modern Greek languages, the Latin, German and Polish languages. In 1742-44 owing to his beautiful voice and musical abilities Skovoroda served in the St. Petersburg chapel royal. The commission headed by General Vyshnevsky was setting off for the Hungarian city of Tokay. The young man was included into the commission since he spoke foreign languages well, knew the clerical traditions and had musical abilities. Being abroad, Skovoroda had an opportunity to communicate with the scientists form Austria, Hungary and Slovakia.

When he came back to Ukraine Skovoroda taught poetry in the Pereiaslav Seminary.

In 1759-60, Skovoroda taught poetry at the Kharkiv College of Humanities yet he was fired because of his refusal to take monastic vows and later be ordained. Since then he stopped his teacher’s activity and service and travelled through Ukraine writing his first philosophic works. He definitely refused any offers of clerical or secular positions. Even Catherine II failed to attract him to the court. “I will not leave my homeland. I treasure my pipe and my sheep more that the tsar’s crown,” he proudly declared.

The philosopher protested against tsars, clerical and secular feudal lords. In his works Vsiakomu Horodu Nrav I Prava [Every Place Has Its Customs and Rights. – Ed.], Son [Dream. – Ed.], and Rozmova Piaty Podo-rozhnikh Pro Spravzhnie Shchastia [Conversation among Five Travelers Concerning Life’s True Happiness. – Ed.] he brightly depicted their parasitic way of life.

I know that the death

Is like a strong scythe,

It will not show mercy to even the tsar.

The death does not care

Whether it is a peasant or a tsar

It will devour everything

Just like fire devours a straw.

Who can ignore its horrible steel?

Only the one whose conscious

Is crystal-clear…

This “crystal-clear conscience” became the cornerstone of Skovoroda’s moral and ethic views, reflected in his theory of “similarity” or “similar labor.” It implies that people have to work using their inclinations to some kind of work. If everyone does so, the philosopher remarked, the society will work like a clock whose gears turn in different directions but provide its normal functioning.

Over 25 years and till his death he traveled through the left bank of Ukraine propagating his ideas. His clothes were very simple and he did not differ form other peasants at a glance. He did not eat meat or fish. He did not sleep more than four hours a day and woke up before the sunrise. He always travelled on foot if the weather allowed. He was always cheerful, restrained, happy with everything, eager to talk and respectful towards the people regardless of their status. He visited those who were ill, comforted those who were sad, shared the last with the poor, chose friends and loved them for their heart and was devout but not superstitious. He always had in his bag a luxurious Bible and a flute with the ivory mouthpiece.

Finally, the age and illnesses showed up and walking was getting more and more difficult. The philosopher found his last shelter in the village of Pan-Ivanivka near Kharkiv. He died there on November 9, 1794. According to his will, Skovoroda was buried at the cemetery on a high hill near the forest. The signature on his gravestone reads: “The world tried to catch me but failed.”

PETRO SAHAIDACHNY. ONE OF THE MOST OUTSTANDING EUROPEAN COMMANDERS

Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny was one of the greatest European commanders, a politician and diplomat.

The Hetman of the Ukrainian Register Cossacks was born in 1570 in the village of Kulchytsi in the Lviv region. He came from a family of the Orthodox Polish aristocrat who had his own coat of arms and studied at the school of the Lviv Community and at the famed Ostrih School.

In 1601, he arrived to the Zaporizhian Sich. He showed himself as a courageous and skillful warrior during the Cossacks’ campaigns to Moldova and Livonia and quickly gained the authority among the Cossacks. Led by Sahaidachny, the Cossacks carried out successful campaigns in Turkey and the Crimean Khanate.

Europe found out about the Ukrainian Cossacks’ valor after they had captured the Turkish fortress of Sinop in 1614 and later Kafa, large slave market in the Crimea. The Cossacks fought 14,000 Muslims, sank lots of Turkish galleys and released thousands of Ukrainian prisoners.

Sahaidachny realized the necessity to fight against Rzechpospolita [Poland. – Ed.] yet he acted as a diplomat seizing every opportunity to implement his ideas.

This is what happened in 1618 when the king of Rzechpospolita approached Hetman Sahaidachny asking him to participate in his campaign against Muscovy. He listened to the king and set up the following conditions: to expand the Cossacks’ territory, give freedom to Orthodoxy in Ukraine, increase the number of the Register Cossacks and acknowledge the judicial and administrative autonomy of Ukraine. The king and the Seim agreed with Sahaidachny’s requirements. The latter gathered the 20,000 army and in August 1618 started moving far inland of the Duchy of Muscovy through Sivershchyna. His Cossacks captured Putyvl, Rylsk, Kursk and Yelets, in general, over 20 cities in Muscovy, defeated the people’s volunteer corps headed by the dukes Pozharski and Volkonski and the regiments of Buturlin. In September, the Cossacks and the Poles besieged Moscow. Sahaidachny’s army stayed at the Arbat Gates of Zemlianoi Val and was preparing for the assault. However, the Polish gentry refused to continue the war and signed an advantageous armistice with the Muscovites.

In the Polish-Turkish war which started in 1620, the Sultan’s army defeated the Poles in Moldova and prepared for a campaign against Rzechpospolita. Sahaidachny and his 40,000 army succored it again. He played the leading role in defeating the Turkish army of 300,000 near Khotyn demonstrating the perfect skills in managing the infantry and cavalry and coordinating their actions attacking the superior enemy and defending from it. The Khotyn Peace signed by the Turkish and Poles was advantageous for Ukraine, too.

The Hetman also cared about the national education and culture development. He and the whole of the Cossacks’ Army entered the Kyiv Community and patronized it. Besides, Sahaidachny aspired to returning the importance of Kyiv as the orthodox and cultural center. He encouraged the activity of the Lavra metropolitan Yelysei Pletenetsky and the group of scientists, publishers and writers he had created at the printing house of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra. In 1620, owing to his authority, Sahaidachny made the Jerusalem Patriarch Theophan resume the Kyiv Metropolitanate.

The Khotyn battle was the last one for the Hetman. Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny died in Kyiv in April 1622 from numerous wounds received at the battleground. The Ukrainian people kept the memory about Sahaidachny in many Cossack’s ballads and songs. One of the Kyiv streets at Podil is named after Sahaidachny.

VALERII LOBANOVSKY. AHEAD OF HIS TIME

“In order to win one has to be ahead of his time” – this was not just the favorite phrase of the Ukrainian footballer and world-level coach Valerii Lobanovsky but the philosophy of his life.

Born on December 6, 1939, in Kyiv, he got interested in football since his childhood yet his hobby did not prevent him from finishing school with silver medal. Although he had a real possibility to play in Dynamo Kyiv football club, he entered the technical university.

People still tell legends about his “dead leaf,” the cut corner kicks that made the ball follow the unpredictable arc making a goal. Based on his own calculations he modeled and grounded the theory of these kicks from different places of the field, in particular, from standard positions and after systematic training made them his speciality. Since 1957, the young forward of Dynamo Kyiv quickly became renowned not only for his “dead leaf” but also for his high speed dribbling with the direction change. In 1960, the new favorite of the public became the best forward of the club scoring 13 goals. Lobanovsky played for Dynamo for six years and finished his career in Chornomorets Odesa and Shakhtar Donetsk. Playing in clubs, he won the silver at the 1960 national championship, became the champion of the USSR and the owner of the USSR Cup in 1964. Apart from his club career, he played for the USSR team and the Olympic USSR team and was twice included in the list of the “33 best footballers” of the country.

In 1968, Lobanovsky started his career as a coach. The 29-year-old coach took up a premier league club, Dnipro Dnipropetrovsk and led it to the major league where the team at once rated the sixth in the very first championship. In October 1973, Lobanovsky was invited to Kyiv where he headed Dynamo. He became the most titled coach in the history of the Soviet football for his team won the UEFA Cup Winners’ Cup twice and won the European Cup. The evidence of the master’s talent and qualification are not only the results but also the players he educated. Oleh Blokhin, Ihor Bielanov and Andrii Shevchenko received the Golden Ball (the prize given the best European’s footballers) in 1975, 1986 and 2004 respectively.

Lobanovsky headed the USSR team in different years. In 1967, it won the bronze medals at the Olympic Games and was runner-up at the European Championship. Lobanovsky also trained foreign teams, the team of the United Arab Emirates and the team of Kuwait. Under his management the team of Kuwait won the bronze at the Asian Games. After he returned to Ukraine, Lobanovsky headed Dynamo Kyiv again and became the head coach of the Ukrainian team in January 1998.

In May 2002, Lobanovsky felt bad during the championship match with Metalurh in Zaporizhia. His illness was diagnosed as a stroke and the coach had an operation, but his heart stopped on May 13. Lobanovsky was buried at the Baikove cemetery. The epitaph reads: “We are alive until people remember us.” The memory about the great coach is not fading. The Dynamo Stadium in Kyiv is named after him. Lobanovsky was posthumously awarded the title “Hero of Ukraine” and the UEFA Ruby Order of Merit for his contribution into the football development.

Newspaper output №:

№42, (2011)Section

Culture