Return without address

The exhibition “I Go and I Come Back. Selected Works from the Hradobank Collection” became another reminder for the lack of a modern art museum in Ukraine

The adventures of the Hradobank collection are, in a sense, a reflection of the modern history of Ukraine. At first there is an easy fortune, sandcastles of patronage and collectorship, built on a shaky foundation of a half-criminal economy; in parallel, there is a feverish bloom of domestic postmodernism, suddenly popular in offices and homes of the nouveau riche; then – the spectacular collapse, as the collection becomes confiscated as a debt payment and gets transferred to the temporary owner (NBU) – which, even though it is a state structure, behaves like a raider; and finally the ellipsis of lawsuits, still ongoing today.

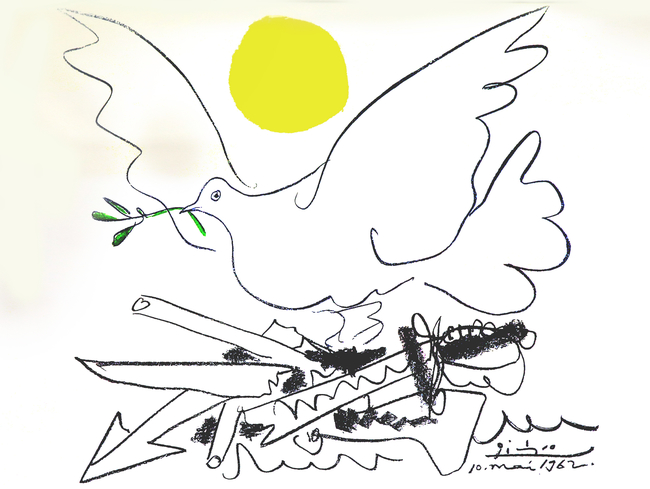

A showy introduction awaits in the first room of the display – a wall decorated with classical European art: Degas, Picasso, Renoir, Chagall, Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Klee, Joan Miro. Those are not original pieces of art, but copies, certified by the rightful holders – but these copies are no less beautiful. Especially memorable are the unexpectedly sentimental Napoleon by Lautrec and The Man by a Cubist Georges Braque – the latter, as it turns out, had had a fluid line, as capricious as one by the rowdy Miro. But meaningful dominant of the collection is of course the Ukrainian Art of the 1980s-1990s.

The selection of paintings, despite their relatively small number (only 10 percent of the collection has been put up for display – which required, however, no less than three rooms) is producing a similarly remarkable analogy to the social conflicts of the early independence. Most of the paintings, again, are coming from our home-grown Ukrainian Postmodern, which had been demonstrated for countless times and still is in NAMU and other places throughout around Kyiv, and which has long expired. The irony has evaporated along with its context, the images, so shocking in the past, now look even more banal than Warhol’s can of Coca-Cola; and the loud struggle against the predecessors, contemporaries, and comrades of the time, looks nowadays as nothing more than a storm in a glass of mineral water, taken at a post-display celebration.

There are some really decent works. The years have not worsened the pictures by Oleksandr Sukholit, Mykola Kryvenko, Lev Markosian, Petro Bevza, and Anatolii Kryvolap. The most important issue is what will happen to the collection from now on. It is important even not in the light of the ongoing litigation – which will hopefully end in favor of the National Art Museum – but in more serious perspective. The issue is that despite the quarter-century-long talks of creating a real, spacious, well equipped, and actively communicating Museum of Modern Art, there has been no real work to implement it. Is it the lack of money, or of the political will, or of social cohesion, or is it everything together – one can argue for a long time, but the result would be the same. The art that will constitute our cultural memory in the future, is now lost in the vaults, private collections at home and abroad. And no one raises a new Maidan on this occasion.

Although sometimes it seems that only that last solution would have helped.

The exhibition will be open through January 15, 2017.

Newspaper output №:

№75, (2016)Section

Time Out