About Grotowski

The Day’s journalist visits the theater where the genius Polish director used to work

The name of Jerzy Grotowski (August 11, 1933 – January 14, 1999, Pontedera, Italy) is more than significant in the world theater. During his lifetime he was named one of the living classics of directorship, and his concept of “poor theater” has revolutionized the scenic art.

Apart from theater education, he was fundamentally educated in the sphere of psychology and Eastern philosophies. All this made the groundwork of his research, which had the only purpose: to obtain the pure energy of theater hidden behind actor’s and director’s cliches, as well as sham luxury of decorations or costumes. An actor is enough for a good show. “Poor theater” meant exactly this thing: nothing should have impeded the emotional contact of the stage and the audience.

The contact was successful. Every play became sensational. The self-devotion of the actors, the depth of their transformation, the space thought out in detail (there were no decorations, an “architect” was working instead of the set designer and completely rebuilt the space of both, the hall and the stage) – all this made Grotowski a symbol of radical scenic innovations. During the last years of his life he worked in Italy mostly as a theater pedagogue. Ukrainian actor Hryhorii Hladii, as well as singer and actress Natalia Polovynka were taught at his center in Pontedera.

One of the most significant episodes in Grotowski’s biography was when he worked as the head of the laboratory theater in Wroclaw in 1965-84. The laboratory showed only three plays, Acropolis (based on Stanislaw Wyspianski’s play), Apocalypsis Cum Figuris (composition from the Bible, works by Dostoevsky, Slowacki, T.S. Eliot, Simone Weil), and The Constant Prince based on the tragedy by Pedro Calderon, but owing to them Wroclaw became one of the world theater capitals.

My situation with Grotowski was weird, because I haven’t seen any of his plays, like those who make a pilgrimage to Opole (where he started his work), Wroclaw, or Pontedera. I entered the history of theater department, Karpenko-Kary Institute, in 1994. At that time Grotowski was perceived as a revelation or an ideal weapon that at that time seemed to be helpful in ruination of the dead stuffiness, filling the Ukrainian theater. The recording of the staged works of the laboratory were one of the greatest shocks. The incredible intensity of the actors’ living through every second on stage. The superhuman level of mastery of the voice and body. The significance of every gesture and sound. The comparison of this level of performance with a nuclear reactor is the best.

Actually, this metaphor was used by a person who brought the tapes with the recordings of the plays to Kyiv, gray-bearded Pole named Bruno Gojak, an archivist from the Grotowski Institute in Wroclaw.

Twenty years later Bruno and I met at the Rynok Square at the historical center of Wroclaw. In the center of the square there is a block of four-storied buildings. In the needed alley we come up to the doors marked with an uneven red spiral, which looks like the letter G. This is an entrance to the Jerzy Grotowski Institute, earlier the Second Studio, even earlier – the theater lab.

In the rebuilt premises where the archives of the Institute are located, and previously “the director’s office was in this corner” (the heart of the theater critic is beating in excitement) Bruno shows the dossier of Ryszard Cieslak, the leading actor of the Laboratory, his work book, and the application for a job in a theater. We go up the stairs, used by the audience to get to the plays, to the same hall, where the brick walls, which have remained red, saw The Constant Prince.

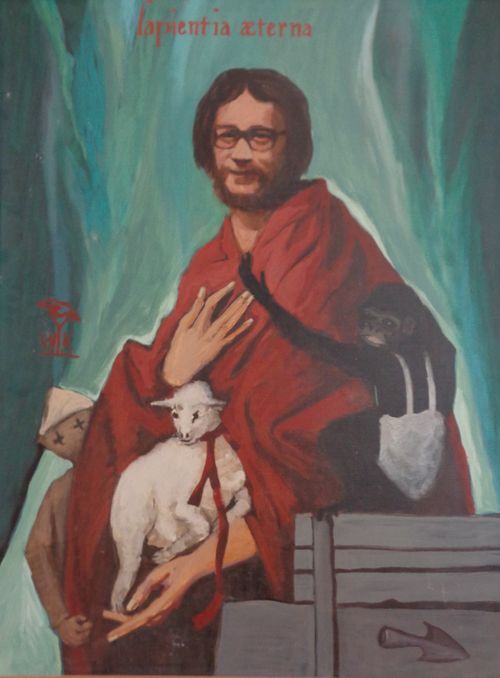

GROTOWSKI IS DEPICTED ON A LIFETIME PORTRAIT IN THE TOGA OF AN ANCIENT SAGE. THE LATIN INSCRIPTION “SAPIENTIA AETERNA” MEANS “ETERNAL WISDOM.” THE PORTRAIT’S AUTHOR WALDEMAR KRIEGER WAS THE ARCHITECT OF ALL THE THEATER-LABORATORY’S PRODUCTIONS, AS GROTOWSKI REJECTED THE TRADITIONAL CONCEPT OF SCENOGRAPHY

We continue our conversation in an office, a middle-size room with book shelves, computers, an original billboard Apocalypsis Cum Figuris, and Grotowski’s lifetime portrait, where the director is depicted wearing a toga of an antique sage.

ANNOUNCEMENT

Bruno, what is your story with Grotowski?

“I come from Lower Silesia, lived in the town Swidnica, there was a military base located in the postwar period. I moved to Wroclaw at the age of 10, in 1963. In school I read in newspapers the news of culture, among other things – the weird reports about the laboratory theater. Second and third years they showed the same plays. Were they talentless? As a boy, I didn’t understand much. But, when I was 18 years old, Grotowski gave an announcement that he needed young employees, held an exam, and hired 10 young people, me in particular, in 1970. I have worked for about a year at his theater.”

Why did you leave?

“I needed to study at a secondary school, after which I worked according to my profession – restoration of monuments. And 20 years later, the so-called Second Studio stopped its activity, the power initiated the establishment of the Grotowski Institute at the place of the theater. They needed an archivist. I offered my candidature and for 25 years have been working here.”

APOCALYPSIS

What do you remember about those plays?

“I remember well the first version of Apocalypsis. All walls are painted in black, the ceiling in white. There were two small lights standing in the corner, they were covered with caps that narrowed the sun rays, directed at the ceiling, and the audience, as they entered the hall, lost the feeling of space: because of the black walls the room seemed bigger than in reality, and the light reflected from the white ceiling, gave an elusive shimmering. Apocalypsis Cum Figuris is a very complicated work. At first Grotowski was going to stage Juliusz Slowacki’s drama Zborowski, the decorations were ready, but he cancelled everything and started to make a play without a text: he invented a physical score, and the texts were brought by actors – fragments from the Bible, Dostoevsky, Simone Weil. The preparation took a total of several years.”

What was the stimulus for him to create this work?

“According to Cieslak, the impetus was the parable about the Great Inquisitor from the Karamazov Brothers. Grotowski told the actors, ‘Imagine a situation: we are living in the world as it is. Then Christ appears. What would people do? Recognize him? How would they behave?’ That was the key question of the play. The following reference was in the groundwork of improvisations: they imagined that a company gathered in a new, still empty flat, they are celebrating the house-warming party, everyone is drunk, and suddenly some tramp was brought into this mess. And they recognize Christ in this tramp. The first words, ‘you were born in Bethlehem, they didn’t recognize you when you arrived’ is the beginning of the play.”

NORMAL CONDITIONS

What was the meaning of the Wroclaw stage for Grotowski?

“He said to himself, ‘Wroclaw is the city which for the first time provided for us, as an ensemble, normal conditions for life and work.’ In Opole there were not enough flats for actors, they were living in the theater. And in Wroclaw everyone had flats or place to live in the actor’s house.”

What were your relations with the authorities?

“The then city mayor, Professor Boleslaw Iwaszkiewicz, when he found out that an interesting theater was functioning in Opole and that it has problems, offered to Grotowski: ‘Go to Wroclaw, we will invent something for you.’”

What about the money?

“There was a Society of Wroclaw Lovers. Money was allotted for them to erect a monument, but it was not erected because of a number of circumstances, a lot of money was left which had to be used – otherwise the budget would have been cut. So, the theater started to function with this Society. Later the City Council signed a status of a laboratory theater: let’s say, it was not a theater, but a special institution on actor’s mastery research – a scholarly institute which shows the results of its research in plays. The theater went a lot on tours abroad. The power put up with it.”

SELF-DESTRUCTION

When Grotowski dissolved the studio and left abroad in 1984, what were his reasons?

“Purely artistic, not political.”

Most of the Laboratory died during the years that followed his departure.

“In fact the reasons for self-destruction were laid earlier. It is no secret that, for example, two leading actors of the laboratory, Cieslak and Stanislaw Szczerski were alcoholics, unfortunately. The cooperation with Grotowski prolonged their artistic and physical life.”

ARCHIVES

What is the institute involved in?

“Historical-archival research, and not only that.”

Do you maintain the relations with contemporary Polish theater?

“Very weak. More with theaters from abroad, a lot of foreign directors and actors come. And there are few Polish students. Our manager is a director; he stages plays. But from the very beginning we are not connected with any theater. The main task is to scholarly process what has been left. At the same time we are holding exhibitions too. We want it to be a place of living art.”

Have you thought about museumification?

“I’m not sure that it would be a good decision to do so. There are few things of museum importance that have been left. There will be a department at the local museum. It would be better if scholars came and used our archives.”

PARADOX

You have said that few people take interest in Grotowski in Poland. Why?

“I don’t know. There is something about Poles. For some reason people here consider that if art is national, it cannot be international. And suddenly an artist who is hardly understood in Poland is understood all over the world. What’s wrong?”

I think it is not a purely Polish problem.

“With Tadeusz Kantor [famous Polish theater director, opponent of Grotowski, who also became famous in the world. – Author] a similar thing happened, he was also blamed for lack of national feeling and patriotism. But he took his play abroad, and everyone saw him as namely a Polish actor.”

RESPECT

What did Grotowski teach you?

“To respect my work. When someone respects what is given to him and what he is doing, then he will respect other people’s work too.”

HAPPINESS

“Do you understand my situation? I don’t feel as a person of theater. I don’t care about theater. My profession is restoration of monuments. Just at some point of time I took much interest with how Grotowski worked. And I was happy to see how he worked.”

The author is thankful to Polish Tourist Organization for their aid in his work on the article

Newspaper output №:

№76, (2015)Section

Culture